Online publication date 27 Feb 2025

Framework to Enhance Critical Information Literacy in University Libraries in Kenya

Abstract

This study investigated adopting a framework to enhance CIL in selected university universities in Kenya. CIL evaluates the effectiveness of Information Literacy (IL), disrupts unfair systems, and creates student-driven IL instruction.

A Descriptive survey research design was used to gather information on a framework to enhance CIL in selected university universities in Kenya. The research was carried out in fourteen university libraries in Kenya. The fourteen university libraries were purposely sampled because they had subscribed to electronic resources and KENET ICT infrastructure and had employed ICT and reference librarians. The target population was 14 University Librarians. The census approach involved all fourteen librarians in this research study. Data was collected on the interview schedule. Atlas. ti was used to analyze qualitative data.

These findings show that university librarians associate CIL with information retrieval. In addition, the findings revealed that the librarians identified key codes of CIL, such as supporting users in access to information, user education, critical thinking, and user information resources. Based on these findings, the study proposes a CIL framework consisting of six steps: Awareness Creation, User needs Assessment and Information Gap, CIL Library Infrastructure, CIL infrastructure, Librarian Empowerment, User Empowerment, and CIL Evaluation.

Keywords:

Access, Critical Information Literacy, CIL frameworks, Critical Librarianship, Metaliteracy, Librarian power, University Library, University Librarian1. Introduction

The libraries have undergone many changes. For instance, libraries have embraced electronic-based information resources such as books and journals. This is according to research by Rafiq et al. (2021), who established that the majority of libraries all over the world have embraced electronic resources. Similarly, research by Mathar (2021) pointed out that physical library building without electronic resources is meaningless or an empty shell. In Kenya, the Commission for High Education (CUE) requires universities to acquire varied, appropriate, and adequate print and electronic information resources (CUE, 2014). In adherence to this guideline, Universities in Kenya must subscribe to electronic resources provided by the Kenya Library and Information Service Consortium (KLISC) (CUE, 2014). This shows that digital resources are rapidly becoming a reality in libraries.

Given these changes, librarians should empower students to access electronic information independently. One way of empowering students is by sharing librarian power with library users (Oyieke, 2015). In academic libraries, sources of user empowerment include online library resources and training/instruction programs. Empowerment equips students with transferable skills that they can use for all types of information retrieval and usage, tasks that enable them to cope with the Information Age. It also gives them the skills to find and use the information they need for school, study, and leisure (Arua et al., 2018). Besides training students, librarians can empower students by acquiring new products, such as remote access tools to enhance access to information resources.

CIL improves IL (Jones-Jang et al., 2021). CIL refers to the ability to evaluate and use information critically (Akayoğlu et al., 2020). A library user can acquire, analyze, and comprehend information to make educated decisions about information access, production, and consumption and take appropriate action (Didiharyono & Qur’ani, 2019). It also includes the awareness of the social and political context in which information is produced and shared and the ability to question dominant narratives and perspectives on libraries and information provision. The purpose of this study was to propose a framework to enhance CIL in selected university universities in Kenya. The following specific objectives guided the paper.

- ⅰ. Assess the librarian’s understanding of the concept of CIL.

- ⅱ. Propose a framework to enhance CIL in selected academic universities in Kenya.

2. Background

Information Literacy (IL) programs should be dynamic and in tandem with library users, library and information resources. The term IL was first used by an American researcher Paul Zurkowski to refer to persons with skills in information areas relevant to their workplace (Landøy et al., 2020). To incorporate the changes in information retrieval, ALA revised the concept of IL as a set of abilities requiring individuals to recognize when information is needed and the ability to locate, evaluate, and use effectively the needed information (ALA, 2016). There are several challenges affecting the implementation of IL in developed countries. Tewell (2018) points out that the significant weakness of the traditional form of IL is that it does not address the social and political concerns of information. A study by Oseghale, (2023) established several barriers affecting IL, such as the absence of technical facilities and competent human resources to implement IL. A related study by (Anmol et al., 2021) revealed that IL instruction is unsuccessful because of a lack of training opportunities, a lack of cooperation between library staff and lecturers, ignorance of the value of IL and lecturers, and learners’ resistance towards IL.

2.1 ACLR and SCONUL IL Frameworks

Professional organisations such as the Association of College & Research Libraries (ACLR), Society of College National and University Libraries (SCONUL), and CUE have developed standards and guidelines that guide the implementation of IL (Willson & Angell, 2017). These standards aim to create uniformity and standardization in the delivery of IL programs. The guidelines also provide clear and measurable objectives that can be used to assess the effectiveness of IL programs (Angelakoglou et al., 2019).

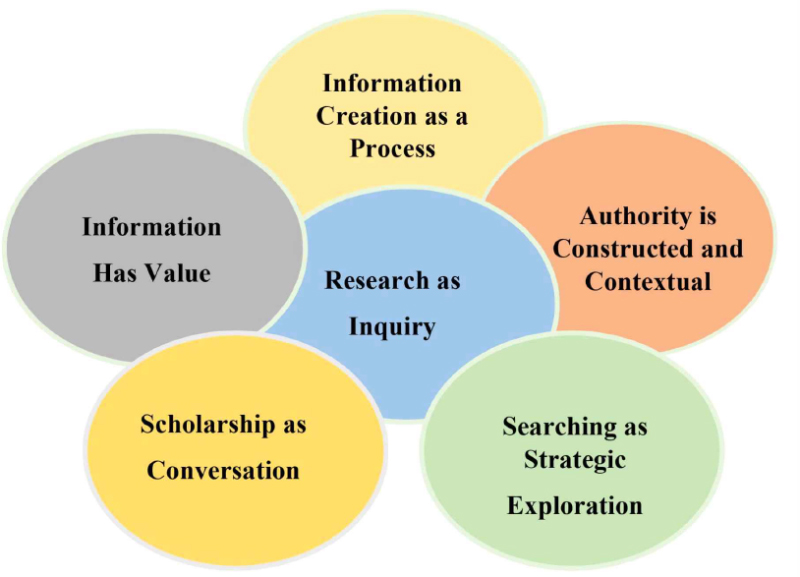

Many Libraries and professional bodies have adopted ACRL policies in delivering IL. For instance, CUE 2014 library guidelines are heavily borrowed from ACRL IL standards (Gross et al., 2022). University libraries in Kenya have further cascaded ACRL guidelines by adopting them into their practices. This shows that ACRL guidelines are essential and relevant in managing IL, providing a comprehensive framework for delivering IL. The following figure 1 shows the ACRL framework.

A study by Fuchs (2022). pointed out that ACRL is a guiding framework designed to help academic libraries in higher education define and assess students’ information literacy skills and competencies. This framework focuses on student-centered learning outcomes and is organised around several core concepts. It includes the following components:

The framework is organised into six frames, each representing a broad concept that shapes the development of information literacy:

- ∙ Authority is Constructed and Contextual: Recognizes that authority is not fixed but is shaped by context and the information needed.

- ∙ Information Creation as a Process: Emphasizes the varied processes behind creating information, highlighting the importance of understanding different formats and methods of creation.

- ∙ Information has Value: This section stresses the ethical and legal considerations of using and sharing information and its value in the academic and broader context.

- ∙ Research as Inquiry: Views research as a process that involves questioning, exploration, and critical thinking.

- ∙ Scholarship is Conversation: Promotes understanding scholarship as a dynamic conversation where ideas are shared, debated, and evolved.

- ∙ Searching as Strategic Exploration: Encourages learners to understand searching as a thoughtful and strategic exploration of information using various tools and strategies.

While the ACRL Framework for Information Literacy is a valuable and flexible tool for promoting critical information literacy skills, its implementation presents challenges related to consistency, faculty engagement, time, assessment, resources, and the preparedness of both students and instructors (Withorn et al., 2021) To overcome these challenges; institutions may need to prioritise collaboration, provide professional development, and build a supportive infrastructure to integrate the framework into teaching and learning practices fully.

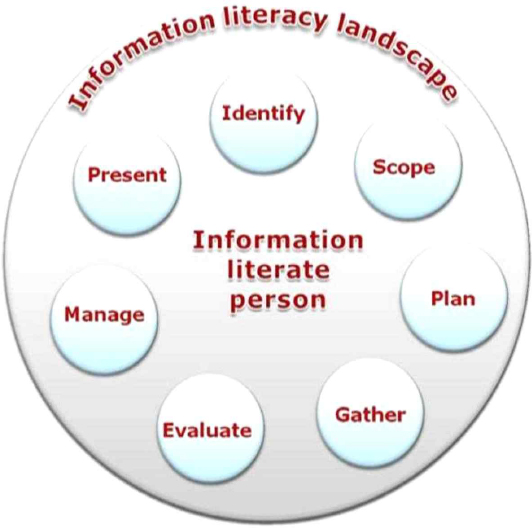

SCONUL also developed seven pillars of IL to provide a comprehensive approach to IL (Hicks & Lloyd, 2021). The seven pillars offer a set of clear and measurable objectives that can be used to guide the development of IL programs (Hicks & Lloyd, 2021). Since then, librarians and educators worldwide have viewed this approach as a tool for imparting their informational abilities to their students (Nakaziba et al., 2022). The SCONUL seven pillars are identify, scope, plan, gather, evaluate, manage, and present information (Encheva, Tammaro, & Kumanova, 2020). The pillars allow individuals and organisations to make informed decisions, solve problems, identify opportunities, and determine the credibility and reliability of their information. Figure 2 shows the SCONUL framework.

Seven Pillars of Information Skills Model (SCONUL)(Source: http://www.sconul.ac.uk/groups/information_literacy/seven_pillars.html)

Each pillar is further described by a series of statements relating to skills/competencies and attitudes/understandings. As researchers become more information literate, they are expected to demonstrate more of the attributes in each pillar and move to the top of the pillar. The names of the pillars can be used to map across to other frameworks for example, the Researcher Development Framework (Vitae, 2010) or to describe part of the research process.

While the SCONUL Seven Pillars of Information Literacy is a foundational and widely recognised framework for information literacy, its weaknesses include a lack of specificity, insufficient focus on critical thinking and digital literacy, limited attention to ethical issues, and challenges with practical application (Alenezi, 2023). For these reasons, institutions may need to adapt and build on the framework to address evolving educational needs, integrate ethical considerations, and incorporate the rapidly changing digital landscape.

The Information Literacy Framework is a set of principles designed to help individuals effectively find, evaluate, and use information (Wegener, 2022). It is primarily used in educational contexts to guide students in becoming more independent, critical, and ethical thinkers. The framework entails several components, such as identifying the information need, finding and accessing information, evaluating information, analysing and synthesizing information, using information ethically and legally, communicating information, and reflecting on the information process Steinerová (2023). The overall goal of the Information Literacy Framework is to equip individuals with the skills to engage effectively with information, critically analyze it, and make informed decisions.

IL framework has several limitations. For instance, IL has emphasised Traditional Research Methods (Taylor, 2021). The IL framework often emphasizes traditional methods of gathering and evaluating information. However, in today’s digital age, much information is accessed through less formal means such as social media, blogs, or crowdsourced platforms. The framework may not always address the complexities of evaluating information from these newer sources. Secondly, it does not thoroughly address the Challenges in Digital Literacy (Ahmad et al., 2021). While the framework promotes evaluating information critically, it does not always sufficiently address the broader skills related to digital literacy, such as navigating algorithms, understanding digital privacy, or engaging with multimedia content. As the internet evolves, these skills are becoming increasingly necessary, and the IL framework might not always prepare individuals for such complexities. Thirdly, the IL framework has an Overgeneralization of Information Needs (Gaillard et al., 2021). The IL framework can sometimes assume that all users have the exact information needs, particularly in academic or formal contexts. In reality, information-seeking behaviour can vary widely based on personal, cultural, or situational factors, and the framework may not fully address the diversity of user needs or contexts. CIL framework will address these gaps by providing a centred approach and inclusion of IT.

2.2 Concept of CIL

A study by Drabinski (2019) acknowledged numerous areas in CIL, namely, redefining the concept of information, identifying and acting upon forms of oppression, recognising and resisting dominant modes of information production, the role of education in social change, empowering student learners, and fighting forms of oppressions. Universities across the world have adopted different definitions and perceptions of IL. Some Universities view IL as a means of accessing information resources, while others view it as long-life education (Landøy et al., 2020). CIL improves IL definitions by capturing information creation, sharing, and power dynamics. For instance, most students are now sharing information via social media platforms. Librarians should also go beyond providing access to information and identify forms of unfairness in Libraries (Barr-Walker & Sharifi, 2019). For instance, librarians should ensure that the catalogs are not biased on some authors. Ultimately, librarians should ensure that students are independent by empowering them with access and retrieval skills.

2.3 Need for CIL

Irving (2018) advocates adopting CIL in libraries by pointing out that access to information alone is inadequate for developing informed library users. CIL is, therefore, established on evolving aspects of IL and is anchored on ACRL guidelines (Haggerty & Scott, 2019). For instance, CIL is anchored on aspects of information, such as power dynamics and information production (Drabinski & Tewell, 2019). CIL addresses how the power system can be used to enhance information access. Libraries should embrace CIL so that users are equipped with access and retrieval skills and the usefulness of information, such as human rights.

CIL acknowledges that libraries are not neutral actors and embraces the potential of libraries as catalysts for social change (Drabinski & Tewell, 2019). This raises some fundamental questions about libraries’ impartiality. Are libraries neutral? Have they ever been neutral? Should they be neutral? Can libraries be neutral as part of societies and systems that are not neutral? Are libraries, through their processes, practices, collections, and technologies, able to be neutral? To answer this question, we must review library practices such as access to library resources. To access library resources, library users need fundamental skills such as CIL and ICT (Sinha, 2024). Unfortunately, many of the students do not possess the requisite CIL skills to access resources (Dashtestani & Hojatpanah, 2022). Besides the skills, the students need the internet and computers to access these resources (Mudra, 2020), for example, when library collections are inadequate, and some users cannot find resources that match their needs (Cheng, Lam, & Chiu, 2020). CIL seeks to correct these imbalances by interrogating the collections.

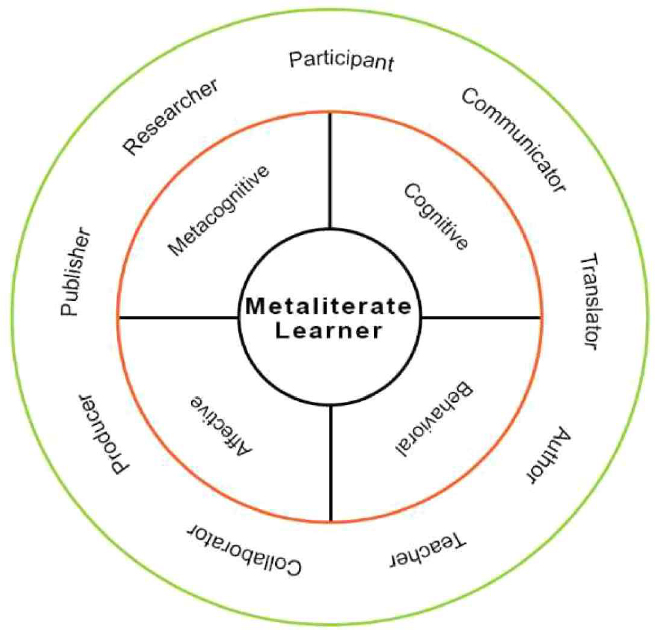

CIL embraces learner-centered methods that involve the students in the learning process (Tewell, 2018). A learner-centred improves the understanding of the concept. Learner-centred methods used in University Libraries are demonstrations and cooperative learning (Ahmed et al., 2022). CIL utilises meta-literacy skills. Metaliteracy is a type of user education that encourages collaboration and critical thinking. It offers a thorough framework for engaging in social media and online communities (Sinha, 2024). According to Mackey (2020), being meta-literate necessitates that people recognise their current literacy skills and areas for development and make decisions about their learning. Metaliterary is further broken down into various literacies such as media, computer literacy, visual literacy, network literacy network, and digital literacy (Statton Thompson et al., 2022). These literacies are essential given that most modern library users in university libraries are young people commonly referred to as the Millennial or X generation (those born from 1982-1995) or the ‘I’ Generation (those born from the mid-1990s to late 2000s). These groups have distinctive characteristics, such as the use of media.

Media literacy is the capacity to retrieve and evaluate information from various sources, such as mass media communication channels (Levitskaya & Fedorov, 2020). It will, therefore, be useful in utilizing different media in the library, such as newspapers and television. Universities in Developed countries have utilised media literacy in other ways. For instance, the University of Northern Texas has uploaded videos on using different information resources and distinguishing fake new resources (University of Northern Texas, 2024).

Metaliteracy is, therefore, an essential way of implementing CIL. Figure 3 below shows the different goals of meta-literacy in promoting access to information resources.

Metaliteracy plays six roles: understanding the content, evaluating information, creating a context, evaluating dynamics, understanding the different types of feedback, and sharing information in a participatory way. It is an all-inclusive ideal that highlights information-related knowledge acquisition while inspiring learners to take control of their learning approaches and objectives (Mackey, 2020).

To attain this inclusive method, the meta-literacy model combines four key aspects: metacognitive, affective, cognitive, and behavioural. Metacognition denotes the processes used to plan, monitor, and assess one’s understanding and performance (Chen, Hsieh, & Liu, 2019). On the other hand, effective learning focuses on how students feel as they learn. Cognitive learning enhances the student’s understanding of the learned concept. Students who have gone through CIL should display new behaviours,s such as the ability to retrieve information. They can better understand new learning material (Post et al., 2019).

The mode of learning in universities has also considerably changed. Universities are quickly adopting online learning as an alternative to face-to-face learning (CUE, 2020). This implies that libraries must redesign the mode of information delivery. This shows that the unprecedented shift brought about by the change of learning mode needed the librarian to apply CIL techniques. The abrupt change from print to electronic caught most users unaware. These scenarios show that users are dependent. They are dependent on libraries, library resources, and librarians. According to Aladeniyi and Owokole (2018), libraries are recognised as the primary learning centres if their resources are well utilised and librarians actively promote access.

The role of the librarian has dramatically changed. According to (Weaver & Appleton, 2020), several approaches exist to provide information. Online learning implies that the students will not be physically in campus and will be self-reliant. A face-to-face student enjoys support from the librarian, can borrow and return books, and enjoys the other library services. Providing services to virtual students implies empowering them to access information independently. Access to information requires creativity, and librarians must employ creativity when discharging library services (Ariole & Okorafor, 2018). For instance, librarians can use virtual means to train users outside the university. Librarians can also use creative methods to promote library resources such as sports and games. Librarians should therefore be transformative and empowering to their services and the users. Librarians also support information production by providing research information, enhancing the visibility of research output, developing and hosting channels, intellectual property management support, editorial support, preserving research output, and repackaging research output to meet the needs of the potential users (Barfi & Sackey, 2021). Ultimately, librarians should employ CIL to address the issues of access to information resources (Mwinyimbegu, 2019). Therefore, CIL is essential in modern times as it encourages librarians to redevelop and reshape their skills continually. CIL approaches benefit librarians in response to issues including pandemics, changes in information formats, and even changes in user characteristics. This study investigated CIL approaches and how they can improve students’ access to information resources in selected university libraries and provide a framework.

Developed countries have approached the implementation of Critical Information Literacy (CIL) frameworks through various initiatives, including educational reforms, public campaigns, and institutional efforts. For instance, In the United States, academic institutions at all levels (from elementary to higher education) have integrated information literacy into their curricula. A study by (Omar, 2024) revealed that the Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL) offers guidelines for implementing information literacy programs that focus on critical thinking, evaluating sources, and understanding the ethical use of information technology. Another study by (Taylor, 2021) established that In the United Kingdom, universities and schools often offer information literacy courses that emphasize the ability to assess digital information critically. Canada has adopted information literacy as a key element of its educational goals, mainly through the Canadian Federation of Library Associations (CFLA), which has worked to create a national framework to guide K-12 and postsecondary education. (Zerkee, 2021). These initiatives show that Developed countries have approached the implementation of Critical Information Literacy (CIL) frameworks through various initiatives, including educational reforms, public campaigns, and institutional efforts. The CIL framework emphasizes the need for individuals to critically analyse, evaluate, and use information effectively in a digital age. This is especially relevant in an era marked by misinformation, disinformation, and the overabundance of information.

3. Methodology

This section discusses the methodology for this study. It presents the following aspects of methodology: introduction, research approach, study population, data collection, piloting, data analysis techniques, research reliability/validity, limitations, and Ethical considerations.

3.1 Response Rate

All fourteen university librarians honored the interview schedules, translating to a 100 % response rate. According to Radez et al. (2021), a response rate of over 75 percent is satisfactory for obtaining objective results in any study.

3.2 Profile of the University Librarians

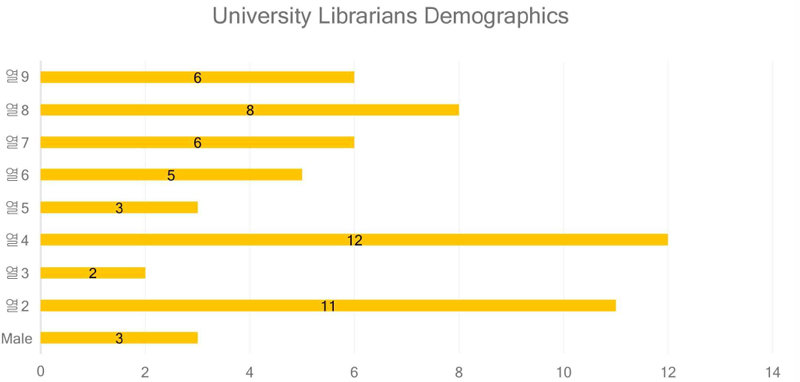

The researcher factored in variables such as gender, highest qualification, and university librarians’ experience to understand library management’s features. This information is summarised in Figure 4.

Figure 4 shows that out of the 14 University Librarians interviewed, 8 (57%) had master’s degrees, while 6 (43%) had PhD degrees. The response on the age was as follows: majority of University Librarians, 6 (43%), had over 50 years, 5 (36%) were between 41-50 years, while 3 (21%) were between 31-41 years. On experience, 12 (86%) University Librarians had served more than ten years, while 2 (14%) had served less than five years. Lastly, regarding gender, the study established that the majority were female 11 (79%). The male librarians were 3 (21%). These results revealed the resondents were mature, gender balanced and had the preliquisite education and expeorince on CIL. These results revealed the respondents were mature, gender-balanced, and had the prerequisite education and experience on CIL.

3.3 Research approach

The researcher used a descriptive survey research design to gather information on the concept of CIL and the CIL framework in university libraries in Kenya. This design was the most suitable for this study because it aimed to establish University Librarians’ opinions about the CIL concept and framework. The descriptive survey research design enabled the researcher to describe the variables under study and derive multiple regressions to predict the dependent variable’s outcome based on the study’s variables (Siedlecki, 2020).

3.4 Target Population

This refers to a group of people or things under investigation and to which the study findings will be generalized (Salari et al., 2020). The target population was 14 University Librarians.

The researcher used the information on the status of the universities and student enrollment provided by CUE publications, Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS), and inclusion and exclusion criteria to determine the number of universities and students involved in this study. The Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria details were subscription to electronic information resources, ICT Infrastructure engagement of ICT, and Reference Librarians. Electronic resources are critical components in delivering CIL, given the emphasis that libraries should adopt digital resources. In addition, Reference and ICT Librarians are integral components of a library. They support students in accessing information resources, which are critical elements of CIL. The selected University Libraries were Egerton University, University of Nairobi, Kenya Methodist University, Technical University of Kenya, Kenya Highlands Evangelical University, Kabianga University, Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology, Rongo University, Tharaka, Meru University, Karatina University, Kisii University, Chuka and Masai Mara University.

3.5 Sampling method and sample size

The researcher used a census approach to involve all the university librarians in this research study. This was because the number of librarians was manageable and would therefore be adequately studied within the limitations of this research study. Sample size refers to selecting a limited quantity of something that is intended to be similar and represents a more significant amount of thing(s) (Mchopa, 2021). The researcher adopted a census approach to involve all 14 respondents in this study.

3.6 Research Instruments and Methods of Data Collection

The researcher used interview schedules to collect data from fourteen university librarians. An interview schedule facilitates data collection to meet specific objectives and helps standardise the interview situation (Sekaran, 2010). One key merit of the interview was the open-ended questions that gave the respondents room to express their opinions.

3.7 Piloting

The pilot study was conducted at Moi University. Moi University met the inclusion criteria but was not sampled for the study. Piloting the research instruments provided data that can ascertain the validity and reliability of the data generated by the tool. The pilot revealed vague questions, creating room for revision. Piloting also provided feedback on the effectiveness of the research questions. Feedback from the pilot study was used to improve the tools and determine the duration of the interview session.

3.8 Data Analysis Techniques

Atlas.ti was used to analyse qualitative data. The audio-recorded interviews collected for the study were thematically transcribed, analysed and classified as guided by the research objectives. The researcher used percent inter-coder reliability. It involves counting the number of times the coders agree on the coded data and dividing it by the total number of coding (Halpin, 2024). This is the most straightforward and intuitive method to calculate inter-coder reliability by determining the average degree of agreement among coders.

3.9 Research Reliability and Validity

Validity is the degree to which questionnaires and interview schedules measure appropriate elements in research (Anderson et al., 2022). In this research, a content validity technique was used to ensure that research instruments have relevant and appropriate content for the study. To achieve this, two specialists in the field reviewed independently the significance of each item in the interview schedule as per the purpose of the study. The researcher corrected the research instruments.

Reliability measures the degree to which the research instrument yields consistent results or data after repeated trials. At the same time, validity is the degree to which results obtained from the analysis of the data represent phenomena under study (Nha, 2021). The research instruments were administered at Moi University before the actual study data collection. The main objective of the pilot study was to pre-test the adequacy of the research instrument. Emphasis was put on the suitability of procedures, sample size, questionnaire demand and responses of each respondent, completeness and variety of information obtained.

3.10 Limitations

The researcher was restricted to fourteen Universities in Kenya. To address this, the researcher used inclusion and exclusion criteria to ensure that the universities selected represent all universities in Kenya.

The other limitation was the tedious protocol of collecting information from the students and library staff. The researcher solved this limitation by using a consent form to assure respondents’ confidentiality. Informed consent allowed the respondents to volunteer their participation freely, without threat or undue coaching. In addition, the researcher faced the limitation of obtaining ethical approval from the relevant authorities to conduct the research in the universities. This limitation was addressed by initiating requests for approvals on time.

3.11 Ethical Considerations

First, the researcher submitted a written request for permission to commence a data collection process from the School of Graduate and Advanced Studies (SGAS) at the Technical University of Kenya (TUK). The second step involved obtaining clearance from Accredited Institutional Ethics Review Committees (IERCs) at Chuka University; thirdly, the researcher sought permission to collect data from the National Commission for Science, Technology and Innovation (NACOSTI), which issued a research permit on behalf of the Government of Kenya (GoK). Last, the researcher obtained permission from the selected public universities to collect data.

The researcher also ensured the respondents were not harmed or exposed to risk. To achieve this, the researcher requested respondents to complete the consent form in Appendix II to seek consent from respondents. The consent form also explained the purpose of the study and the terms of their participation, such as their right to confidentiality and anonymity, as well as their right to withdraw from research. The consent form also permitted the researcher to use or share data from the respondents. The researcher also steered clear of dishonest tactics when conducting the study. The researcher also secured the data by passwording the computers with data.

4. Findings

The findings of this study are presented according to its objectives. The following section presents the findings.

4.1 General Understanding of CIL in Selected University Libraries

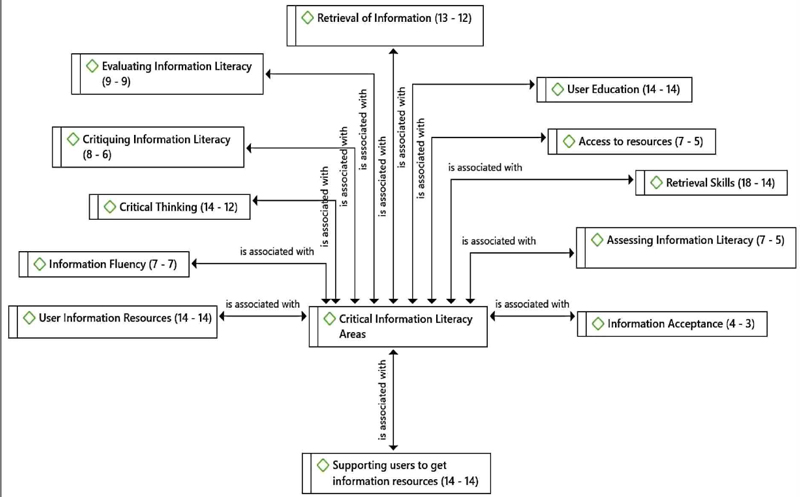

This section presents qualitative data from University Librarians who were asked to explain their understanding of CIL in university libraries. The qualitative data was analysed using Atlas.ti software. A codebook was prepared, and 14 codes were identified. The MS Word transcripts containing the qualitative data were fed into the Atlas.ti software, which provided the data presented in Figure 4. The codes on the concept of CIL approaches are presented in Figure 5, which shows a network view of 14 codes.

The network diagrams produced by Atlas.ti revealed the relationship listed below:

“Is associated with”: This link category can show that two codes are related in some way but not mutually exclusive. For example, you might connect the codes “librarian” and “access to information resources by students” using an “associated with” link. This link would indicate that librarians often facilitate students’ access to information resources.

Figure 5 is a network view of the General understanding of CIL approaches showing 14 codes from the data and their respective relations.

Table 1 is a summary of network view of the General understanding of CIL approaches.

The highest response on general understanding of CIL was retrieval skills, as revealed by the value 18. This was closely followed by assisting users in getting information, user education, critical thinking, and user information resources, as shown by the value 14. There were thirteen responses regarding the retrieval of information. The codes on evaluating information literacy, assessing information literacy, information fluency and access to resources received 9, 7 and 6 responses, respectively. Similarly, there were four responses about critiquing information literacy and information acceptance.

Some of the verbatim responses from the respondents were:

“Critical Information Literacy involves the assessment of information literacy programs to unmask their strengths and weaknesses. This is done to evaluate the effectiveness of IL programs. For instance, after every IL session, trainees are required to fill out an evaluation form on several aspects of IL, such as the effectiveness of the resources and methods used.” [University Librarian 1]

“CIL entails helping users in downloading information from different sources. The information in the library is organized in several databases such as Springer and Elsevier. CIL equips users with skills on how to retrieve information from various databases.” [Librarian 5]

“CIL questions the relevance and value of IL. For instance, most of the librarians offer Communication Skills sessions through lecture methods. Use of communication Skills approach has several limitations such as large classes. CIL examines such limitations and suggests better ways of offering CIL with the aim of providing better approaches to CIL.” [Librarian 6]

“I love equipping my students with hands-on skills on how to access information on their own. One of the best ways to do this is by using practical examples. I sample some of the assignments the students have been given by their lecturers. I then engage the students in identifying the best resources for that assignment. I then look at the students and evaluate the assignments. This way, the students develop Information Competence as opposed to Information Literacy.” [Librarian 8]

“CIL is about Use of Information. Teaching access to information is not enough. The students should be taught how to use information resources. This is critical because some of the students copy the textbooks word to word when doing the assignment. The students should be guided on paraphrasing and summarizing skills. More so, the students should develop responsible use of information skills where the cites acknowledge information used.” [Librarian 14]

4.2 Framework to Enhance Critical Information Literacy in University Libraries in Kenya

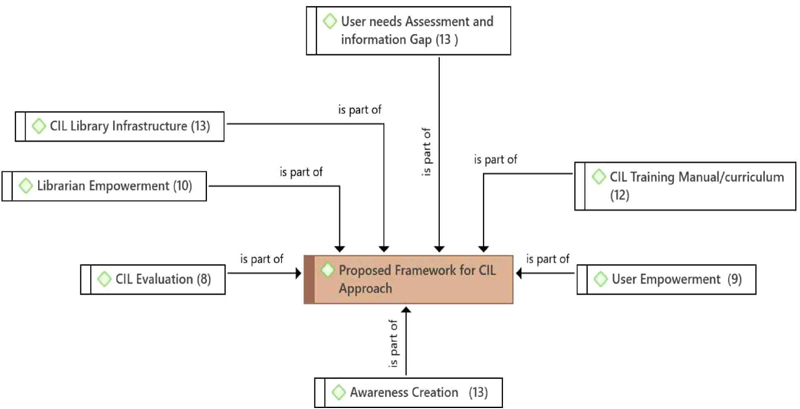

Figure 6 presents the codes for the CIL approach concept. It shows a network view of 14 codes.

Table 2 is a summary on the Proposed Framework for Critical Information Literacy

The highest response on the proposed framework on CIL was awareness creation, user needs assessment, and CIL infrastructure by the value 13. This was closely followed by CIL training manual, curriculum, and Librarian empowerment, as revealed by codes 12 and 10. There were nine responses to user empowerment.

Some of the verbatim responses from the respondents were:

“Most of the Librarians do not understand the concept of Critical Information Literacy. The first step, therefore, should be sensitising librarians to the concept of CIL. Awareness will enlighten staff members to appreciate the value and role of CIL.” [University Librarian 1]

“CIL requires several resources such as computer, internet and seminar rooms. Unfortunately, these resources are missing in many public universities. University Management should lobby for adequate budgets to ensure that this is addressed.” [Librarian 5]

“Successful implementation of CIL requires a curriculum. For instance, most librarians offer communication skills sessions through lecture methods. Use of communication Skills approach has several limitations such as large classes. CIL examines such limitations and suggests better ways of offering CIL with the aim of providing better approaches to CIL.” [Librarian 6]

5. Discussions

The following subsection presents discussions of this study. It covers the concept of CIL and the proposed CIL framework.

5.1 Concept of CIL

To better understand CIL approaches, it is fundamental to understand their meaning and importance. The findings from university librarians (see Figure 6) provide several codes used to describe the CIL concept. The code with the highest response on a general understanding of CIL was ‘retrieval skills’. The second highest codes were ‘assisting users’, ‘user education’, ‘critical thinking’ and ‘user information resources’. A study by Didiharyono and Qur’ani (2019) pointed out that CIL is the library user’s capacity to acquire, analyse, and comprehend information to make educated decisions about information access, production, and consumption and to take appropriate action. CIL issues affecting information access, including forms of oppression, awareness of social and political contexts of information production, and even questioning dominant information access practices, were not expressed. A study by (Drabinski, 2019) identified these CIL issues discussed above, identified and rethought ways of acting upon these forms of oppression, and empowered students through understanding the CIL concept.

These findings show that the university librarians associate CIL with ‘retrieval of information’. In addition, the findings revealed that the librarians identified key codes of CIL such as ‘supporting users in access to information’, ‘user education’, ‘critical thinking’ and ‘user ‘information resources’. A study by Akayoğlu et al. (2020) pointed out that CIL is the ability to evaluate and use information critically. Another survey by Martínez-Ávila and Cuevas-Cerveró (2022) summarised CIL as a broad vision with the following features: critical thinking, information as a social construct, recognition the need for librarians, recognition of students as information users with their own experiences and emphasises that information literacy is meaningless without purpose and action.

The findings show a consensus on the definition of CIL among university librarians. In general, CIL in the current context could be termed as improving IL, evaluating IL, training students on how to access information resources, and providing guidance, support or assistance given by libraries to enable students to access information resources. These views of librarians on the concept of CIL provided the foundations of the CIL framework. The CIL framework is presented in the following section.

5.2 CIL Framework

The findings from university librarians (see Figure 6) provide several codes that are part of the CIL framework. The findings from university librarians (see Figure 6) provide several codes on the CIL framework Awareness Creation, User needs Assessment and information and CIL Library Infrastructure. The second highest codes were CIL Training Manual/curriculum, Librarian Empowerment and User. Momanyi et al. (2024) pointed out that most of the librarians in Kenya are not conversant with the concept of Critical Information Literacy. A study by Park et al. (2020) revealed that user awareness is essential to Critical Information Literacy. A survey by Hicks (2021) identified the curriculum as a necessary resource in the framework of Critical Information Literacy.

The findings show a consensus among university librarians on the CIL framework. In general, the CIL framework entails Awareness Creation, User needs Assessment and information, and User Empowerment. Librarians’ views on the CIL framework provided the foundations. The CIL framework is presented in the following section.

The framework was developed with input from Librarians’ interview responses, CUE standards and guidelines on university libraries, and the ACRL and SCONUL Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education. Integrating the framework with CUE, SCONUL, and the ACRL framework will result in a more comprehensive and integrated approach to CIL. This approach could help students develop self-efficacy to access information resources independently.

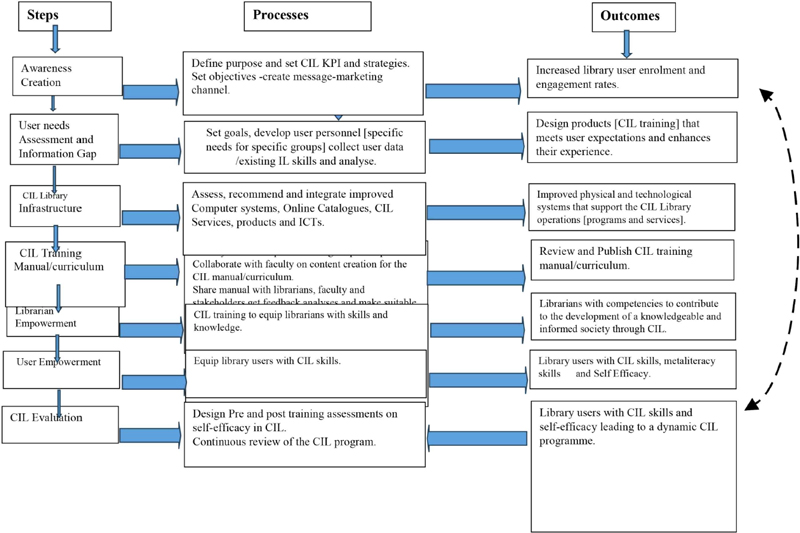

The proposed framework would enhance students’ access to information resources by providing practical skills for information access. By integrating the ACRL framework into the CIL, students can better understand how to identify, access and evaluate information sources. This will help students to acquire, analyse, and comprehend information in order to make educated decisions about information access, production, and consumption and to take appropriate action. The following section presents the framework for CIL approach access to information resources by students in University Libraries. The proposed CIL framework is shown in Figure 2.

The first step in using CIL approaches in access to information resources by students in University Libraries in Kenya involve awareness creation. This step aims to create awareness amongst students and library staff on CIL issues, such as the concept, elements and benefits of CIL (See section 1). This step will involve several activities, such as defining the purpose and setting CIL Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) and strategies. University librarians will carry out this step through channels such as consultative meetings, the circulation of information on CIL through emails, training, social media, and the posting of information on library websites. The outcomes of this process will be increased library user enrolment and engagement rates.

The second step in using CIL approaches to access information resources by students in University Libraries in Kenya involves user needs assessment and information gap analysis. The key processes in this step entail setting goals, developing user personnel (specific needs for specific groups), collecting user data/existing IL skills, and analysing.

During user needs assessment, the librarian will use their power to identify gaps and improve CIL resources and methods. In addition, librarian power can enhance ‘students’ technical skills, meet user needs, provide information retrieval tools, and control access to information and knowledge. This step will lead to several outcomes, such as designing products [CIL training] that meet user expectations and enhance their experience.

The third step in the process of using CIL approaches to access information resources by students in University Libraries in Kenya is CIL Library Infrastructure. CIL Library Infrastructure entails improved resources and services that support the implementation of CIL. This stage will entail several processes, such as assessing, recommending and integrating improved computer systems, Online Catalogues, CIL Services, products and ICTs. The key outcome of this step will be improved physical and technological systems that support the CIL Library operations programs and services. This step emphasises the need for relevant infrastructure that supports access to information resources. The outcomes of this step are improved physical and technological systems that support the CIL Library operations [programs and services].

This is the fourth step in this framework. The key processes in this stage will be identifying and developing the CIL training scope and policies, collaborating with faculty on content creation for the CIL manual/curriculum, and sharing the manual with librarians, faculty, and stakeholders to get feedback analyses and make suitable changes. The key outcome in this step will be reviewing and publishing the CIL training manual/curriculum.

The fifth step is librarian empowerment. The key process in this step will be CIL training to equip librarians with skills and knowledge. This step will lead to having librarians with CIL competencies that help them contribute to the development of a knowledgeable and informed society. Librarians’ support in accessing and using information resources makes them an excellent university asset. Their competence will guarantee user success in accessing and usage of information resources. Training and development of these librarians should be prioritised to remain relevant and support access to information resources. The outcomes of this process are enhanced professional skills and increased quality in the delivery of CIL.

The sixth step in using CIL approaches to access information resources by University Libraries in Kenya students is user empowerment. The key activity in this process is equipping library users with CIL skills. User empowerment can mean enabling users to do something they previously could not do (and not easily do). It also means giving library users adequate skills to control and direct their academic lives, hence self-efficacy. Self-efficacy leads to students’ self-reliance, confidence and responsiveness to changes, such as virtual access to electronic resources and even virtual learning. The key outcomes of this process will be library users with CIL skills, meta-literacy skills and self-efficacy.

The seventh step in using CIL approaches to access information resources by students in University Libraries in Kenya involves CIL Evaluation. This step will entail two key methods: designing pre-and post-training assessments on self-efficacy in CIL and continuous review of the CIL program. The evaluation aims to assess the completeness/totality of CIL approaches. The outcome of this process will be to provide evidence of library user CIL skills and self-efficacy and any shortcomings. This step will lead to a dynamic CIL programme.

6. Conclusion

This study aimed to assess the librarian’s understanding of the concept of CIL and Propose a framework to enhance CIL in selected academic universities in Kenya. The study established that CIL is in university libraries. It was found that CIL is not a new concept to librarians as they used terms such as retrieval skills, assisting users in getting information, user education, critical thinking, and information fluency. In defining the concept of CIL, the feature of bringing radical change to IL was not prominent. The librarians praised CIL as a survival strategy for access to information resources, especially in the era of the changing information landscape. The study also suggested that the CIL framework entails key steps such as awareness creation, user needs assessment and information gap, CIL library infrastructure, CIL training manual/curriculum, librarian empowerment, and user empowerment. This framework will enhance the use of CIL approaches by students in selected university libraries in access to information resources.

7. Recommendations

This section gives recommendations for policy, practice, theory and further research.

7.1 Recommendations for Policy

- a. The study recommends developing national guidelines for CIL approaches and drawing principles for implementing them.

- b. The study recommends that University and ICT/Reference librarians aggressively promote and market CIL resources through training and sensitisation. They should also use library websites, social media tools, library open days, and bulletin boards to explain the benefits of CIL in access to information resources.

- c. The study recommends improving CIL resources. For instance, OPAC could be made simple and interactive by leveraging modern ICT applications. The study found that OPAC and reference resources were not interactive and straightforward.

- d. The study recommends that librarians enhance students’ ICT/meta-literacy skills by working closely with ICT departments to offer basic computer skills training. The course should also incorporate skills such as critical thinking, media, computer literacy, visual literacy, network literacy, and digital literacy.

- e. The study recommends collaboration between the teaching staff and library on advocacy, design, delivery, and evaluation of CIL. The faculty can also train librarians on emerging pedagogies and approaches.

- f. The study recommends redesigning IL curricula to include a CIL focus. Librarians, in consultation with the faculty, could do this.

- g. The study recommends conducting a regular survey on library resources and CIL. Librarians can use social media tools like WhatsApp and X (formerly Twitter) to provide feedback. This will enable them to get feedback and improve library resources.

- h. Universities’ Librarians should support users by holding regular seminars, conferences, and workshops that bring together students and librarians. The librarians can also utilise ICT and social media applications to reach all students.

- i. University Librarians should collaborate with the faculty in developing the CIL training manual/curriculum. These resources would be handy in teaching CIL.

- j. The study highlights the need for further research to explore the underlying mechanisms through which CIL approaches affect academic performance, including cognitive processes such as critical thinking and problem-solving.

7.2 Practical Implication of the Study

The study suggests the need to develop national guidelines for CIL approaches, drawing principles for implementing them. The analysis indicates the need for future studies on methods for assessing changes in students’ CIL or academic performance afterwards. The study suggests incorporating CIL into the Competency Based Curriculum (CBC).

The study suggests that a Critical Information Literacy approach can enhance access to information resources in university libraries. The findings can inform the development of critical information literacy resources and methods and programs that promote equity and inclusivity in access to information resources. Other libraries, such as special and public ones, can adopt and improve these resources and techniques to increase access to information resources. This study can also lead to maximum utilisation of information resources, enhanced staff productivity and better outcomes and can help organisations make informed decisions about information resources. The study can create awareness in University Management on how university libraries can improve the adoption of CIL. The study also suggests the need to engage Library and Information Science Professionals and University Students in planning and designing CIL programs. Implications of this research can be conducted through stakeholder engagement. For instance, Kenya Library and Information Consortium KLISC could be used to evaluate the impact of CIL.

Declarations

Ethics approval An Ethical review was not considered necessary in accordance with the Technical University of Kenya’s guidance on ethical research.

Funding

This research work was funded by the researcher.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the assistance of the journal editors, manager, reviwers and Technical University of Kenya.

References

-

Ahmad, F., Nikou, S., Ryan, B., & Cruickshank, P. (2021). Workplace information literacy: Measures and methodological challenges. Journal of Information Literacy, 15(2).

[https://doi.org/10.11645/15.2.2812]

-

Ahmed, M. M., Rahman, A., Hossain, M. K., & Tambi, F. B. (2022). Ensuring learner-centred pedagogy in an open and distance learning environment by applying scaffolding and positive reinforcement. Asian Association of Open Universities Journal, 17(3), 289-304.

[https://doi.org/10.1108/AAOUJ-05-2022-0064]

-

Akayoğlu S., Satar, H. M., Dikilitas, K., Cirit, N. C., & Korkmazgil, S. (2020). Digital literacy practices of Turkish pre-service EFL teachers. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 36(1), 85-97.

[https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.4711]

- ALA. (2016). IL for Higher Education Framework. ALA. http://www.ala.org/acrl/files/issues/infolit/framework.pdf, .

-

Aladeniyi, F. R., & Owokole, T. S. (2018). Utilization of library information resources by undergraduate students of university of medical science ondo, Ondo State, Nigeria. American International Journal of Contemporary Research, 8(4), 92-99.

[https://doi.org/10.30845/aijcr.v8n4p9]

- Alenezi, F. (2023). Information literacy conceptions among medical undergraduate students: A case study of the Faculty of Medicine, Kuwait University (Doctoral dissertation, University of Sheffield).

- American Library Association. (2015, February 9). Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education. Association of College & Research Libraries (ACRL). https://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/ilframework

-

Anderson, R., Taylor, S., Taylor, T., & Virues‐Ortega, J. (2022). Thematic and textual analysis methods for developing social validity questionnaires in applied behavior analysis. Behavioral Interventions, 37(3), 732-753.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/bin.1832]

-

Angelakoglou, K., Nikolopoulos, N., Giourka, P., Svensson, I.-L., Tsarchopoulos, P., Tryferidis, A., & Tzovaras, D. (2019). A Methodological Framework for the Selection of Key Performance Indicators to Assess Smart City Solutions. Smart Cities, 2(2), 269-306.

[https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities2020018]

- Anmol, R., Khan, G., & Muhammad, I. (2021). Information Needs and Seeking Behavior of Faculty Members: A Information Needs and Seeking Behavior of Faculty Members: A Case Study of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa-Pakistan Case Study of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa-Pakistan. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/478908059.pdf

-

Ariole, I. A., & Okorafor, K. (2018). Readiness of librarians in public libraries towards integration of social media tools in library services delivery in south-east Nigeria. Information Impact: Journal of Information and Knowledge Management, 8(3), 116.

[https://doi.org/10.4314/iijikm.v8i3.10]

- Arua, G. N., Ukwuaba, H. O., Eze, C. O., & Ezeanuna, G. (2019). Information Literacies to Transform Societies. Qualitative and Quantitative Methods in Libraries, 8(3), 357-375. http://qqml-journal.net/index.php/qqml/article/view/576

- Barfi, F. K., & Sackey, K. A. (2021). The Role of the Technical Universities’ Librarians in the Generation and Management of Technical Research Data (TRD) to Advance Inventions, Innovation and Commercialization in Ghana. Library Philosophy and Practice. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/5664?utm_source=digitalcommons.unl.edu%2Flibphilprac%2F5664&utm_medium=PDF&utm_campaign=PDFCoverPages

- Bent, M., Stubbings, R., & SCONUL. (2011, April 18). The SCONUL Seven Pillars of Information Literacy: Core model. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/259341007_The_SCONUL_Seven_Pillars_of_Information_Literacy_Core_model

-

Chen, L., Lu, M., Goda, Y., & Yamada, M. (2019). Design of learning analytics dashboard supporting metacognition. 16th International Conference on Cognition and Exploratory Learning in the Digital Age, CELDA 2019, November, 175-182.

[https://doi.org/10.33965/celda2019_201911l022]

-

Cheng, W. W. H., Lam, E. T. H., & Chiu, D. K. W. (2020). Social media as a platform in academic library marketing: A comparative study. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 46(5), 102188.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2020.102188]

- Commission for University Education (2014). Commission for University Education - Home. www.cue.or.ke, . https://www.cue.or.ke/

- CUE. (2020). Commission for University Education - Home. www.cue.or.ke, . https://www.cue.or.ke/

-

Dashtestani, R., & Hojatpanah, S. (2022). Digital literacy of EFL students in a junior high school in Iran: voices of teachers, students and Ministry Directors. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 35(4), 635-665.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2020.1744664]

-

Didiharyono, D., & Qur’ani, B. (2019). Increasing community knowledge through the literacy movement. To Maega | Jurnal Pengabdian Masyarakat, 2(1), 17.

[https://doi.org/10.35914/tomaega.v2i1.235]

-

Drabinski, E. (2019). What is Critical About Critical Librarianship? How does access to this work benefit you? Let us know! Art Libraries Journal, 44(2), 49-57.

[https://doi.org/10.1017/alj.2019.3]

-

Drabinski, E., & Tewell, E. (2019). Critical IL. The International Encyclopedia of Media Literacy, 1-4.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118978238.ieml0042]

-

Encheva, M., Tammaro, A. M., & Kumanova, A. (2020). Games to improve student’s IL skills. International Information and Library Review, 52(2), 130-138.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/10572317.2020.1746024]

-

Fuchs, C., & Ball, H. (2022). Making connections for student success: Mapping concept commonalities in the ACRL Framework for Information Literacy, the Common Core State Standards, and the American Association of School Librarians Standards for the 21st-Century Learner. College & Undergraduate Libraries, 28(2), 180-193.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/10691316.2021.1905577]

-

Gaillard, S., Oláh, Z. A., Venmans, S., & Burke, M. (2021). Countering the cognitive, linguistic, and psychological underpinnings behind susceptibility to fake news: A review of current literature with special focus on the role of age and digital literacy. Frontiers in Communication, 6, 661801.

[https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2021.661801]

-

Gross, M., Julien, H., & Latham, D. (2022). Librarian views of the ACRL Framework and the impact of covid-19 on information literacy instruction in community colleges. Library & Information Science Research, 44(2), 101151.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2022.101151]

-

Haggerty, K. C., & Scott, R. E. (2019). Do, or do not, make them think? a usability study of an academic library search box. Journal of Web Librarianship, 13(4), 296-310.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/19322909.2019.1684223]

-

Halpin, S. N. (2024). Inter-coder agreement in qualitative coding: Considerations for its use. American Journal of Qualitative Research, 8(3), 23-43.

[https://doi.org/10.29333/ajqr/14887]

-

Hicks, A., & Lloyd, A. (2021). Deconstructing information literacy discourse: Peeling back the layers in higher education. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 53(4), 559-571.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0961000620966027]

- Irving, C. (2018). Resource centres promoting information access, activism and people’s knowledge. Coady Innovation Series No, 10.

-

Jones-Jang, S. M., Mortensen, T., & Liu, J. (2021). Does media literacy help identification of fake news? Information literacy helps, but other literacies don’t. American behavioral scientist, 65(2), 371-388.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764219869406]

-

Landøy A., Popa D., & Repanovici A. (2020). Collaboration in designing a pedagogical approach in IL. Springer Open. Cham, Switzerland.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-34]

-

Levitskaya, A., & Fedorov, A. (2020). Typology and mechanisms of media manipulation. International Journal of Media and IL, 5(1), 69-78.

[https://doi.org/10.13187/IJMIL.2020.1.69]

-

Mackey, T. P. (2020). Embedding metaliteracy in the design of a post-truth mooc: building communities of trust. Communications in IL, 14(2), 346-361.

[https://doi.org/10.15760/comminfolit.2020.14.2.9]

-

Martínez-Ávila, D., & Cuevas-Cerveró, A. (2022). Critical Information Literacy: An Increasingly Necessary Political Movement. ThinkEPI Yearbook, 16.

[https://doi.org/10.3145/thinkepi.2022.e16a31]

-

Mathar, T., Hijrana, H., Haruddin, H., Akbar, A. K., Irawati, I., & Satriani, S. (2021). The Role of UIN Alauddin Makassar Library in Supporting MBKM Program. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Social and Islamic Studies (SIS).

[https://doi.org/10.24252/literatify.v2i1.23214]

- Mchopa, A. (2021). Research Methods: Qualitative And Quantitative Approaches By: Olive M. Mugenda And Abel G. Mugenda. African Centre For Technology Studies (Acts) Press, Nairobi-Kenya, 2003. Isbn: 9966-41-107-0. 256 pp. Journal of Co-Operative And Business Studies (Jcbs), 5(1).

-

Momanyi, E. M., Ng’eno, E., & Kiplang’at, J. (2024). Enhancing information literacy skills of undergraduate medical students: a curriculum and policy analysis. KLISC Journal of Information Science & Knowledge Management.

[https://doi.org/10.61735/gchda352]

- Mudra, H. (2020). Digital literacy among young learners: How do EFL teachers and learners view its benefits and barriers. Teaching with Technology, 20(3), 3-24.

- Mwinyimbegu, C. (2019). The role of libraries and librarians in promoting access to and use of open educational resources in Tanzania: the case of selected public university libraries. 14(2), 53-68. https://www.ajol.info/index.php/udslj/article/view/203815/192220

-

Nakaziba, S., Kaddu, S., Namuguzi, M., & Mwanzu, A. (2022). Exploring experiences regarding information literacy competencies among nursing students at Aga Khan University, Uganda. Library Management, 44(1/2), 97-110.

[https://doi.org/10.1108/LM-08-2022-0071]

-

Nha, V. T. T. (2021). Understanding Validity and Reliability from Qualitative and Quantitative Research Traditions. VNU Journal of Foreign Studies, 37(3).

[https://doi.org/10.25073/2525-2445/vnufs.4672]

- Omar, A. M., Suleiman, S. M., & Ali, Z. H. (2024). Exploring perspectives and challenges of information professionals in accessing massive open online courses for professional development. Library and Information Science Research E-Journal.

-

Oseghale, O. (2023). Digital information literacy skills and use of electronic resources by humanities graduate students at Kenneth Dike Library, University of Ibadan, Nigeria. Digital Library Perspectives, 39(2), 181-204.

[https://doi.org/10.1108/DLP-09-2022-0071]

- Oyieke, L. I. (2015). New power dynamics in academic libraries: Developing a critical evaluation strategy to improve user satisfaction with web 2.0/3.0 services (Doctoral dissertation, University of Pretoria).

-

Park, H., Kim, H. S., & Park, H. W. (2021). A scientometric study of digital literacy, ICT literacy, information literacy, and media literacy. J. Data Inf. Sci., 6(2), 116-138.

[https://doi.org/10.2478/jdis-2021-0001]

-

Post, L. S., Guo, P., Saab, N., & Admiraal, W. (2019). Effects of remote labs on cognitive, behavioral, and affective learning outcomes in higher education. Computers and Education, 140, 103-596.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019]

-

Radez, J., Reardon, T., Creswell, C., Orchard, F., & Waite, P. (2021). Adolescents’ Perceived Barriers and Facilitators to Seeking and Accessing Professional Help for Anxiety and Depressive disorders: a Qualitative Interview Study. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 31(6).

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-020-01707-0]

-

Rafiq, M., Batool, S. H., Ali, A. F., & Ullah, M. (2021). University libraries response to COVID-19 pandemic: A developing country perspective. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 47(1).

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2020.102280]

-

Salari, N., Hosseinian-Far, A., Jalali, R., Vaisi-Raygani, A., Rasoulpoor, S., Mohammadi, M., ... & Khaledi-Paveh, B. (2020). Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Globalization and health, 16, 1-11.

[https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-020-00589-w]

- Sekaran, U. (2010). Research Methods for business: A skill Building Approach (5th ed.). John Wiley and Sons Publisher.

-

Sharifi, C., & Barr-Walker, J. (2019). Critical librarianship in health sciences libraries: An introduction.

[https://doi.org/10.5195/jmla.2019.620]

-

Siedlecki, S. L. (2020). Understanding descriptive research designs and methods. Clinical Nurse Specialist, 34(1), 8-12.

[https://doi.org/10.1097/NUR.0000000000000493]

-

Sinha, P., & Ugwulebo, J. E. (2024). Digital literacy skills among African library and information science professionals-an exploratory study. Global Knowledge, Memory and Communication, 73(4/5), 521-537.

[https://doi.org/10.1108/GKMC-06-2022-0138]

-

Statton Thompson, D., Beene, S., Greer, K., Wegmann, M., Fullmer, M., Murphy, M., Schumacher, S., & Saulter, T. (2022). A proliferation of images: Trends, obstacles, and opportunities for visual literacy. Journal of Visual Literacy, 41(2), 113-131.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/1051144x.2022.2053819]

- Steinerová, J. (2023). Social and epistemic values of information in the framework of information ethics. Knižničná a informačná veda, 30, 9-38.

- Taylor, N. G., & Jaeger, P. T. (2021). Foundations of information literacy. American Library Association.

-

Tewell, E. (2018). The practice and promise of critical IL: Academic librarians’ involvement in critical library instruction. College and Research Libraries, 79(1), 10-34.

[https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.79.1.10]

- University of North Texas (2024) Fake News - Media and Information Fluency.

- Vitae. (2010). Researcher development framework.

-

Weaver, M., & Appleton, L. (Eds.). (2020). Bold Minds: Library leadership in a time of disruption. Facet Publishing, London.

[https://doi.org/10.29085/9781783304554]

-

Wegener, D. R. (2022). Information literacy: Making asynchronous learning more effective with best practices that include humor. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 48(1), 102482.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2021.102482]

-

Willson, MLIS, MPH, G., & Angell, MLIS, MA, K. (2017). Mapping the Association of College and Research Libraries information literacy framework and nursing professional standards onto an assessment rubric. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 105(2).

[https://doi.org/10.5195/jmla.2017.39]

-

Withorn, T., Eslami, J., Lee, H., Clarke, M., Caffrey, C., Springfield, C., ... & Haas, A. (2021). Library instruction and information literacy 2020. Reference Services Review, 49(3/4), 329-418.

[https://doi.org/10.1108/RSR-07-2021-0046]

-

Zerkee, J., Savage, S., & Campbell, J. (2021). Canada’s Copyright Act Review: Implications for Fair Dealing and Higher Education. Journal of Copyright in Education & Librarianship, 5(1).

[https://doi.org/10.17161/jcel.v5i1.15513]

James Njue Mutegi is the Head Librarian at University of Embu -Kenya. He is also a PhD Student at Technical University of Kenya. His research interest focuses on Access to information, Critical Information Literacy and Information Literacy.

Dr. Lilian I Oyieke is an accomplished academic and practitioner in Library and Information Science. She is a Senior Lecturer in the School of Information and Social Studies. She has a strong background in theory, research and management of information services, resources ICTs and computer software packages (SPSS, ATLAS.ti, IN Magic, Visio, entire MS Office suite, Social Media applications, Blackboard, Question mark, Drupal, HTML, Reference Manager, Endnote). As social institutions seek to build a strengthened framework for information, Lilian’s skills are applicable in various environments. She has supervised several PhD and Master Students. Her technical skills include information policy and strategy formulation, performance evaluation, knowledge management, personal information management, database management, information organization, representation and retrieval, information dissemination platforms, information literacy training, proposal writing, qualitative research methods and mixed methods research design. She has attended and presented papers at academic conferences and published articles in reputable journals.

Dr. Tabitha Mbenge Ndiku is an academic and practitioner in Library and Information Science. She is a Senior Lecturer in the School of Information and Social Studies. She has a strong background in theory, research and management of information services, Tabitha Mbenge Ndiku. Her research interests include disaster management, research methods, marketing public relation and advocacy. She has supervised several PhD and Masters Students. She has attended and presented papers at academic conferences and published articles in reputable journals.