A Study on the Development of Curriculum Track for Civil Service Librarian

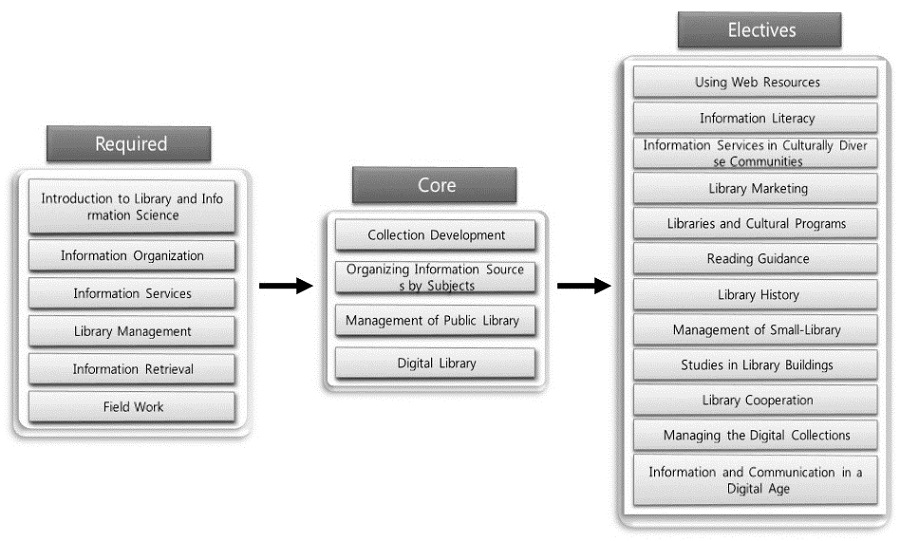

The goal of this study is to improve the competitiveness of professional librarians in society. To this end, we analyzed domestic and international LIS curriculum, determined demand from field librarians through a survey, carried out job analysis by library types, and developed an operating model for LIS curriculum by synthesizing all of these results. Finally, we suggested a course of study for civil service librarians based on this model. As a result, the six required courses for civil service librarians are: Introduction to Library and Information Science, Information Organization, Information Services (Reference and Information Services), Library Management, Information Retrieval, and Field Work. The four core courses for the civil service concentration are: Collection Development, Information Sources by Subjects, Public Library Management, and Digital Libraries. Suggested electives best suited to this career path include Using Web Resources, Information Literacy, Information Services in Culturally Diverse Communities, Library Marketing, Libraries and Cultural Programs, Reading Guidance, Library History, Small Library Management, Studies in Library Buildings, Library Cooperation, Managing Digital Collections, and Information and Communication in a Digital Age.

Keywords:

Library and Information Sciences, Core Course, Required Course, Electives, Civil Service Librarian, Operating Model for LIS Curriculum1. Introduction

With the advent of the knowledge and information society, information technology is increasingly used in every academic field, and Library and Information Science academics have labored at curriculum revision in order to best reflect the needs of this era. Therefore, research about developing courses appropriate to the digital age as well as those that enhance librarian expertise is necessary. In other words, studies have been carried out for fostering many different types of information professional, including school teacher-librarians, subject specialist librarians, technology librarians, medical librarians, law librarians, children's librarians, disability services librarians, and library marketing librarians. Furthermore, various research regarding the library system and library and information workforce as a whole have also been carried out, including studies about librarian positions and the Library Act, librarian certification system changes, subject librarian certification systems, and librarian retraining.

Also, as a diversifying society, Library and Information Science graduates' career options are very diverse, and many studies concentrate on the courses taken for each career. Many LIS departments in the United States specify the required and core courses by each career path. In recent years, South Korea LIS researchers have attempted to similarly specify required and core courses for different career paths. Past research has particularly concentrated on developing courses for students interested in becoming school librarians. Reading Instructor course research for students hoping to enter that field has also been done, at least to some extent.

However, researchers have so far ignored the task of developing career-specific courses for a variety of other career tracks. Despite the fact that many LIS students go on to be employed by agencies other than the traditional library including national information distribution agency sectors, portals, database (DB) distributors, IT companies, archives, and outsourcing companies, there are no course tracks for students to enter these fields in Korean LIS departments.

This study developed and proposed a curriculum track for students who aspire to be civil service librarians, as one of the diverse fields Library and Information Science students enter after graduation. Civil service librarians are employed by public and national libraries after passing a strenuous examination process. Their positions are supported and guaranteed by the government for life, similar to a university tenure system. The research methods used in this study and the research findings could be used as the basis for further research to develop other course tracks for students to advance in various other areas.

The purpose of this study is to suggest a method for improving the competitiveness of professional librarians by increasing their expertise. To do this, we analyzed domestic and international LIS curriculum, determined field librarians' needs through a survey, carried out job analysis by library types, and developed an operating model for LIS curriculum by synthesizing all of these results. Finally, we suggested a course of study for civil service librarians based on this model.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. The KJ Technique

This study developed the course track for civil service librarians by using job analysis as well as analysis of domestic and international LIS courses. The KJ technique is often used for curriculum development in the field of Education, but is relatively unfamiliar to the LIS field. Therefore, a brief explanation of the KJ technique and curriculum development procedure is as follows:

The KJ technique was devised by cultural anthropologist Kawakita Jiro (川 喜 田 二 郞) while conducting a field survey in Nepal and the Himalayas, and is therefore named for his English initials. He began to apply these techniques to the industry, and thereafter KJ became more widely used for defining problems and then solving them, often creatively.

To determine the course track for civil service librarians, our research team was composed of one KJ technique expert with 25 years of experience, two LIS professors, and two LIS graduate students. The KJ Technique process can be classified into the following eight steps.

1) Questioning (theme settings): The subject to be treated by the KJ technique is determined and stated clearly. Each member of the research team should understand the subject and purpose of the research before proceeding. At the same time, members to participate in the curriculum development process must be decided.

2) Collection of information: After explaining the subject arrived at in Step 1 to the participating members, they collect the information related to the stated subject matter for conducting the KJ technique. It is important to collect information from various angles within the possible range, and to avoid bias.

3) Card Making: Based on the information collected, each separate and concise aspect is recorded on an index card.

4) Card collecting and classifying : The resulting cards are then classified and collected with similar content cards into categories.

5) Label Writing: Cards collected together are given labels which summarize the contents or category of all the cards in that bunch, and these are kept together by paper clips or rubber bands.

6) Group organizing: Categories of cards should be grouped together, forming a 3-stem hierarchical relationship. The KJ Technique defines these hierarchical levels with geographic terms: Mok (目), meaning "small island" is the lowest, followed by, Kang (綱) meaning "big island", and Ryu (类), meaning "continent", which is the topmost tier. In other words, a Ryu-level category is composed of many Kangs, which is composed of many Moks.

7) Creating Associate degrees and deployment tables: Group placement based on content is finalized, and given a name.

8) Cleanup and record: Results are recorded.

2.2. Related Studies

As shown when analyzing trends in LIS curriculum research, many studies have argued that the LIS curriculum should be changed according to changes in the environment with the advent of the information era. When Korean universities began to adopt the departmental system1) in the late 1990s, LIS research mainly focused on suggesting curriculum directional changes to better reflect the characteristics of the new school system. More recently, more researchers have carried out the studies regarding the optimal course curriculum for professional librarians and subject specialist librarians (Noh, 2005).

When searching through the topic of LIS curriculum research as a whole, it is clear that there has been almost no research on the development of a curriculum for the civil service librarian. However, curriculum development research for school librarians showed significant advancements, and much of this research is also relevant to the role of civil service librarian. Of 34 Korean departments of LIS at four-year universities, Kongju National University is the only College of Education which specifically focuses on educating professional school librarians. The remaining 33 universities give teacher librarian certification to 10% of their students.

Because of this lack, many studies have proposed curriculum for prospective school librarians.

Ahn (2003) argued that school librarians of ability can keep up to date with educational paradigm shifts as well as changing needs in library service. She wrote that curriculums of library and information science departments in Korean universities need new supplementary material to foster competent school librarians. As for core courses for school librarians, Ahn suggested the following: Library Management, School Library Operations, Children and Young Adult Materials, Collection Development, Organization of Information Materials, Library Automation, Reading Guidance, Curriculum Resources Management, Educational Methods, Library Cooperation, How to Use the School Library, Reference Materials, Information Retrieval, Online Resources, Bibliography, Library Media Programs, and Digital Libraries.

Kim (2004) evaluated the present status of the curriculum for school librarians within the US education system by analyzing 31 curricula of LIS departments in the US. He concluded by suggesting three principles for a relevant operation of curriculum, and went on to study the instructional contents and strategies for school library media specialist education in Korea (Kim, 2004). He insisted several aspects of instructional contents should be emphasized for relevant school library media specialist education, including instructional contents for philosophical and conceptual aspects of the school library media specialist, knowledge and experience in literature for children and young adults, and knowledge and techniques for teaching and instruction in the field. He also suggested that LIS education for media specialists should strive to foster students to embody a strong professional sprit, help adapt themselves to school practice, and make them mindful researchers.

Lee (2007) analyzed the contents of Reading Education courses in LIS in terms of objectives, teaching methods, and problems. To accomplish this, he analyzed 19 Reading Education courses provided by LIS departments in the US and 32 from Korea. Most courses provided by the US graduate schools emphasized specific teaching techniques. However, most courses provided by Korean departments stressed more general objectives and goals. The syllabus suggested by Lee for Reading Education was composed of 13 weeks and focused on 3 main subjects: reading materials, teaching methods, and bibliotherapy.

Ham (2008) presented a curriculum for a course titled "Information and the Library" as well as discussing the roles of school librarians, especially in relation to "The School Library Promotion Law". This thesis contained the role and work of three kinds of staff in the school library, implementation of primary and secondary "Information and the Library" curriculum for information literacy instruction in the school libraries, the effects by the proposed "Information and the Library" curriculum, and its. Conclusively, school librarians should accomplish their own instructional activities with "Information and the Library" curriculum in the school curricula as differentiated work from other kinds of librarians.

In this study, I reviewed and analyzed curricula for training school librarians, under the assumption that the curricula for school librarians and civil service librarians should be developed in the same vein. Based on these studies, I proposed the courses for students to best prepare to become civil service librarians.

3. Research design and methodology

This study attempted to propose a curriculum track for the civil service librarian, thereby contributing to an increase in the competitiveness of professional librarians.

To this end, I collectively analyzed LIS curricula from Korea, the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia as well as job analysis results, suggested an operating model for LIS majors, and based on this, proposed a curriculum track for civil service librarians. The specific procedures and methods for this purpose are as follows.

First, this study identified courses currently available in Library and Information Science departments nationwide and carried out homepage searches of 34 universities.

Second, this study conducted a survey of field librarians to evaluate the practicality of the specialist courses. The courses currently available were listed and designed to be evaluated using 5-point Likert scales. Based on the results, this study was able to determine the courses with the highest degree of demand.

Third, this study explored the demand for new courses. These courses consisted were collected from 28 Library and Information Science departments in f the US, the UK, Canada, and Australia, but have not yet been launched in Korean Library and Information Science departments.

Fourth, this study derived the required courses for the civil service librarian from the job analysis of field librarians who are working in public libraries.

Fifth, based on this, we developed and proposed a curriculum track for the civil service librarian.

3.1. Analysis of LIS Curriculum Models Abroad

In order to analyze the training courses and the operational model of Library & Information Science curriculum of overseas universities, we selected LIS departments from universities in the United States, Canada, Australia, and the United Kingdom, and investigated and analyzed their curriculum for 2011. In the United States, Departments of Library & Information Science ranked in the Top 20 in colleges rated by U.S. News Education Grad Schools were selected for this study. In Canada, four universities which opened doctoral degree programs were selected. Relatively large universities were selected for study in the Australia and the United Kingdom.

The 28 universities selected for this study are shown in <Table 1>.

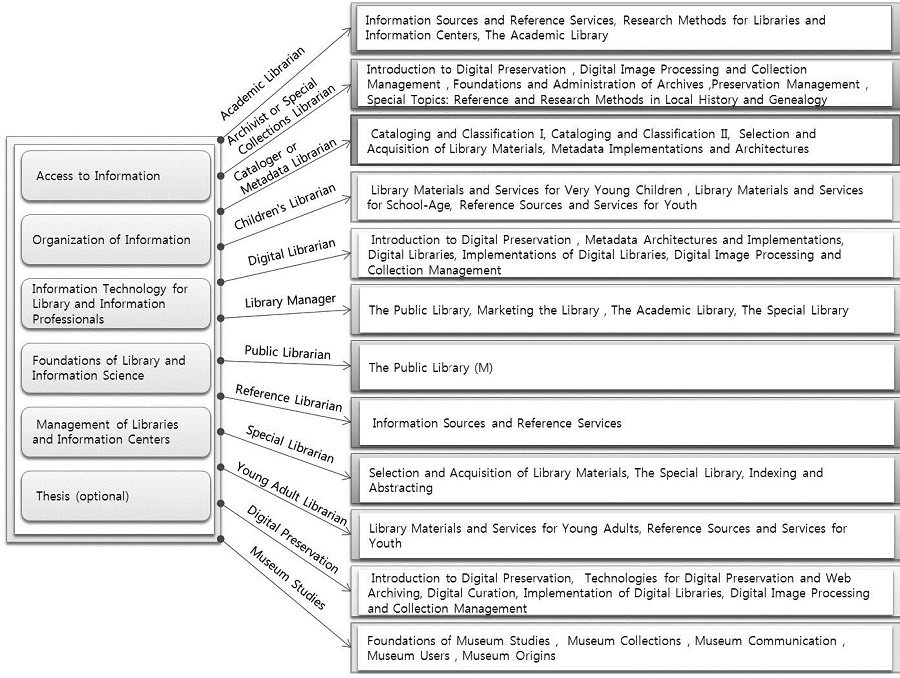

According to the analysis results of the curriculum of universities abroad, there are many cases in which different curriculum tracks are offered based on library type or librarian work area. Especially, Kent University in the US suggests courses appropriate for each career. The students in this university are recommended to take specific core and optional courses provided for each career area. The career fields suggesting model of 'LIS Career Paths and Guidesheets' presented by Kent State University will be particularly helpful to develop the Korean curriculum system. The university presents 14 different career paths, separated by library types, work fields, and the type of users.

• Academic Librarian

• Archivist or Special Collections Librarian

• Cataloger or Metadata Librarian

• Children's Librarian

• Digital Librarian

• K-12 School Librarian

• Library Manager

• Public Librarian

• Reference Librarian

• Special Librarian

• Young Adult Librarian

• Digital Preservation

• Information Technology and Information Science

• Museum Studies

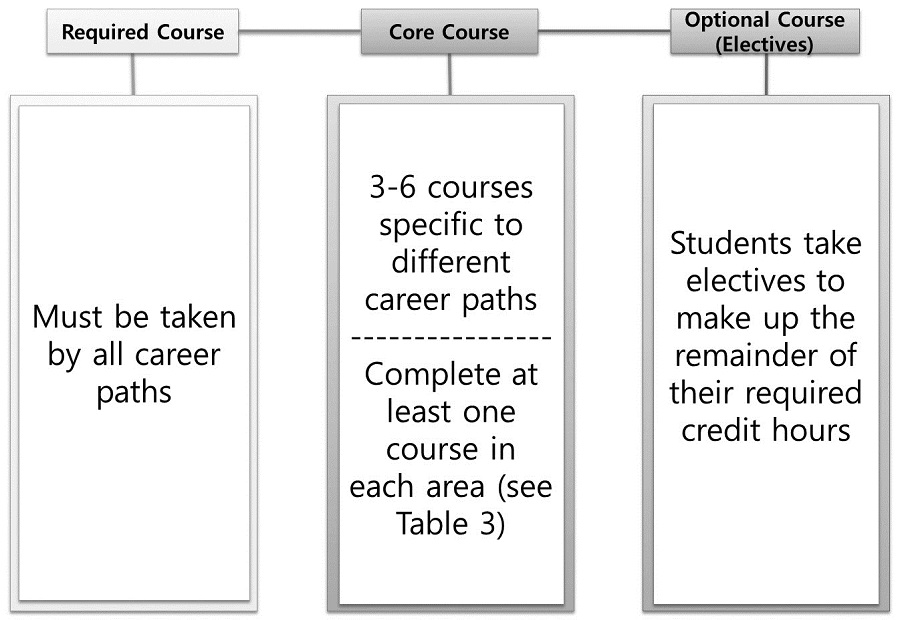

The curriculum for all career paths consists of required courses, core courses, and electives (optional courses). <Table 2> shows the six required courses, taken by all students regardless of career track.

Core courses differ based on chosen career path. As seen in <Figure 2> below, 3-6 core courses for 14 career paths are presented. Combining the required, core, and elective courses, students must take at least 18 credit hours to graduate.

Electives are categorized into three areas (A, O/R, and M), and at least one course from each must be completed regardless of career path. The elective areas are grouped as follows:

• Access to Information (A)

• Organization and Representation of Knowledge (O/R)

• Administration and Management (M)

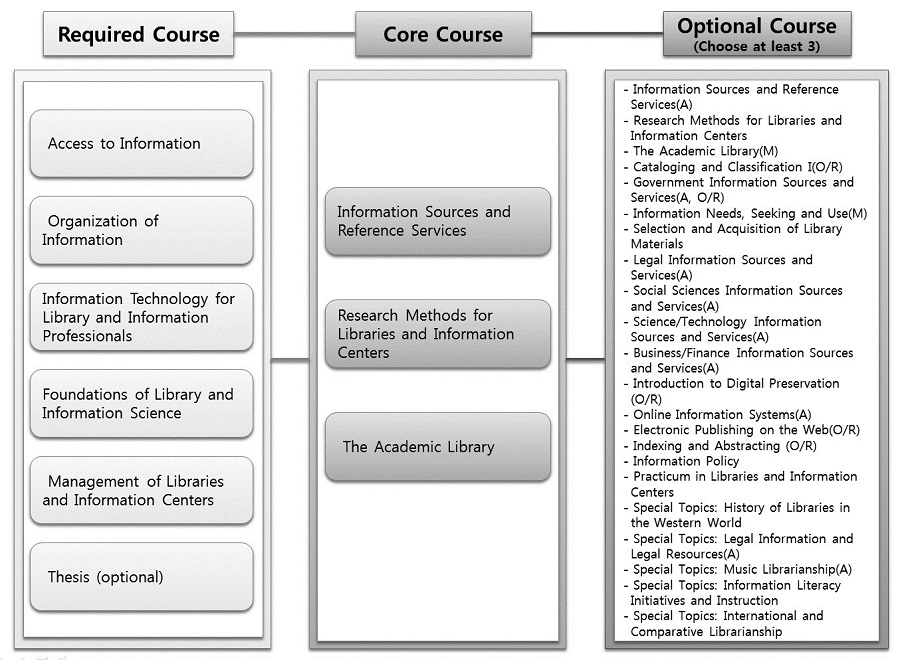

For example, students who want to become academic librarians, must complete all 6 courses presented in <Table 2>, 3 core courses (Information Sources and Reference Services, Research Methods for Libraries and Information Centers, The Academic Library) presented as the academic librarian track in <Figure 2>, and must select and take at least 3 elective courses (9 credits) in each 'A', 'O/R', 'M' areas.

Based on the above contents, the curriculum model to complete a course of training for academic librarians at Kent State University is shown in <Figure 3>. This model applies equally to other areas.

Overall, it seems that most of the surveyed US universities divided LIS courses into three areas of required, core, and electives to make up the curriculum system.

3.2. Analysis of Korean LIS Curriculum Model

In order to propose a Korean LIS curriculum model, we investigated the current curriculum models in Korea. The investigating results showed that there was no great difference between the Korean curriculum model and those found abroad. According to the results of the analysis of curriculum models from 34 LIS departments of Korean four-year colleges, we can see that most of universities also separate curriculum into required, core, and elective courses.

In the 'A Study on the Improvement of the Librarian Certification System in Korea', Kwack, Shim, and Yoon (2009) divided LIS standard curriculum into eight areas (Introduction to Library and Information Science; Information Access and User Information Resources and Collection, the Information Structure and Organization, Knowledge Agencies and Services, Information Systems, Management and Administration, and Library Practice), and separated courses into common core, core required, required, and optional courses.

This study presented library practice as the only common core course. Five courses including Cataloging, Classification, Library System Automation, Information Service (Reference and Information Services), and Library Management, were presented as core required courses. The 11 required courses were Introduction to Library and Information Science, Library History, the Information Society, Information Seeking Behavior, Collection Development, Cataloging (Ⅱ), Information Retrieval, Databases, Library System Automation (Ⅱ), Library Cooperation, and Library and Information Policy. The remaining 16 courses were offered as electives. This study suggested that LIS departments could open courses as single-subject or multiple subjects because many courses could cover more than one aspect of the eight areas in standard curriculum. In other words, five courses, including Introduction to Library and Information Science, Professional Ethics, Library Culture and History, Information and Society, and Research Methodology, must be taught in the Introduction to Library and Information Science area, but Introduction to Library and Information Science and Professional Ethics could be taught as one course called 'Introduction to Library and Information Science' (Kwack, Shim, and Yoon, 2009).

Noh performed research on developing standard curriculum for Korean LIS education in 2009. He reviewed the eligibility criteria for librarians and school librarians, the National exam and Enforcement Decree and the Enforcement Rule associated with Certification examination, and analyzed the related research. As a result, he suggested 24 courses including 2 basic, 12 required, and 10 electives as a standard curriculum for library and information science through a focus group discussion among practicing librarians.

On the other hand, in this study, the number of courses required to complete single majors and double majors and the number of courses taken in each case depended upon whether teaching or education courses were also examined.

• Single major + No Teaching courses

• Single major + Completion of Teaching courses

• Multiple majors + No Teaching courses

• Multiple majors + Completion of Teaching courses

As a result, we found that students must take approximately 70 hours of major credits (required courses, core courses, and electives) in the case of a single major and no teaching course. But students at schools where additional courses from the Education Department are required must complete these as well as the usual load (required courses, core courses, electives).

On the other hand, the Ministry of Culture, Sports, and Tourism put out a notice titled 'Librarian qualification training courses and number of courses required to complete in the educational institution' in September 2009 (Ministry of Culture, Sports, and Tourism Notice No. 2009-49). In accordance with the Library Law Article 6, Paragraph 2, and the Enforcement Ordinance of the Act Article 4, Paragraph 2 [Annex 3], they decreed librarian qualification training courses and the number of courses required for its completion at an educational institution designated by the Minister of Culture, Sports, and Tourism as shown in <Table 4>. In addition, according to regulations on issuing and managing instruction and established rule (Presidential Instruction No. 248), this notice will be reviewed and examined based on any relevant change in law or societal conditions, and will be subjected to reconsideration measures such as revision or abolition after a certain period of time, in this case.

Required Courses for librarian certification (according to Enforcement Ordinance Article 4, paragraph 2)

The above regulation for curriculum was based on the provisions of the Enforcement Decree of the Library Law. Enforcement Rules of Library Law (Article No. 172, Ordinance of the Ministry of Education) established in March 23, 1966, 'Specification of the Education Institute' of the Article 5 and 'Curriculum' of Article 6 regulated LIS education agencies and educational process for the librarians and library staff qualifications. In other words, universities with established library science departments, the Korean National Library, library organizations which were expressly authorized by the Minister of Culture, Sports, and Tourism can be designated as Schools of Librarianship. The details of curriculum for these librarianship education agencies were presented with an asterisk (Course table) within Article 6 (curriculum).

Enforcement Rules of Library Law (Article No. 570, Ordinance of the Ministry of Education) established on March 25, 1989, 'Specification of the Education Institute' of the Article 7 and 'Curriculum' of Article 8 regulated LIS education agencies to universities with library science departments established and authorized by the Minister of Culture, Sports, and Tourism. The details of curriculum for these librarianship certification programs were presented and separated into First-class Librarian, Second-class Librarian, and Associate Librarian as shown in <Table 6>.

In the 1991 amendment to this article, in addition to the existing curriculum for qualified librarians, copyright-related courses (Copyright (Ⅰ), Copyright (Ⅱ), Comparative Copyright) were added as required courses. In the 1998 amendment, reading instruction-related courses (Reading Instruction (Ⅰ), (Ⅱ)) were added as required courses for Associate Librarian and Second-class Librarian qualifications.

However, even though the curriculum proscribed by the Library Law Enforcement Decree is for all 'Schools of Library & Information Services' there are many problems with the regulation of this system, particularly as it relates to the awarding of certification at the Associate, Second-class, and First-class librarian levels.

First, we cannot find any explanation or rationale for how these specific courses were chosen and put into law.

Second, any Department of Library and Information Science in Korea may ignore the principle that students must complete the above required curriculum without repercussion.

Third, when the Korean Library Association issues the license for Librarian certification, they have no verification process for confirming whether or not the student has completed all of the required courses. Therefore, LIS graduates can receive Librarian certification without completing the above courses.

Fourth, no Department of Library and Information Science has received a notice or memorandum about these curriculum requirements.

Fifth, when we reviewed and analyzed the curriculum of Korean LIS as a whole, the above required curriculum was not reflected in the observed Korean LIS curriculum. We also noted that the course names do not match between the two systems. For example, a copyright law course is specified as a required course for 2 year colleges, but this course was not found at those colleges.

In order to solve these problems, it seems that the Korean Library Association and the Ministry of Culture, Sports, and Tourism must take on a greater role in the process. In other words, they have to give notice to all LIS Departments about on what grounds this curriculum has been developed and on whether it is enforceable, through the Mandates.

In this regard, the results of this study seem to be the basis for developing and presenting the curriculum and credit completion of LIS departments and other irregular LIS education institutes. This study derived the new demand for new courses by reviewing curriculum from other countries as well as intensively analyzing the domestic curriculum for the past twenty years. In addition, we derived courses which librarians in the field need to do their work well through job analysis. The results of this study are presented after a holistic analysis of these factors, and will have to be reflected upon to revise the content of 2009 Notice Curriculum.

3.3. Deriving the basic model for LIS major curriculum

As shown in results of the analysis of the curricula of foreign universities, there are a number of cases where the major curriculum tracks are organized by library type and work area, and a large number of foreign universities separated the courses into three areas of required, core, and optional courses. In particular, the University of Kent in the United States has separated curriculum into essential, core, and selected courses by different career paths very clearly.

In the case of Korea, many scholars (Kwack, Shim, and Yoon, 2008; Noh, 2009; Um, 2003) insist that curriculum must be divided into essential, core, and select courses, with the Ministry of Culture, Sports, and Tourism Notice presented as such. Analysis results of the domestic curriculum showed that curriculum was already mostly separated into the essential, core, and select areas.

Accordingly, this study purposed to present the basic model for training and educating prospective civil service librarians, and to a present basic domestic Library and Information Science Curriculum model as seen in <Figure 4>. This model presents curriculum as required, core, and optional courses.

As seen elsewhere, the required courses must be completed in order to graduate from a Department of Library and Information Science, and students cannot graduate if they do not complete all of them. In addition, no matter which field students plan to enter after graduation, Library and Information Science students must complete these courses.

The core courses are specified differently based on career paths, and students must complete this group of courses in order to succeed in their career field. For example, if a student wants to become a school librarian, he or she must complete the Reading Guidance course, but students who wish to enter civil service librarianship do not.

The electives are the group of courses that offer a variety of other skills and subjects to students, who take additional courses appropriate to their aptitudes after completing the required and core courses.

4. Developing Curriculum for Educating civil service librarians

In this section, we develop and propose a detailed curriculum for the civil service librarian based on the proposed operating model in Section 4.3. In other words, we will analyze comprehensively the analysis results of foreign and domestic LIS curricula, the field librarian survey analysis results, and the results of job analysis done by the field librarians by library type. We will ultimately propose the LIS curriculum for the civil service librarians, divided into required courses, core courses, and an optional course.

In Korea, most LIS departments offered 30 to 60 courses, designated as either required, core, or optional. Taking this situation into account, this study will propose at least 30 courses: 5 required, 3-6 core, and the rest optional.

4.1. Analysis of courses tested in the civil service examination

The hiring of civil servants is based on the Civil Service Exam Command Article 37 (former test method).

A civil service librarian is a librarian who works in the library of one of the country's major institutions, the public libraries belonging to Metropolitan and Provincial Offices of Education and a local autonomous entity, and national university libraries. The form of the work is the same as the general librarians' work such as transferring knowledge and information by collecting, organizing, and providing materials. The hiring of civil service librarians is done from National Libraries, including the Korean National Library, the Library of Congress, and the Supreme Court Library, and from public libraries in the cities and provinces and national university libraries. Unlike the ordinary civil servants exam, only someone who has trained in the LIS department and holds at least an Associate Librarian Certification can take the exam for civil service librarian.

In the Appendix 1 Course Table of Various Employment Examinations of Civil Service Exam Command, the section relating to civil service librarians are shown in <Table 7>. Test subjects for open recruitment of Professional Librarian Grade 8 and 9 are the five courses such as Korean, English, Korean History, Introduction to Materials Organization, and Introduction to Information Services. Two courses such as Social Science and Introduction to Materials Organization are for special employment. In addition, test subjects for level 5 or more of Professional Librarians are presented in detail. However, when the announcement for special employment actually was analyzed, three subjects such as Social Science, Materials Organization, and Information Science are presented to the test subjects.

Additional certifications and bonus points can be given to the civil service exam appointments as follows. These additional points are very different depending on the Metropolitan and Provincial Offices of Education.

We have isolated the civil service test courses related to LIS, and they can be found in the table below.

4.2. Courses required of civil service librarians

Librarians from every kind of Korean library were surveyed to gauge the LIS curriculum demands from the field. These libraries were chosen from the registered libraries in the 2010 Library Yearbook, by library type. The yearbook includes 703 public libraries and their 3,502 librarians. The sample size was approximately 20%. 500 questionnaires were distributed; 24.20% of them (121 questionnaire) were returned.

The questionnaire used was specifically designed to meet the needs of the research being conducted, although survey questions were formulated by referring to similar studies in the past.

The survey's first aim was to discover which courses were appropriate and necessary in the field. The courses listed in the survey were selected from the curriculum survey of Korean Library and Information Science departments (Noh et al., 2009). They were chosen from each area by analyzing the courses in nationwide Library and Information Science departments on the whole, and the survey was designed so that the degree of necessity for each course would be marked on a 5-point Likert Scale. The course areas surveyed included: General Library and Information Science, Information Organization, Library and Information Center Management, Information Services, Information Science, Bibliography, and Archival Science.

Secondly, the survey attempted to investigate the opinions of librarians on core courses by asking them to mark courses which they consider core (primary) courses in the list.

Finally, to gauge demand for new courses required in the digital age, this research team discussed and selected courses, which have not been offered before in Korean Library and Information Science departments but are thought to be required today or for the future, from 28 courses in Library and Information Science departments in the US, the UK, Canada, and Australia. These courses were categorized and grouped by area, and respondents were asked to mark the necessity degree of each course on a Likert scale as well as the courses they think to be core (primary) ones.

The survey results for the public librarian are as follows in <Table 10>. Taking into account the policy that 40 to 60 graduate credits are required in the current major curriculum and most of the departments of the school can open 90 credits, the top 30 of the 93 courses presented by the survey were selected for public librarians.

We can see that the public librarians surveyed viewed Field Work, Information Materials Classification, Information Materials Classification Practice, Information Materials Organization (Cataloging), Information Materials Organization Practice (Cataloging Practice), and Collection Development as the course of utmost practicality in the field.

In the survey for demand for new courses, the public librarians evaluated that the course Library Planning, Marketing, and Assessment is most necessary, and Resources and Services for People with Disabilities and Information Minority Groups, and Information Services in Culturally Diverse Communities are required in that order. This means that the public libraries are making efforts to reach the underprivileged and underserved, including multicultural families and the disabled. This focus is closely related to the governmental policy to strengthen support for vulnerable populations.

4.3. Courses derived based on job analysis

This study attempted to determine the optimal LIS courses through the results of a public library job analysis in 2008, to be reflected in the development of a course track for public librarians. The role of the public librarian, according to job analysis, consisted of 9 responsibilities and 105 tasks. The 9 responsibilities for public librarians are as follows: 1: Information Resources Organization, 2: Information Systems Management, 3: Information Resources Management, 4: Information Service, 5: Reading Activities, 6: Culture and Lifelong Learning Service, 7: Operating and Managing a Public Library, 8: External Cooperation, and 9: Self-Development. Seven courses were developed by grouping the contents of the subject by analyzing the obligations of these nine responsibilities and the 105 tasks, separated by level of core tasks and grouped by education sector to develop specific curriculum for each course.

4.4. Developing a curriculum track for civil service librarians

This study comprehensively analyzed the courses required by civil service librarian examinations, the practical evaluation and new demand survey of the LIS courses, and job analysis results for public librarians, and developed and suggested the curriculum for the civil service librarian as shown in <Table 13>.

Even though there is a difference in the courses for an examination for Civil service librarian by the class, the top 30 of the 90 courses in the practical assessment of the Korean curriculum, the top 10 of the 30 "new demand" courses, and 16 courses from the results of the job analysis have been presented. Based on this, a total of 20 subjects were selected.

Of the total of 20 courses derived above, the required 6 course are Introduction to Library and Information Science, Information Organization, Information Services (Reference and Information Services), Library Management, Information Retrieval, and Field Work. The required core courses for work in public libraries are suggested as Collection Development, Organizing Information Sources by Subjects, Field Work, and Management of Public Libraries, and the remaining 12 courses should be offered as Electives. <Figure 5> is a graphical representation of the information found in <Table 14>.

5. Conclusion and Future Research

5.1. Conclusion

Because we now live in a heavily information-based society, with information technology applied to all academic fields, it is essential that curriculum is updated and tailored to meet the needs of this era. To quickly respond to information demands and to enhance the adaptability of those working as information experts in the center of a growing proportion of digital information services, LIS curriculum should be reassessed and reorganized according to practicality in the field in order to produce competent, skilled librarians.

To this end, in this study, we propose a course track for nurturing civil service librarians, as a way to train a professional librarian competitively leading in the information society. Civil service librarians have the status of civil servants, and are working in more than 800 public libraries around the country providing library services to citizens. Civil service librarians are very important to the nation, because they are in a position to improve the level of knowledge of the entire community of citizens by providing high-quality knowledge services.

To achieve this goal, through a literature review, survey method, case studies, and convergence of expert opinions, this study proposes a course track for training competitive civil service librarians. The proposed track in this study includes required, core, and elective courses.

First, required courses suggested for civil service librarians are 6 courses: Introduction to Library and Information Science, Information Organization, Information Services (Reference and Information Services), Library Management, Information Retrieval, and Field Work.

Second, the 4 core courses are: Collection Development, Information Sources by Subject, Management of Public Libraries, and Digital Libraries.

Third, the 12 elective courses are Using Web Resources, Information Literacy, Information Services in Culturally Diverse Communities, Library Marketing, Libraries and Cultural Programs, Reading Guidance, Library History, Management of Small Libraries, Studies in Library Buildings, Library Cooperation, Managing Digital Collections, and Information and Communication in the Digital Age.

5.2. Future Research

We would like to offer some additional research topics and challenges for improving the professionalism of civil service librarians, from the problems found in the process of curriculum improvement and Korean LIS curriculum development.

First, the Ministry of Culture, Sports, and Tourism needs to specify the required Courses of Public Notice. The Ministry of Culture, Sports, and Tourism gave notice of the curriculum which must be completed by Associate Librarians, Second-class Librarians, and First-class Librarians (Ministry of Culture, Sports, and Tourism Public Notice No. 2009-49). However, this Notice is difficult to incorporate into the standardization of curriculum because there is nothing legally binding the universities providing the education to abide by it. The Public Notice of the government agencies that can be applied to the regular curriculum is required, because this kind of Notice could contribute to standardized curriculum for qualifications and to development of courses designated for civil service recruitment.

Second, there is a need to determine the amount of courses or number of course hours necessary for Librarian Qualification. Specifically, librarian qualification training courses and number of courses required to complete the institution designated by the Minister of Culture, Sports, and Tourism, in accordance with Annex 3 of Library Law (Article 6, paragraph 2) and Enforcement Rules of Library Law (Article 4, paragraph 2). Although this is targeted at separate Librarian Educating Institutions, they may need to be applied to Departments of Library and Information Science as well. The credibility of a profession is dependent upon the rigorous, and, most importantly, consistent requirements needed to enter it. Therefore, in order to maintain the authority and independence of the librarian profession, the completion of standardized curriculum and a verification process are required.

Third, the development of a Career Supporting System for Library and Information Science is recommended. If future librarians select a career, the system would automatically present the courses and qualifications necessary in order to enter their desired occupation. This tool would be helpful to increase the competitiveness of Library and Information Science students. The Korea Library Association could play an important role in developing career paths for LIS students, and presenting the standard course track appropriate for each career path.

Glossary

1) The departmental system required that students declare a major as part of the admissions process. The previous faculty system allowed students to be admitted without declaring a major. Students took classes during their first year from a variety of departments, and then declared a major before their second year.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Patricia Ladd for editing this paper into fluent American English.

References

- Ahn, In-Ja., (2003), Developing a Curriculum of School Librarians Using a Job Analysis, Journal of the Korean Society for Library and Information Science, 37(3), p79-95.

-

Hahm, M. S., (2008), A Study on the ‘Information and the Library’ Curriculum and the Roles of Teacher-Librarians, Journal of the Korean Society for Library and Information Science, 42(3), p169-188.

[https://doi.org/10.4275/KSLIS.2008.42.3.169]

- Kim, J. S., (2006), A Study on the Instructional Contents and Strategies for School Library Media Specialist Education, Journal of the Korean Biblia Society for Library and Information Science, 17(1), p135-159.

-

Kwack, Dong-Chul., Shim, Kyung., & Yoon, Cheong-Ok., (2009), A Study on the Improvement of the Librarian Certification System in Korea, Journal of the Korean Biblia Society for Library and Information Science, 43(2), p193-213.

[https://doi.org/10.4275/KSLIS.2009.43.2.193]

-

Lee, J. W., Lee, K. M., Kim, J. H., Youn, Y. R., & Lee, E. J., (2005), Evaluation and requirement of librarians on LIS Education, Journal of the Korean Society for Library and Information Science, 39(4), p45-69.

[https://doi.org/10.4275/KSLIS.2005.39.4.045]

- Lee, M. H., (2007), A Study on the Content Construction of “Reading Education Course” in LIS, Journal of the Korean Biblia Society for Library and Information Science, 18(1), p23-44.

-

Noh, D. J., (2009), A Study on the Development of a Standard Cuniculum for Education of Library and Information Science in Korea, Journal of the Korean Society for Library and Information Science, 43(4), p451-468.

[https://doi.org/10.4275/KSLIS.2009.43.4.451]

-

Noh, Y., (2005), A Comparative Study on the Curriculum Development of Library & Information Science in Korea in Line with the Structural Shifts of the Society, Journal of the Korean Society for Library and Information Science, 39(1), p59-80.

[https://doi.org/10.4275/KSLIS.2005.39.1.059]

- Noh, Y., Ahn, I. J., & Choi, W. T., (2009), Courses for Library & Information Science in Korea, Paju: Korean Studies Information.

- Noh, Y., Ahn, I. J., & Park, M., (2011), A study on librarian service providers’ awareness and perceptions of library services for the disabled, International Journal of Knowledge Content Development & Technology, 1(2), p29-42.

- Um, Y. A., (2003), A Study on the Core Courses of the Departments of Library and Information Science, Journal of the Korean Society for Library and Information Science, 34(3), p33-49.

- US News Education Grad Schools, (2011, May, 28), Retrived from http://grad‐schools.usnews.rankingsandreviews.com/best‐graduate‐schools/top‐library‐information‐science‐programs/library‐information‐science‐rankings/page+2.