A Balance of Primary and Secondary Values: Exploring a Digital Legacy

This exploratory research explores the concept of a digital legacy as a general concept and as a collection of digital possessions with unique characteristics. The results reported in this article are part of a larger study. In Cushing (2013), the author identified the characteristics of a digital possession. In this study, these characteristics of a digital possession were utilized to explore how the characteristics of several digital possessions could form a collection, or a digital legacy. In addition to being explored as a collection of digital possessions, data was collected about the general concept of a digital legacy. In part I of the study, 23 participants from three age groups were interviewed about their general concept of a digital legacy. Five general characteristics describing a digital legacy were identified. In part II of the study, interview data from Cushing (2013) was used to create statements describing digital possessions. The statements were classified utilizing the archival concept of primary and secondary values, as well as the consumer behavior concepts of self extension to possessions and possession attachment. Primary value refers to the purpose for which the item was created, while secondary value refers to an additional value that the participants can perceive the item to hold, such as a perception that an item can represent one’s identity. Using standard Q method procedure, 48 participants were directed to rank their agreement with 60 statements (written on cards), along a distribution of -5 to +5, according to the characteristics of the digital possession they would most like to maintain for a digital legacy. The ranked statements were analyzed using Q factor analysis, in order to perceive the most common statements associated with maintaining digital possessions for a digital legacy. Q method results suggested that most individuals described the digital possessions they wanted to maintain for a digital legacy using various combinations of characteristics associated with primary and secondary values. This suggests that while some participants will respond to personal archiving based on the concept of preserving identity (a perceived secondary value), this will not appeal to everyone. Information professional could consider this difference in appeal when marketing personal archiving assistance to patrons.

Keywords:

Digital Legacy, Digital Possessions, Personal Digital Collections, Maintaining, Personal Archives, Identity1. Introduction

Nearly two decades ago, Cunningham (1994/1996) wrote of the onslaught of electronic records and suggested that archivists advise creators of digital content on how to maintain their personal collections. He argued that it was in archivists’ best interest to do so, so the digital collections could continue to remain accessible and eventually be accessioned into institutional collections. Cunningham’s suggestion provides scaffolding for the creation of a suite of personal information consulting services for library and archives users that information professionals could offer as a part of public services. However, before this is possible, it is necessary to identify concepts on which to build a foundation for these services. A digital legacy is one concept that could be explored for it’s potential use in the personal information advising service that Cunningham describes.

Archivists utilize the concept of value to identify the material they will preserve for the future. Primary value refers to material that’s value is derived from purposes for which it was originally created, while secondary value refers to value that is based on characteristics and purposes beyond that of which it was originally created. Perceptions of secondary value evolve over time: material that was created for one purpose may be utilized for another purpose years after creation. While this concept of primary and secondary value has mainly been applied in archival appraisal, it may have use for individuals as they identify which digital possessions will constitute a digital legacy.

This study utilizes the concepts of primary and secondary value to investigate the concept of a digital legacy and the desire to maintain digital possessions for a digital legacy. The concept of a digital legacy could be of use to information professionals who might offer guidance to individuals as they attempt to construct a digital legacy.

In the first Stage of Cushing’s study (Cushing, 2013), the author found that individuals could differentiate between personal digital objects using the concept of digital possessions. Personal digital objects that a) provided evidence of the individual, b) represented the individual’s identity, c) were recognized as having value, and d) exhibited a sense of bounded control were characterized as digital possessions. Some participants reported that these digital possessions had greater potential for preservation. Utilizing these findings, the next part of Cushing’s study explored how individuals utilized the concept of digital possessions to conceive of a digital legacy. This article reports the findings of the second part of Cushing’s study, which explored the concept of a digital legacy and how a collection of digital possessions could communicate a digital legacy.

The concept of maintaining a digital legacy was explored as a method of building a collection of personal digital items. Research on collecting behavior has found that individuals construct conceptual boundaries when building a collection. The characteristics that participants’ associated with the digital items they selected to maintain for a digital legacy may serve as the boundaries that individuals use to appraise their personal digital material, which can be useful in future preservation research.

2. Literature review

Several bodies of literature were used to inform this research. Literature that reports on the concept of early intervention with potential donors to archival institutions, as well as studies that utilize the method of early intervention, provided a basis from which to guide the purpose of the study. The concept of personal digital archiving provides evidence of individuals’ needs for preservation guidance. The concept of digital possessions serves as a method with which to differentiate personal digital information that has greater potential for curation and preservation. Studies that explore collecting behavior supply theoretical underpinnings for the building of individual, conceptual boundaries to appraise personal digital material into digital legacy collection.

2.1. Archivists and early intervention with creators of digital content

Examples of archivists offering preservation expertise to potential donors provides one of the most substantial early examples of archivists offering personal information management advice about personal digital materials. However, these examples state that providing this personal preservation advice was motivated by a concern for the stability of digital records that would some day become part of institutional archives holdings.

In his early discussion of the challenges archivists faced in accessioning electronic personal records into institutional archives, Cunningham (1994) suggested that collecting archivists become actively involved in the pre-custodial records creation phase of personal recordkeeping, with the thought that the personal records would some day be accessioned to an institutional archive. By creating an early relationship with the donor/creator and maintaining the relationship over time, the archivist could provide advice to the creator as she managed her collection, leading to a more substantial (potential) donation in the future.

The theme of early intervention was also present in articles that documented viewpoints of archivists recounting their personal experiences working with personal records collections held at archival institutions, and personal observations of archival work. Paquet (2000) chronicled her experiences working with personal records at the national archives of Canada. In recounting, sheexplained that if archivists intervened shortly after records were created, archivists could then have opportunities to educate creators about the necessity of preserving their electronic records. Paquet (2000) discussed her two pronged strategy to address personal records when working with donors, a proactive approach to address recently created records and a passive approach to address records created using older forms of technology that potential donors may not be able to access using current technology.

Thomas developed the Personal Archives Accessible in Digital Media (PARADIGM) project “to explore how archivists might select, acquire, process, store, preserve and provide access to the digital archives of individuals for the use of future researchers” (Thomas, 2007, p. 29). Archivists who worked with the PARADIGM project practiced Cunningham’s (1994/1999) suggested early intervention (Thomas, 2007). The PARADIGM project archivists visited politicians and their staff in political offices to discuss deposit and preservation, as well as to learn which records were most important to the politicians and their staff. The PARADIGM archivists used a survey stage to discover the importance of records. In this survey stage, screen prints or text files of directory lists on all office computers were captured so that the archivists and political staff could begin a dialogue about the digital files (Thomas, 2007). While the project team found the records survey useful, it only provided general information about what existed on a single computer: it did not engage the creator in appraisal and selection of material for preservation.

The Digital Lives project did not explicitly apply Cunningham’s suggestion of early intervention: the project aimed to collect information about the potential of personal digital archival collections for future research, to understand how individuals engaged with personal computers, and to make individuals aware of the necessity of maintaining personal archival collections (John, Rowlands, Williams, & Dean, 2010).

As part of the Digital Lives project, project team members interviewed archivists who work with personal collections (in both analog and digital form) to obtain their views and suggestions on how to maintain personal digital content. The Digital Lives team found that the archivists “wished for instruction manuals” on how to maintain personal digital collections that the archivists could then “enable them to advise in turn the digital public” (John et al., 2010, p. 99-100). These research studies suggest information professionals’ interest in resources that they could employ to help them advise patrons in personal information archiving.

As is evidenced by the body of work, archival scholars recognize the need to provide assistance to creators of digital content, due to the fragile nature of the material. However, this research has yet to identify tangible concepts that archivists could harness to formalize these interactions with creators of digital content that may some day be maintained for the long term.

While not connected to the studies described above, the concepts of primary value and secondary value are well known to archivists and are commonly utilized when appraising archival collections for potential value, before ingesting material into an institutional collection. In Modern Archives: Principles and Techniques (1956) Theodore Schellenberg, “the father of American archival appraisal,” explains that public archives have two different kinds of values: primary value to those from whom they originated and secondary value to other users. Secondary value evolves over time. Archives are typically concerned with collecting material that has a secondary value, while libraries are concerned with collecting material with primary value. For example, the primary value of the United States Census is to determine population figures. Over time, the census has taken on a secondary value for genealogists, who utilize the record to discover information about their ancestors. The concept of primary and secondary value is vital to archivists as they determine value in material, but it also has relevance to individuals as they distinguish digital possessions and determine which digital possessions create a digital legacy.

2.2. The concept of self in the preservation of personal digital collections

Several researchers, many from the human computer interaction (HCI) community, have explored individuals’ maintaining practices of digital material. The common thread in these studies is the concept of self and its influences in the preservation of personal material. The concept of a digital legacy involves these concepts of self.

When describing the personal information management (PIM) meta-level activity of maintaining, Jones (2008) breaks maintaining into several stages, the last stage being “maintaining information for our lives and beyond.” In this stage, individuals maintain digital material that may exist beyond the individual’s life. According to Jones, most personal digital information was maintained for reuse, but personal digital information “for our lives and beyond” suggests that the digital material may be maintained for more than reuse, a concept present in many of the HCI studies described below.

Kaye et al. (2006) conducted site visits, office tours, and semi-structured interviews with 48 scholars at a university in order to understand the personal archiving strategies of academics. Kaye et al. found that academics archived material in order to retrieve it later, to build a legacy, to share information, to preserve important possessions and, to construct identity. These values could effect the design of a personal archive. In addition, the design of the personal archive frequently reflected the creator. Similar to the findings of PARADIGM and the Digital Lives projects, Kaye et al. was also unable to identify any “best practices” for archiving among the scholars, due to the differences in use of tools and individual goals, methods, and styles. Kaye et al.’s finding that individuals archive to construct identity is similar to the archiving values of defining the self, also discussed by Kirk and Sellen (2010).

Kirk and Sellen (2010) found that physical and digital possessions often served as a trace of, or mechanism for, “sacred” things (things regarded with some kind of reverence). Participants imbued the possessions with value because they served as traces of something sacred. Fewer digital possessions than physical or “hybrid” (possessions with physical and digital characteristics) possessions were kept.

The maintained possessions were often removed from functional use. The most common digital items were digital photos and videos. Emails were less popular, but were kept by at least one couple, that kept the emails from when they had first dated. The authors identified six values associated with home archiving, beyond the broad purpose of remembering: defining the self, forgetting, fulfilling duty, framing the family, connecting with the past, and honoring those we care about.

In order to develop new technologies that would enhance individuals’ perceptions of value in their virtual possessions, Odom, Zimerman, and Forlizzi (2011) interviewed 21 teens and tweens (ages 12-17) in their bedrooms, about their material and virtual possessions, as well as had each participant provide a tour of their bedroom.

Odom et. al, found that homework assignments, blog entries, status messages from SMS, archived SMS messages, digital video, digital artwork, digital music and digital photos to exist in participant’s collections. In addition, Odom et al. found several characteristics associated with virtual possessions, including but not limited to

∙ Evidence participants were transitioning to the cloud for file management because of the ubiquitous access the cloud provided;

∙ A desire to move virtual possessions around a digital environment;

∙ An understanding that virtual possessions can represent identity to others; and

∙ A feeling of control over social networking sites, in contrast to their physical location as teens (living in their parents homes)

Odom et. al suggested that a focus on the accrual of metadata, placelessness and presence, and presentation of selves would provide the greatest avenues for design. While not focused on maintaining digital possessions, Odom et al. still discerned findings relevant to maintaining digital possessions.

Concerned with the idea of passing on material and the desire to understand how individuals remember and what they would like to remember about their lives, Petrelli, van den Hoven and Whittaker (2009) directed 10 families to create a time capsule of items that represented themselves that would be viewed 25 years later. The authors found that photographs were the most common item added to the time capsules; possessions once in use and personal belongings were also popular, followed by craftwork, ephemera, and publications. Participants described their chosen items as representing people, the identity of the family, experiences, places, and life today. Petrelli et al. found that the selection process was important, as individuals preferred to reconstruct memories from selected cues rather than from a lifelog that recorded all life events.

Writing from an archival perspective, McKemmish (1996) addresses maintaining behavior from the point of view of institutional archivists who maintain personal collections. Although she did not distinguish between digital and paper collections, McKemmish examined several personal collections of authors. According to McKemmish, evidence of the social uses of personal archival collections can be found in the writings of many popular authors and she examines their writing in her study. Like Kirk and Sellen (2010) and Kaye et al. (2006), McKemmish found that personal archiving served additional purposes beyond the retrieval of items for future use.

The results reported in this article are part of larger study, in which the first stage was reported in Cushing (2013). Cushing (2013) found that individuals could differentiate between personal digital information by using the concept of digital possessions. Cushing applied Belk’s (1988) and Sividas and Machliet’s (1994) concept that individuals can perceive their physical possession to contribute to their identity, to digital possessions to determine what characterized self extended in an digital environment. Furby (1978) identified several characteristics of physical possessions, the most significant being that possessions describe a use, are used to accomplish a means to an end, and are maintained.

Digital possessions are distinguished from all other personal digital material because these digital objects deemed possessionsare characterized as a) providing evidence of the individual, b) representing the individual’s identity, c) recognized as having value, and d) exhibiting a sense of bounded control. One of the larger goals of the study was to explore digital possessions and their implications for maintaining personal information. Part of maintaining personal information is maintaining it in the form of a digital legacy a conceptual collection of related digital possessions. Therefore, it was natural to report these findings in two different articles: Cushing (2013) narrowly focused on digital possessions, while this article focused on the broader perspective of a collection digital possessions, or a digital legacy.

While not specifically reporting findings related to the self or identity, Marshall’s work on personal digital archiving should not be ignored. In the reports of various studies, Marshall (2007/2008a/2008b) and Marshall, Bly and Brun-Cottan (2006) outlined problems and challenges associated with personal digital archiving, or behavior related to maintaining digital material. Marshall and Marshall et al. identified four main attributes, challenges and/or tasks associated with personal digital archiving: digital stewardship/curatorial effort, distributed storage, long term access, and value and accumulation. To ensure long-term survival of digital material, individuals should not ignore collections and let them grow haphazardly, decisions needed be made about what to keep and what to delete. Deciding what to keep was linked with assessments of value at a specific point in time: valuable stuff stayed and stuff of little value was deleted. This made sense in theory, but Marshall et al. (2006) discovered that people put off making value judgments, engaged in spontaneous clean up, and relied upon periodic loss to limit their digital collections. Still, individuals desired a sense of control over their digital belongings. Like curatorial effort, people did not like to make value judgments.

In order to reign in growing individual collections of belongings that may or may not be valuable, Marshall et al. (2006) called for the development of “heuristic notions of value.” These heuristics would be imbedded in personal archiving systems in order to assist people with the cognitive burden of making value judgments. Marshall et al. observed that people expressed value by demonstrated worth, or how often the item was replicated, the creative effort invested in the item’s creation, the time spent creating the item, the item’s stability, and the emotional impact that the item had on them.

Marshall’s research raised an important consideration for the preservation of personal material: that individuals resist engagement in maintaining decisions because the task can be cognitively taxing and time consuming. Therefore, any attempt to work with creators must address the motivation of the creator, and the studies above suggest that identity building and/or display may provide such motivation.

2.3. Theories of collecting behavior

The above studies on working with creators and maintaining behavior suggest that information professionals have a potential role for assisting creators with maintaining their personal digital material. Individuals may be motivated to engage in the cognitively taxing task of maintaining activities related to identity construction and display. Building on Cushing’s (2013) definition of digital possessions, theories of collecting behavior can be applied to collecting digital possessions, which may be of use when working with creators. Like Cushing’s digital possessions, items that an individual considers to be part of a collection are brought together and distinguished from all other items.

According to Rigby and Rigby (1944), collecting has been defined as an “impulse” related to “the instinct to live.” (p. 3-4). A collection has consisted of objects that were selected by the collector and related to each other in someway. A collection should have boundaries. Often, boundaries have been imposed for financial reasons, and so that completion could appear to be attainable (Rigby & Rigby, 1944). Belk (1995) has defined collecting similar to Rigby and Rigby: “the process of actively, selectively and passionately acquiring and possessing things removed from ordinary use and perceived as part of a set of non-identical objects or experiences” (p. 67).

Belk, Wallendorf, and Holbrook (1991) further defined collecting as “a form of acquisition and possession that is selective, active and longitudinal. A necessary condition is that the objects, ideas, beings, or experiences derived larger meaning by their assemblage into a set” (p. 182).

Pearce (1992) has likened collecting to a “non-utilitarian gathering” of related things (p. 50). In addition, collecting involved selection, acquisition, and disposal. Pearce also acknowledged the collector in her definition: a collector should acknowledge a collection as such, and the collector should imbue the collection with a specific value.

According to Pearce (1992), three modes of collecting have existed: “souvenirs,” “fetish objects,” and “systematics.” Souvenirs were related to each other through their relationship with the collector and his life history. A refrigerator magnet collection consisting of refrigerator magnets from each place an individual has visited could be considered a souvenir collection. Fetish objects were objects of desire and were usually rare. A collection of Impressionist art would qualify as a Fetish collection. Lastly, a systematics collection usually consisted of natural history objects and belonged to scientists: these collections helped scientists distinguish between species (Pearce, 1992).

Muensterberger (1994) defined collecting as “the selecting, gathering, and keeping of objects of subjective value” and did not include a statement about boundaries, limits or value (p. 4). Like Belk and Muensterberger, Pearce (1995) agreed that selection was key in the collecting process: “the selection process clearly lies at the heart of collecting” (p. 23). According to Pearce, collecting involved the desire to control and organize, and included “hunting behavior.”

McIntosh and Schmeichel (2004) have defined a collector as an individual “motivated to accumulate a series of similar objects where the instrumental function of the objects was of secondary (or no) concern and the person did not plan to immediately dispose of the objects”; a definition similar to the above definitions of collecting (p. 86).

These definitions of collecting highlight the importance of selection and value, which can be related to constructing a digital legacy. If constructing a digital legacy involves the same boundary building that is involved in collecting, the boundary building may play an important role in the process of selecting which personal digital material to maintain for a digital legacy.

3. Method

This exploration of participants’ definitions of a digital legacy and the characteristics of the digital possessions that constitute a digital legacy was conducted as part of a larger study that explored the characteristics of digital possessions, as well as self extension to possessions in a digital environment, which are reported in Cushing (2013). The main research questions explored by the study reported below relate to 1) how individuals define the concept of a digital legacy and 2) how individuals characterize the digital possessions they would consider maintaining for a digital legacy. Cushing (2013) identified the characteristics of digital possessions. The study described below applies the concept of digital possessions to a digital legacy by exploring digital possessions as a curated collection of material.

The study was conducted in two parts. In Part 1 of the study, participants were interviewed about their definition of a digital legacy in order to understand their definitions of the general concept.

In addition to gain qualitative data about individuals’ definitions of a digital legacy, the data collected from the interviews was used to develop a corpus of statements (Q sample) that would be used for the Q sort tasks.

Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed. Pseudonyms were assigned to all names mentioned by participants in the interviews. The interview data was analyzed using NVivo 8 following the guidelines of Miles and Huberman (1994). Categories of analysis were developed from the interview guide, as well as data that emerged from the semi-structured interviews, and then coded using NVivo.

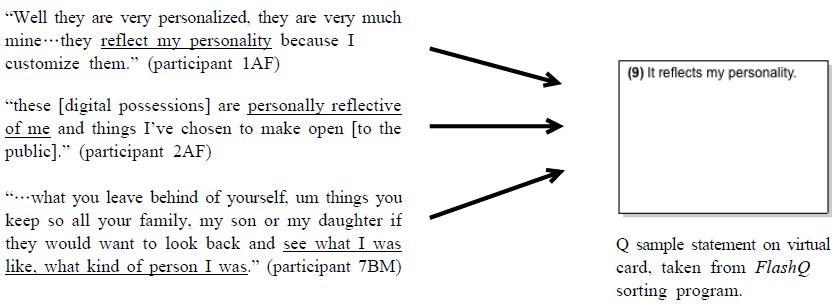

In Part 2 of this study, Q method was used to determine individuals’ opinions about the digital possessions that they would consider to be a part of a digital legacy. Q method utilizes psychometric principles and statistical applications to measure individuals’ points of view about a specific topic. Using standard Q method technique (Mckeown & Thomas, 1988), a set of 60 statements (known as the Q sample) was developed from the most frequently mentioned characteristics during the interviews about the characteristics of digital possessions, as reported in Cushing (2013). Figure 1 displays the process of Q sample creation: several participants mentioned that their digital possessions reflected their personality during the interviews. The validity of the Q method study comes from the development of the Q sample.

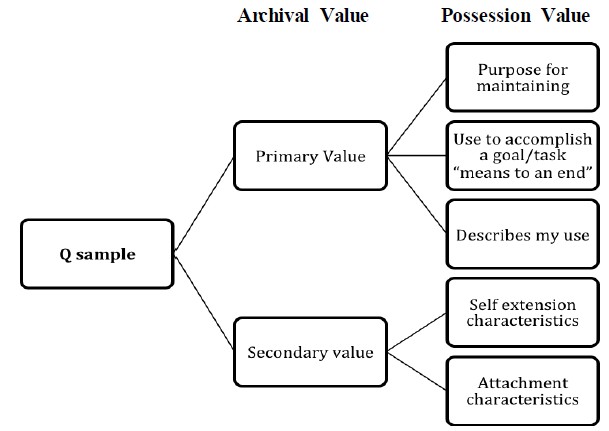

The Q sample was structured according to the concept of archival value, which correspond with- Furby’s (1978) and Belk’s (1988) concepts of possessions (possession level) as a hierarchy to provide structure, which is displayed by Figure 3. As discussed in the literature review, archivists use the concepts of primary and secondary value to appraise material for addition to an archival collection. While the concepts had not been applied previously to personal archiving behavior, these concepts of value were apparent in the characteristics of digital possessions described in the Cushing (2013) interview data that was used to create the Q sample.

Archival value states that items with potential for preservation have a primary value: the item is preserved because of the purpose for which it was created, or a secondary value: the item is preserved because it has taken on a value different from the purpose for which it was originally created (Pearce Moses, 2005). These archival values correlate with the values that Belk (1988)Furby (1978), and Schultz (1989) found to exist when individuals considered their relationships with their physical possessions. Table 2 displays the Q sample statements.

Next, the Part 2 participants were directed to “reflect on the digital item that you most want to maintain for your digital legacy.” These directions to first reflect on a personal digital item allowed participants to rank the statement cards with their own item in mind. This is significant, as it allows the researcher to quantify opinions about the issue at hand relevant across all participants, not the digital item. Opinions about a personal digital item, not an abstract digital item, can be compared.

Once the participant had identified the item, they were instructed to sort the Q sample statements, keeping this item in mind while completing the sort. The “it” to which the Q sample statements refer is each individual participant’s identified digital possession that they would most like to maintain for a digital legacy.

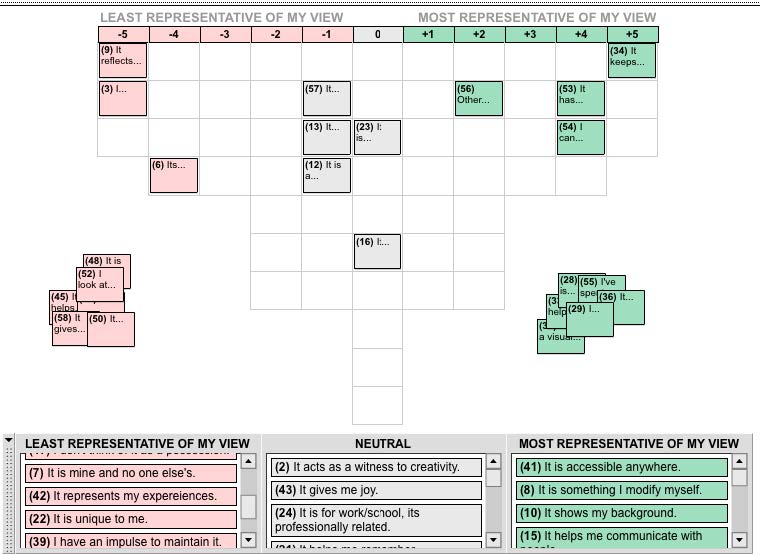

Participants ranked their agreement with the Q sample characteristics statements along a-5 to +5 distribution, in response to directions to sort the [statement] cards according to “least representative of my view” to “most representative of my view.” Figure 2 displays the computer program FlashQ, which participants used to sort the virtual statement cards along the virtual distribution. FlashQ allows the participant to sort the statement cards on a computer screen and automatically recorded the statement scores.

The data was then factor analyzed using the computer program PQMethod, aprogram developed to conduct Q factor analysis. PQMethod produced factors that represented a group of participants who ranked the Q sample similarly, along with the average score of the statements that most represented the factor (Schultz Kleine, Kleine& Allen, 1995). Schlinger’s (1969) formula was to determine significant Factor loadings: 3*1/ √n. Factors were then discussed in detail.

By sorting the statements along the distribution with their selected personal digital possession in mind, the researcher was able to compare individuals’ varying opinions about the characteristics of digital possessions that each individual used to define their personal digital legacy. Q method allowed the researcher to quantitatively measure individuals’ points of view about the concept of a digital legacy and their own items they would like to maintain for a digital legacy. The participant is only prompted to “reflect on the digital item…” so that they can utilize their own frame of reference to explore the concept of maintaining for a digital legacy

3.1. Population

Participants were recruited using a campus wide listserv, posters displayed at various locations in the local area, and word of mouth. Quota sampling, stratified by sex and age, was used to create six sample groups. According to Whittaker and Hirschberg (2001) individuals tend to assess value in their personal collections during periods of transition. Therefore, Levinson’s theory of life stage transitions was used to create the age groups (Levinson, 1990). According to Levinson, individuals experience life stages during several age ranges. The life stages utilized in this study include Early Adult (ages 18-24), Mid Adult (ages 38-47), and Late Adult (ages 58-67). Study Groups A, B, C and D, E, and F correspond to these life stages, as displayed by Table 1. Interview participants were assigned a number, a group letter (A-C) and a gender identified (F or M). For example a participant identified as “2CM ” was assigned the number “2,” was assigned to Age Group “C ” (ages 58-67) and was male, designated by “M.” Participants were not identified by occupation.

4. Findings

4.1. Part 1: Characteristics of a digital legacy

In Part 1 of the study, 23 participants were interviewed in a conference room about their definitions of a digital legacy in order to explore participants’ understandings of the general concept.

When asked to define a digital legacy, most participants reported that they had not heard or used the term in the past. Once the question was posed, some participants began to question what might happen to their digital possessions after they died. One participant in the 18-24 Age Group expressed that thinking about her legacy after death was “morbid,” and something she resisted. Most members of the 58-64 Age Group were more comfortable discussing a legacy after death. Despite unfamiliarity with the term, most participants were able to provide a definition of the term digital legacy. The most commonly expressed characteristics used to describe a digital legacy were that a digital legacy:

∙ displays a progression, tell a story

∙ represents the individual (in a good light)

∙ provides evidence of the individual, usually on the internet

∙ is created or manipulated by the individual

∙ specifically maintained/developed for people other than the individual

An exploration of these characteristics provides a wider understanding of how individuals define a digital legacy and potential uses for the concept.

Several participants clearly expressed that time was a key element in a digital legacy. According to these participants, a digital legacy displayed a progression through time with a beginning, middle (and potential) end. These participants envisioned the digital legacy as an unfolding story of an individual’s life, much like a biography. Participant 1AF described the breadth of a digital legacy:

“I would say a digital legacy comprises of digital possessions that show as start point and progression. Whether that be in a person’s life, or they have digital possessions that kind of pinpoint certain times in their life or whether it shows their growth in a certain area of life as like whatever their talents and skills are whether it be in computers or art or writing or law making, that sort of thing.”

While Participant 1AF was more relaxed with the guidelines of a digital legacy, Participant 3BF was adamant that a digital legacy not only have a beginning and end, but that it also be consistent, without any gaps:

“I think that the idea of a legacy is that there would be um no gaps in it, so I think that it’s, it would be to me, a legacy would be a complete picture as opposed to just intermittent or sporadic pop-ins.”

The beginning and end of the digital legacy had to “look different”, which would demonstrate growth and/or change:

“I guess that’s kind of showing the progression of someone throughout their life I guess through digital possessions, I guess through pictures and whatnot, you can really see how someone changes through these sort of these pictures, through time.” (Participant 4AM)

“Journey”, “picture” and “story” were often used to describe a digital legacy relating to this characteristic. This finding supports Petrelli et al.’s finding that “people want to compare today and the future” when remembering (p. 7).

While most participants agreed that the focus of a digital legacy was a specific individual, several participants further defined the content of a digital legacy by stating that it should represent the individual in a positive aspect. This concept introduces the issue of who has control of a digital legacy, which was previously discussed by McKemmish (1996). Most individuals who stated that a digital legacy should represent an individual in a flattering light also thought that the individual should have the ability to control the creation of the digital legacy, alluding to a collection with boundaries.

It was not uncommon for individuals who discussed this characteristic to state that professional accomplishments should be included in a digital legacy:

“I guess like I would think of um, somebody’s accomplishments being preserved in a digital form so what comes to mind are like um, published papers or something like that” (Participant 5AF).

“I think [a digital legacy] would demonstrate a level of skill, of professionalism…it’s your reputation” (Participant 4BF).

While Participants 5AF and 4BF believed that a digital legacy consisted of accomplishments, participant 4AM wanted to “weed” his digital legacy of evidence of himself that he described as “immature.” McKemmish (1996) reported similar results in her exploration of personal recordkeeping behavior: individuals or the family members of individuals would try to control a legacy by destroying some written evidence of the individual. Other notable figures attempted to control their legacy through the records they were willing to donate to institutional archives. Participant 4AM comments support McKemmish’s (1996) findings:

“I guess the benefit to a digital legacy verses a physical one is that whoever controls the digital files can control what image that digital legacy leaves, and so I feel like things that do not represent me I guess do not represent who I view myself as -I would want to get rid of it.”

Some participants were quick to link a digital legacy with their Internet behavior, specifically postings comments in forums. These participants cautioned that one must curate their digital legacy (or digital footprint) carefully, so that, in Participant’s 2AF’s words, it “doesn’t come back to haunt you.” According to Participant 6BM, his digital legacy consisted of “too many things [he] said on the Internet forums late at night after too many beers.” This finding conflicts with the characteristic that a digital legacy should only reflect an individual’s positive qualities, which again raises the issue of control. While participants who spoke of a digital legacy as evidence of their behavior that was publically available on the Internet were conscious how the behavior may “come back to haunt them,” they accepted this lack of control as a reality of the digital age. While the desire existed to control one’s “digital footprint,” participants accepted the bounded control the digital environment provided, which was also discussed by Cushing (2013) as a characteristic of digital possessions. Whether positive or negative, almost all individuals agreed that a digital legacy was public:

“I would tie it to the Internet a lot-I think, and so it’s just kind of the um, the sum of everything that is directly traceable to you, that is like on the Internet. So like if you were to Google yourself, like what would come up and just, or even on Facebook, like all of the things that you posted and so just whatever is out there for people to see, and can be traced back to you” (Participant 2AF).

“What people can see on your Facebook wall” (Participant 8AM).

Whether good or bad, most participants agreed that a digital legacy consisted of items created or manipulated by the individual. While individuals could have many digital items on their hard drive or in their webspace, only those that bore the unique “touch” of the individual could be considered part of their digital legacy:

“If I created it then you know I would consider it my digital legacy…I don’t think something can be my legacy that I’ve just bought, you know?” (Participant 2CM)

“A record of all your thoughts, stored electronically…all your documents” (Participant 5AF).

Participant 5CF described this creation and manipulation more broadly:

“It would be digital objects that had um, a person had consciously acquired either through creation or through just acquisition.”

The “consciously acquired” aspect of this definition also recalls research on collecting behavior: collectors often viewed their collections are representations of themselves, mainly through the act of bringing together items that adhered to self-defined boundaries (Belk, Wallendorf, & Holbrook, 1991).

While participants did not always agree on who would control the creation of a digital legacy or the content of the legacy, most participants agreed on a purpose: that it benefited other people, specifically one’s children. When discussing a digital legacy, several participants expressed that they had no desire to create a digital legacy, specifically because they did not have children.

“I don’t have children, I’m not that close to the other members of my family, um my husband…I wouldn’t expect him to outlive me by much, so you know I mean he could…ya know, who would want it? Who would want my digital legacy, I’m not sensing people will be um, clamoring for it” (participant 5CF).

Those that did mention having children expressed that the digital legacy, and the preservation of any digital possession that extended beyond their life, was for their children:

“things that I guess I’ve created like pictures that have signif-, important information, connect to me and are an important part of our family that I would like to keep” (Participant 6CM).

“I would have to say is what you leave behind of yourself, um, things that you keep about your family, or my son or my daughter would want to look at to see how I was like, what kind of a person I was back then, and what I was growing up, what I am now, or what I was now for whatever reason” (Participant 7BM)

Some participants mentioned that digital possessions could be of use at funerals, to create digital memorials that can be made available online or through Facebook, and that such products would be considered part of a digital legacy. Participant 2CM described this concept as “a fond farewell to family and friends.”

Overall, these five characteristics described the purpose (for other people), context (tells a story; created or manipulated by the individual), and tone (a positive light or potentially negative evidence available to the public via the Internet) of a digital legacy. However, participants were only interviewed about general descriptions of a digital legacy, not the specific content of which a digital legacy consists. Part 2 of the study explores the concept of a digital legacy by exploring participants’ descriptions of items of which a digital legacy would consist.

4.2. Part 2: Significant Characteristics of the Digital Possessions that Compose a Digital Legacy

In Part 2 of the study, 48 participants ranked 60 statements characterizing the digital possessions that they would consider maintaining for a digital legacy. The 60 statements (the Q sample) were created from common utterances reported in the interviews that explored the characteristics of digital possessions, reported in Cushing (2013). As displayed by Figure 1, the language from commonly coded areas of the interview transcripts was used to create the Q sample statements.

The 48 participant sorts were analyzed using Q factor analysis, using the computer program PQ Method.PQ Method provided factor loadings for each of the 60 statements in the Q sample. Each of the five factors represents a distinct opinion about the characteristics of the digital possessions that participants would like to maintain for a digital legacy. The participants that load onto one distinct factor shared opinions and thoughts about the characteristics of the digital possessions that they would choose to compose their digital legacy. It is important to note that the participants that loaded on a similar factor perceived common characteristics of the digital possessions they would consider maintaining for a digital legacy, not common digital possessions.

This data allowed the researcher to understand that five significant viewpoints exist that describe the characteristics of the digital possessions that individuals would like to maintain for a digital legacy. Table 3 displays the factor loadings for each participant. Forty-one of the 48 participants displayed a significant loading onto one factor, suggesting that seven of the 48 participants did not hold a strong opinion about the issue at hand. Digital photos were the most common digital possessions chosen. In addition, Facebook, digital music, and personal websites were also chosen. However, as detailed above, the most significant data was the opinions about the digital items, not the digital items themselves. Defining sorts for each Factor (cluster of individuals who similarly ranked the statement cards for each sorting task) are bolded, based on Schlinger’s (1969) formula to determine significant Factor loading: 3*1/ √n.

Table 3 displays the significant factor loadings (in bold) for each participant, organized by age. For example, the first row lists the factor loadings for Participant 5: the figure in the column for factor one is bolded, so Participant 5 loaded onto Factor 1.

As is standard in Q method, each factor will be explored in order to understand the significant characteristics each factor describes. The most and least indicative statements determine the characteristics of each factor and are described below. Q sort statements are listed as being associated with primary (P) or secondary (S) value. Digital photos and Facebook profiles were the most commonly selected digital possessions, across all factors.

Eleven participants loaded onto Factor 1. Table 4 displays the demographics of participants who loaded onto Factor 1, as well as a sample of the digital possession they had in mind when completing the sorting task. As is displayed by Table 4, common digital possessions were used for reflection across all factors. Participants were not asked to provide additional detail about their chosen digital possession, as data collection focused on gathering information about their opinions about the possessions, rather than basic detail on the possessions themselves. While all age groups were represented, the majority of participants who loaded onto Factor 1 fell into the 18-24 Age Group and werefemale. Most participants who loaded onto Factor 1 chose digital photos as the digital possession they would most like to maintain for a digital legacy.

Table 5 displays the defining statements for Factor 1, the average -5 to +5 distribution ranking for the statement, as well as the archival value category and possession value category linked with the statement, as reported in Table 2. According to Table 5, participants who loaded onto Factor 1 favored primary archival values when ranking the characteristics of the digital possession they would most want to maintain for a digital legacy. “There is no hard copy of it” and “It’s easy to use” were both ranked +5 and are associated with primary value and “description and use.” Over all, four of the eight positively ranked statements were associated with “description and use” at the possession level. From these statement rankings, it is evident that participants who loaded onto this factor were most concerned with a possession’s descriptive characteristics and the possession’s potential future use when considering which digital possession to maintain. This finding is bolstered by the negatively ranked statements of the factor, demonstrating a strong distaste for self extension characteristics. The statements that loaded onto factor 1 demonstrate that participants valued possessions for how they were intended to be used, not for the possessions’ ability to contribute to identity.

According to table 6, eight participants loaded onto Factor 2. In contrast to Factor 1, 63% of the participants loading onto Factor 2 are male and most fell into the 58-67 Age Group. While the positively ranked statements were associated with a mix of primary and secondary values, participants who loaded onto this Factor favored digital possessions for how they could be used (“It helps me function,” “It helps me forget”), such as providing evidence (“it acts as a witness to creativity”). In addition, the data suggests that the possessions would represent parts of their identity (“It represents a side of me,” “It represents quirks about me”), but not all of it. While these participants imbued their chosen possession with some characteristics of self extension, the negative statement rankings suggest that they would not go so far as to agree with statements that suggest their possession could completely represent their identity.

Seven participants loaded onto Factor 3 (Table 7). Males and females loaded equally onto this factor, and half of all participants who loaded onto this factor were member of the 38-47 Age Group. Participants who loaded onto this factor were slightly more likely to perceive secondary value in their digital possession, as demonstrated by the positively ranked statements (“It represents quirks about me,” It’s a visual representation of a memory”). According to the table, these self extension characteristics were associated with the self and one’s own memories, in contrast to one’s family and experiences, as suggested by the negatively ranked statements.

According to Table 8, nine participants loaded onto Factor 4. More females than males loaded onto this factor, and half the participants were members of the 38-47 age group. Most of the statements that positively loaded onto this factor were associated with secondary values. Participants who loaded on this factor strongly believed that their digital possession could act as a memory aid, as suggested by the positively ranked statements (“It helps me remember,” “It helps me remember my childhood,” “It’s nostalgia”). These participants’ ability to perceive their possessions as imbued with memories is clearly associated with characteristics of self extension, a secondary value.

As displayed by Table 9, six participants loaded onto Factor 5. Considering the positively ranked statements, participants loading on Factor 5 most associate their chosen digital possession with secondary values. The highest ranked statement (“It has sentimental value”) is associated with attachment, which can be perceived as a “step above” self extension, as attachment is defined by self extension characteristics, as well as an emotional connection and personal history with the possession. Findings suggest that these participants were motivated to maintain their digital possessions due to the deep connection they feel to the possessions. This is supported by the negatively ranked statements that are in stark contrast with attachment characteristics, such as “I don’t think of it as a possession.”

Collectively, Factors 1 through 5 represent participants who perceived the digital possessions that they would most like to maintain for a digital legacy as associated with increasing levels of characteristics associated with the concept of secondary value. Participants who loaded on Factor 1 perceived digital possessions to only marginally contribute to their identity and opted for statements more closely associated with primary value, while for participants loading onto Factor 5, digital possessions significantly contributed to their sense of identity, a secondary value. This finding suggests that most individuals that engage in maintaining a digital legacy would approach the task understanding that digital possessions contribute to their identity at one of five incremental levels, as delimited by the factors. The finding that participants across all factors chose similar digital possessions (digital photos and/or Facebook) suggests that this “level of self extension” in which a digital possession can be imbued varies according to individual, not type of possession. If a participant perceived that one of their digital possessions represented them, then they will perceive most of their digital possessions to represent them. In contrast, if the participant perceived one of their digital possessions to contribute little to their identity, then they will likely perceive most of their digital possessions in the same manner. A participant’s conceptual understanding of their digital possessions as a collection had the most influence on digital legacy, while type of digital possession had little effect. The digital possessions that contributed to a digital legacy did so for the personal value with which they were imbed, not because of their primary properties. A digital photo was not significant for it’s properties as an image, but rather the individual sense of meaning the photograph provided.

These findings suggest that a “one size fits all” approach to maintaining digital possessions for a digital legacy that preference specific types of digital items will be insufficient, as individuals will perceive all their digital possessions that they would consider maintaining for a digital legacy similarly. Information professionals who attempt to assist individuals with maintaining their digital legacy would be wise to learn at what level the individual perceives their digital possessions to represent their identity, before helping them select what to maintain items to maintain for a digital legacy. For some individuals, identity will be an important characteristic of their digital legacy, and for others it will not matter much at all. An individual’s stated purpose of maintaining a digital legacy will also play an important role.

5. Discussion

When combined, the results of Part1 and Part 2 of the study can provide detailed information about how individuals define a digital legacy as a general concept (Part 1), as well as a collection of possessions (Part 2). Part 1 results established that participants defined a digital legacy according to purpose, context, and tone. As a general concept, digital legacies:

∙ display a progression, tell a story (context);

∙ represent the individual (in a good light) (tone);

∙ provide evidence of the individual, usually on the internet (tone);

∙ are created or manipulated by the individual (context);

∙ and are specifically maintained/developed for people other than the individual (purpose)

These findings suggest that the act of maintaining a digital legacy is similar to an act of collecting: boundaries are created and the items that are added to the collection have a secondary value, as was discussed by Belk (1995) and Rigby & Rigby (1944) as removed from use. However, Part 2 of the study found that participants described the digital possessions that they wanted to maintain for a digital legacy according to a mix of characteristics associated with primary and secondary values. The mix of the characteristics depended on the individual, with some participants favoring more primary value classified statements and other participants favoring more secondary value classified statements. There were five distinct combinations of characteristics (factors) overall.

Previous research indicates that collecting behavior is associated with secondary value (Belk, 1995; Belk et al., 1991; McIntosh & Schmeichel, 2004; Muensterberger, 1994; Pearce, 1992; Rigby & Rigby, 1944). The question then arises: are the participants from Part 2 of the study that loaded onto factors that favored characteristics classified as primary values acting as collectors? Or, can the practice of maintaining a digital legacy only be considered an act of collecting for those individuals that perceive secondary value in their digital possessions? It is possible that the participants who preferred more primary value characteristics aligned more closely with Jones’ (2008) maintaining for later, rather than “maintaining for our lives and beyond,” of which the concept of a digital legacy more closely aligns. Future research is needed to parse this issue. The findings of this study indicate that collecting theory will be useful as researchers continue to explore the concept of a digital legacy as a sum of digital possessions.

In previous research on personal digital archiving, the act of personal archiving was often reinforced with motivations of preserving self and identity (Kaye et al., 2006; Kirk &Sellen, 2010). This is similar to how scholars of collecting theory explain the act of collecting. Several archival scholars have suggested promoting personal archiving with this connection to the concept of the self and identity (Cox, 2008; John et al., 20100). The findings from Part 2 of this study suggest that promoting personal archiving as related to identity could appeal to individuals who imbue their digital possessions with secondary value (with opinions and belief similar to those participants who loaded onto Factors 3, 4 and 5), but not all individuals (those participants loading onto Factors 1 and 2). Therefore, it is important to understand individuals’ unique personal relationships with their own digital possessions, so the marketing of personal archiving on the basis of identity could be calibrated for each individual. The hurdle then becomes how information professionals could most efficiently gather information about an individual and their opinions and beliefs about their digital possessions, in order to explain and promote maintenance of personal digital material to meet each individual’s needs.

This study was exploratory, and was a first attempt at exploring how individuals differ in their understandings of a digital legacy and the characteristics of the possessions that compose a digital legacy. More research is needed to understand the different combinations of archival values with which individuals associate their digital collections. While linking personal archiving to the concept of identity will appeal to some individuals, it will not appeal to all. Those individuals who do not prefer secondary values should not be ignored by the information literature. It will be important for research to continue to explore personal archiving behavior beyond the concept of identity in order to fully understand all motivations for preserving personal digital material for a digital legacy.

6. Conclusion

While Part 1 of the study found that participants used five specific characteristics to define the concept of a digital legacy, Part II of the study found that individuals described the digital possessions that make up a digital legacy using characteristics associated with five combinations of primary and secondary values (factors). Maintaining a digital legacy was associated with secondary values for some participants, which was similar to previous definitions of the act of collecting. In working with these “secondary valuers” or more fittingly “imbuers,” information professionals can utilize previous research on collecting theory, especially research that is associated with identity. For other participants, maintaining a digital legacy was closely associated with characteristics that represent the primary value of the digital items. This raised questions as to whether maintaining a digital legacy is analogous to the act of collecting, or if maintaining a digital legacy can only be considered an act of collecting in some cases. The study above begins to explore the issue of the digital legacy and how it has potential to be used as a resource for information professionals as they attempt to address personal digital archiving with users. Finally, while connecting the concept of identity with personal digital archiving may appeal to some individuals, it will not appeal to everyone. As archivists and librarians continue to promote personal digital archiving best practices, it will be important to explore how these may be marketed to meet the unique needs of all individuals, not just those individuals concerned with identity. Future research needs to explore how individuals may still want to maintain their digital possessions without a consideration of identity.

References

- Belk, R. W., (1988), Possessions and the extended self, Journal of Consumer Research, 15(2), p139-168.

- Belk, R. W., (1995), Collecting in a consumer society, London, UK: Routledge.

- Belk, R. W., Wallendorf, M., Sherry, J. F. Jr., & Holbrook, M. B., (1991), Collecting in a consumer culture, In Highways and buyways: Naturalistic research from the consumer behavior odyssey, p178-215, Provo, UT: Association for Consumer Research.

- Cox, R. J., (2008), Personal archives and a new archival calling : readings, reflections and ruminations, Duuth, Minn: Litwin Books.

- Cunningham, A., (1994), The archival management of personal records in electronic form: Some suggestions, Archives and Manuscripts, 22(1), p94-105.

- Cunningham, A., (1996), Beyond the pale? the ‘flinty’ relationship between archivists who collect the private records of individuals and the rest of the archival profession, Archives and Manuscripts, 24(1), p20-26.

-

Cushing, A. L., (2013), “It’s the stuff that speaks to me”: Exploring the characteristics of digital possessions, Journal of the American Society of Information Science and Technology, 64(8), p1723-1734.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.22864]

-

Furby, L., (1978), Possession in humans: an exploratory study of its meaning and motivation, Social Behavior and Personality, 6(1), p49-65.

[https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.1978.6.1.49]

- John, J. L., Rowland, I., Williams, P., & Dean, K., (2010), Digital lives: personal digital archives for the 21st century, an initial synthesis, London, UK: British Library.

- Jones, W., (2008), Keeping found things found: the study and practice of personal information management, Boston: Morgan Kaufmann Publishers.

-

Kaye, J., Vertesi, J., Avery, S., Dafoe, A., David, S., Onaga, L., … Pinch, T., (2006), To have and to hold: Exploring the personal archive, In Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems, p275-284, Presented at the Conference on human factors in computing systems, Montreal, Quebec, Canada: ACM.

[https://doi.org/10.1145/1124772.1124814]

-

Kirk, D. S., & Sellen, A., (2010), On human remains: Values and practice in the home archiving of cherished objects, ACM Transactions on Computer‐Human Interaction, 17(3).

[https://doi.org/10.1145/1806923.1806924]

-

Kleine, S. S., Kleine, R. E.,. III, Allen, C. T., (1995), How is a possession" me" or" not me"? Characterizing types and an antecedent of material possession attachment, Journal of Consumer Research, 22(3), p327-343.

[https://doi.org/10.1086/209454]

- Levinson, D. J., (1990), A theory of life structure development in adulthood, In Alexander, C. N., & Langer, E. J. (Eds.), Higher Stages of Human Development, New Yokr, NY: Oxford University Press.

-

Marshall, C.C., (2008a), Rethinking personal digital archiving part I: Four challenges from the field, D-Lib Magazine, 14(3/4).

[https://doi.org/10.1045/march2008-marshall-pt1]

-

Marshall, C.C., (2008b), Rethinking personal digital archiving part II: Implications for services, applications and institutions, D-Lib Magazine, 14(3/4).

[https://doi.org/10.1045/march2008-marshall-pt2]

- Marshall, Catherine, C., Bly, S., & Brun-Cottan, F., (2006), The long term fate of our digital belongings: Toward a service model for personal archives, In Proceedings of Archiving 2006, p25-30, Presented at the Archiving 2006, Ottawa, Canada: Society for Imaging Science and Technology.

-

McIntosh, W. D., & Schmeichel, B., (2004), Collectors and collecting: A social psychological perspective, Leisure Sciences, 26(1), p85-97.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400490272639]

- McKemmish, S., (1996), Evidence of me, Archives and Manuscripts, 24(1), p28-45.

- McKeown, B., & Thomas, D., (1988), Q Methodology, Newbury Park, NJ: Sage Publications.

- Miles, M.B., & Huberman, A.M., (1994), Qualitative data analysis, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Muensterberger, W., (1994), Collecting: An unruly passion, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

-

Odom, W., Zimmerman, J., J, Forlizzi., (2011), Teenagers and their virtual possessions: design

opportunities and issues, In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in

Computing Systems, p1491-1500, Presented at the CHI, Vancouver, BC, Canada: ACM Press.

[https://doi.org/10.1145/1978942.1979161]

-

Park, J. H., & Kim, H. M., (2012), Building up an IT service management system through the ISO 20000 certification, International Journal of Knowledge Content Development & Technology, 2(2), p31-45.

[https://doi.org/10.5865/IJKCT.2012.2.2.031]

- Paquet, L., (2000), Appraisal, acquisition and control of personal electronic records: From myth to reality, Archives and Manuscripts, 28(2), p71-91.

- Pearce, S. M., (1992), Museums, objects and collections: A cultural study, Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Pearce-Moses, R., (2005), SAA: Glossary of Archival and Records Terminology, A glossary of archival and records terminology, Retrieved from http://www.archivists.org/glossary.

-

Petrelli, D., Van den Hoven, E., & Whittaker, S., (2009), Making history: The intentional capture of future memories, In Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, p1723-1732, Presented at the CHI09, New York, NY: ACM Press.

[https://doi.org/10.1145/1518701.1518966]

- Rigby, D., & Rigby, E., (1944), Lock, stock and barrel: The story of collecting, Philadelphia, PA: J. B. Lippincott.

- Schellenberg, T. R., (1956), Modern archives, Principles and techniques.

- Schellenberg, T. R., (1956), Modern archives: Principles and techniques, Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Schlinger, M. J., (1969), Cues on Q technique, Journal of Advertising Research, 9(3), p53-60.

- Schultz, S. E., (1989), An empirical investigation of person‐material possession attachment, University of Cinncinnati, Cincinatti, OH.

- Schultz, S. E., Kleine, R., & Kernan, J., (1989), “These are a few of my favorite things” Toward an explication of attachment as a consumer behavior construct, Advances in Consumer Research, 16, p359-366.

- Tan, D., Berry, E., Czerwinski, M., Bell, G., Gemmell, J., Hodges, S., … Wood, K., (2007), Save everything: supporting human memory with a personal digital lifetime store, In Personal Information Management, p90-107, Seattle, Washington: University of Washington Press.

- Thomas, S., (2007), PARADIGM: A practical approach to the preservation of personal digital archives, Manchester, UK: Bodleian Library.

-

Whittaker, S., & Hircshberg, J., (2001), The character, value and management of personal paper archives, In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, p150-180, Presented at CHI01, Seattle, WA: ACM Press.

[https://doi.org/10.1145/376929.376932]