Cultural Archetype Contents for the Traditional Wedding

This research aims to perform a contextual study of the wedding customs, wedding procedures, and wedding costumes included in Korean traditional wedding culture, making use of cultural contents which form cultural archetypes. The range of wedding customs studied are set limits from the Joseon dynasty to ancient times, and, for wedding procedures and costumes, to the Chosun dynasty, when a wedding ceremony became the norm. Only wedding ceremonies performed among ordinary classes are included as subjects for this research; wedding ceremonies and costumes for court are excluded. The cultural archetypes developed within these boundaries suggest prior cultural content, developed beforehand. The research methods are focused on document records inquiry and genre paintings during the Joseon era, using museum resources as visual materials.

The following is the outcome of this research: Firstly, wedding customs and procedures observed among folk materials are presented in chronological order. Secondly, the brides' and grooms' wedding costumes are also presented chronologically, differentiated by class-characteristics.

Keywords:

culture archetype contends, Traditional Korean Wedding, Traditional Korean Wedding Costume, Korean Wedding Custom, Korean Wedding Procedures1. Introduction

1.1. Necessity and Purpose of Research

Cultural archetypes are original cultural phenomena, usually presenting as general ideas or outcomes, the contents of the collective unconscious which make up national identity. Archetypal cultural contents include many different kinds of themes, accumulating from history, oral literature, folk custom, art, architecture, music, costume etc.

Cultural archetypes are very important in the 21st century when cultural industries are a pivotal axis of businesses and the economy of the nation. The commercial value in cultural contents is also very important; cultural contents should have both universalities, which give users a sense of stability, and also particularities which allow for individual expression in ways acceptable to the general public. Universality and particularity, important factors as culture contents, are both contained in cultural archetype. Cultural archetypes are outcomes which have been passed from particular areas or ethnicities by mutual agreement over a long period of time. The regional characteristics of cultural archetypes are shared within at least a village and potentially up to the level of an ethnicity, a nation, or the world. Therefore, a national cultural archetype shared within particular areas and a global cultural archetype shared all over the world are both included within cultural archetypal contents.

Research for investigating cultural archetypes has been accomplished by studying both physical and digital content, led by the Ministry of Culture and Tourism and Korea Creative Contents Agency. 'The Korean Cultural Archetypes Digital Contents Project' has been consistently researched and developed for the past 10 years. This project has played a pivotal role in increasing interest in Korean traditions and Cultural Archetypes. Research on Cultural Archetypes has taken place, not only in the academic world, but also in various fields such as myth and folklore, ornaments, and folk culture for industrial and educational use. Because such research is often separated by field and theme, there have been difficulties with research accessibility for industrial and popular applications.

Each cultural archetype content theme has connections to one another as well as a large number of contextual characteristics. Wedding culture is included within folk contents, and has some relevant legends such as Seodongyo, Princess Nakrang & Prince Hodong, all literary works which reference the marriage theme, featuring different wedding customs and ceremonies. Additionally, because the ceremony is focused on costumes, the wedding costume exists and changes according to the time and class of the participants.

The purpose of this research is to analyze contextual studies about wedding customs, wedding procedures, and wedding costume, which are all ways of expressing a convention.

The purpose of this study is to present:

firstly, the wedding customs and procedures which belong to folk traditions in Korean wedding culture.

Secondly, the different wedding costumes for brides and grooms organized chronologically and by different class characteristics.

1.2. The range and plan of this research

For wedding customs, the range of research extends from ancient times to the Joseon dynasty, and, for wedding procedures and costumes, the range is limited to the Joseon dynasty, which is when the wedding ceremony was standardized. Only wedding ceremonies for the ordinary classes are included as subjects for this research; wedding ceremonies and costumes for royal families are excluded.

There are various definitions and understandings of cultural archetype contents. However, the boundary for discovering a new cultural archetype is defined by analyzing and showing its divergence from prior cultural contents.

This research makes use of document records inquiry and genre paintings during the Joseon dynasty as well as museum objects for visual materials.

2. The Concept and Range of Culture, Cultural contents, and Cultural Archetype

2.1. Culture and Cultural contents

The most general definition of culture is 'the lifestyle of a society or an ethnic group'. Approaches for studying it can be classified into two views: One is 'an ideological view' which understands that culture is just an 'abstract', and the other is 'a total view' which sees that culture is composed of concrete things and events. Culture is what cannot be recognized, an immaterial thing which cannot be measured. It is made up of the acquired behaviors, mental ideas, and logical constructions of a society. It is humans beyond statistics, and, some argue, a psychological defense (A. Louise). Like civilizations, culture is made up of whole of a society's knowledge, religions, arts, morals, and customs, which humans acquire semantically, as a member of that society (B. Tylor). The specific subjects for cultural study are comprised of 'the material object, the actions, the religious beliefs, and the attitudes' (L. White) which have been functioning in the context specified by symbolic actions (Korean National Commission for UNESCO, 1986).

After the Framework Act on the Promotion of Cultural Industries reform period, when the legislated cultural contents were examined, contents were defined as data or information of signs, characters, voices, sounds, and images, and cultural contents are all the information, digital and analog, which added artistry, creativity, entertainment, and popularity among cultural factors to information contents. After all, cultural contents are the concepts and materials, which include digital, digitized, and analog cultural works (Framework Act on the Promotion of Cultural Industries, 2002).

A cultural contents industry is any type of industry that deals in a form of cultural content. The general term of cultural content industry has 6 subcategories (Ja, 2006) regulated by the Framework Act on the Promotion of Cultural Industries. Each category is a culture-related industry: 1) recordings, films, and games-related industry, 2) publishing, printing, and a periodical-related industry, 3) broadcasting product-related industry, 4) cultural assets-related industry, 5) character, animation, design, advertisement, performance, artwork, and artifact- related industry, 6) collecting digital cultural contents. Each category includes the manufacture, development, production, preservation, search for, and distribution of those contents. Traditional costume and foods are included, by presidential order.

2.2. Cultural Archetype contents

According to psychologist C.G Jung, an archetype is defined as a part of the collective unconsciousness, which is a general characteristic of everyone regardless of regional or personal traits. The collective unconsciousness forms the mentality that shows super-personal nature and exists to all of us. Therefore, a cultural archetype is a universal symbol, or the output that specified the contents of collective unconsciousness which composes part of the national identity (Korea Creative Contents Agency, 2002).

Within the study of cultural archetypes, there are all kinds of original sources about both 'Korean cultural archetypes' that represent a characteristic of the ethnic culture and also 'Global cultural archetypes' that offer transcendental and historical universality as security in the global context. Cultural archetypes in their original form have intrinsic value as security, the potential for sharing and enjoying culture, and the possibility for interaction and use in cultural industries (Ok, 2005).

The raw materials or the raw data called 'original sources' or 'original data' to produce the contents of cultural industries. Original data refers to cultural contents in their original states, prior to their modification for use as a product. The term 'original data' is also known as an 'original cultural phenomenon', and also is defined as cultural archetype. The term cultural archetype was widely disseminated in mass society and cultural industries by the Korea Creative Contents Agency, which is based on the Korean Culture and Contents Agency, formed in February, 1999. Both original data and cultural archetypes are used interchangeably in that both are based on the Korean identity.

The subject of cultural archetype is largely divided into history, oral literature, folklore, art, architecture, music and costume. A myth, a legend, or a folktale are all included as examples of oral literature, and religious belief, food, clothing, shelter, seasonal customs, the four ceremonial occasions, traditional plays, and dance, festivals are all included as folklore. Patterns, letters, handicrafts, drawings, and dances are examples of art, and private constructions, public constructions, and religious facilities are all examples of architecture. Also, sounds, ritual music, and the music of daily life are included within the category of music, and status, period, regional, and functional costumes are some of the many different kinds of costumes studied (Korea Creative Contents Agency, 2002).

Cultural archetypes in their original form have intrinsic value as security, the potential for sharing and enjoying culture, and the possibility for interaction and use in cultural industries. Cultural archetypes are needed in the field to help form the games, animations, movies, television shows, characters, books, designs etc that are related to collecting cultural contents as well as their processing, manufacturing, and distribution. Though a cultural archetype may only have one subject, it can be extrapolated into OSMU (One Source Many Use) type products. Therefore, research on cultural archetypes is important for developing cultural industry content. The Lord of the Rings franchise, which is based on original source material from many ancient, medieval myths and legends, is an example of this kind of archetype utility and flexibility. The three original books by J.R.R. Tolkien have made more than 100 million dollars, and the movie trilogy based on them has recorded 2.9 billion dollars in sales. In Korea, The Wind's Son, which used Samguk Sagi, or History of the three Kingdoms, as its original source material has gained sensational popularity as an OSMU in many iterations and formats, which include dramas, musicals, and games, both in Korea and abroad. In this way, the value of the cultural archetype becomes the key to the power for new national growth, which creates added value because it is the most important factor for success or failure.

3. The Cultural Archetype contents for the Traditional Korean Wedding Ceremony

In Traditional Korean Wedding Culture, the literary subject matter presented in myths and folklore are displayed as wedding customs and wedding culture; the wedding costumes visually represent the wedding customs culture of every period, and have contextual relationships among them. Analysis data of folkloric cultural archetypes suggest the costume elements used in wedding culture as cultural contents.

3.1. Folkloric contents of the Wedding Ceremony

1) 'Cheesoohon(娶嫂婚)' of Pastoral Society and 'Seoyokjae(壻屋制)' of the origin of 'Namguiheogahon (男歸女家婚)'

The wedding is a social ceremony, the permanent, public joining of a particular man and woman. The regular ceremony had to be followed because the procedures ensured that their union was socially lasting and publicly recognized even though there were some ceremonial differences depending on era, region, and class. Therefore, when a man and woman not under societal control paired off, there was probably not a particular ceremony in ancient Korean society. However, the common wedding style has been similar since ancient times and the wedding styles which reflect each period coexist in those procedures that ensure the couple is authorized by their parents and society according to the period.

Cheesoohon(娶嫂婚): living with a sister-in-law after a brother's death' is a particular wedding custom in ancient pastoral societies, a type of wedding form practiced in Buyeo, Koguryeo, and Silla. 'Cheesoohon' is a wedding custom commonly performed, not only in ancient Korea, but other ancient pastoral societies. Men in 'Cheesoohon' societies had the right to approach their older brothers' wives or widows. The Tungus and the Manchu were tacitly allowed to have sexual relations with theirs even if their brothers were still alive. In 「Samgukji Dongeegeon」 「Buyeo」, 'Cheesoohon' was practiced in Buyeo society, 'take a sister-in-law as man's wife' and traces of it have also been found in Koguryeo and Paekje.

Connubiality in ancient societies formed the most important connection to ensure group solidarity, and the relationship developments, along with blood relations, played an important role in making up for the inadequacy between the social structure and the political system. 'Cheesoohon' also was an expedient to sustain the family and protect the family system by keeping the tribe from breaking up and preventing a loss of human resources. It also ensured a peaceful succession of property from the late older brother to the younger.

'Cheesoohon' used to be widely practiced but disappeared gradually with changing agrarian societies.

The representative characteristic of Korean traditional wedding custom is the tradition of 'Namguiyeogahon (男歸女家婚 : a groom goes to bride's house and has a wedding)' which appears in myth as a sign of a matrilineal society and an old convention passed from the Dangun period to the Joseon Dynasty. Thus, there is not a father figure in the pedigree of blood relationships which appears in ancient Korean recordings or myths, and there are not many cases like these where a man is only involved for reproduction and does not form a family.

'Seookjae' (son-in-law's house) is known as a particular Goguryeo wedding custom, and as the origin of 'Namguiyeogahon'. One of the procedures of Seookjae is making a small house which a son-in-law can stay in after a wedding is arranged orally. First, he visits his prospective in-laws and asked them for permission to live with their daughter. If they accept, the couple live together until the birth of a child, and then return to their separate families. In this case, the mother is the only parent shown on the birth certificate. Despite their time lodging together, the couple have not formed a lasting relationship and have not joined their two families. These relations can be solved honorably by the custom of Seookjae. A series of the procedures which are associated with Seookjae can be seen in folklore couples like the relationship between You Hwa and Haemosoo in the myth of Joo Mong, which is the birth myth of a nation, the myth of Goguryeo, and the folktale couples Hodong and Princess Nakrang in the King Daemoosin period, King Jeenji and Dowhaneo, and Kim Chunchoo and Moonhee. As shown in Table. 1, 'Seookjae' is the custom of the new husband living with his in-laws with his bride in the home of her birth for a while after their wedding, afterwhich she will go to her husband's house. In addition, in spite of lodging together, it shows that the couple are not considered a true, lasting relationship until a woman moves into her husband's home.

'Seookjae' is not only known as a marital custom in Koguryeo but also as the origin of 'Namguiyeogahon' in the Koryo dynasty or the Joseon dynasty as is the custom in Silla and other neighboring countries. The amount of time that the couple stays in the home of the wife's birth is not fixed; a couple may stay after a wedding ceremony is held there, they may move out for reasons such as the husband becoming a government officer, or he may move near the home of his wife's birth to support her parents after living in a different area. Because of this, a family structure is not uniform for reasons of family composition, a job and economic power etc.

2) 'Banchinyoung (半親迎)', the compromise of 'Namguiyeogahon(男歸女家 婚)' and 'Chinyoung(親迎)'

Reformers in the early Joseon Dynasty used ceremonies to create the traditions to differentiate themselves from Koryo and tried to apply 'Joojagarea (朱子家禮: behavioral norms of the home by Joohee in the Song dynasty) to the Joseon Dynasty. Paternal-centered tendencies began to appear in many different ways such as the chastity ceremony or changes in relations between wives and concubines, wedding ceremonies, and relative structures by accepting Neo-Confucianism ideology in the late Koryo dynasty.

The Confucian wedding style founded on 'Joojagarea' is based on the 'Chinyoung', Chinese wedding system against the established 'Namguiyeogahon (男歸女家婚: the groom goes to the bride's and gets married there)' wedding practice, though 'Namguiyeogahon' was the common wedding style thanks to long-standing custom. The wedding ceremony of 'Chinyoung' followed the wedding custom of China, and 'Banchinyoung (半親迎: the groom goes to the bride's and comes back with the bride right after the wedding ceremony)' style was accepted into the life of the Joseon dynasty. 'Banchinyoung' is an etiquette that demands the groom go to the bride's house and then come back with the bride the day after the wedding ceremony, at which time the bride first meets her parents-in-law. 'Banchinyoung' is a wedding style created from the process of 'Namguiyeogahon' while accepting Confucianism principles during the Joseon dynasty, representing the ideal of Confucian etiquette.

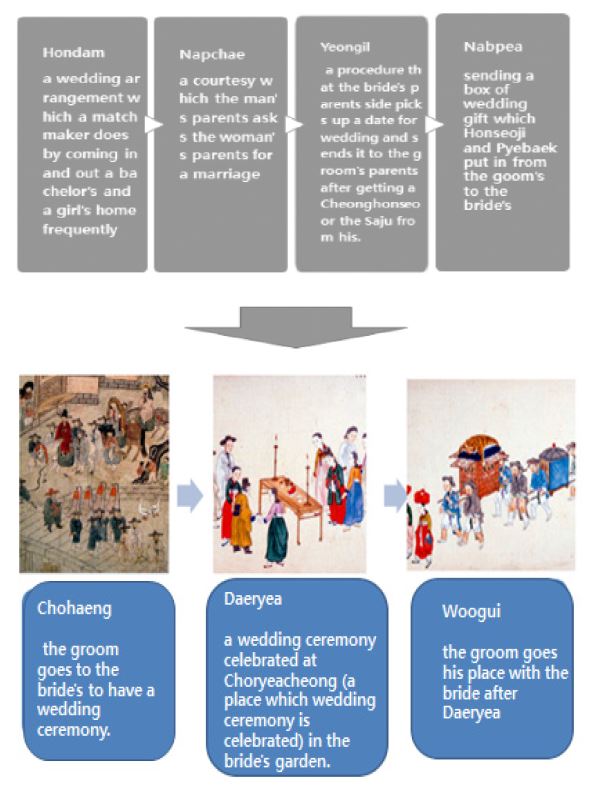

The wedding procedures can be divided into the preparation before a wedding ceremony and the process of the ceremony itself. The preparation before a wedding ceremony includes, in order: Hondam (婚談: a wedding arrangement), Napchae (納采: a proposal letter), sending a letter to the house of the fiancée (in which the Four Pillars of the bridegroom-to-be are written), Yeongil (涓吉: setting a date), and Nabpea (納幣: sending silk). As Hondam is the process of sounding out people's opinion of the proposed marriage, Maepa (媒婆: an old woman matchmaker), a woman matchmaker, or a man matchmaker arrange a marriage, going frequently between both families. Napchae is a courtesy in which the groom's family officially asks the bride's for a marriage after both families have consented to the match through a matchmaker. The groom's father sends the bride's Cheonghonseo (請婚書: a paper asking for marriage) and his Saju (四柱: one's date of birth) by official rite. Yeongil, selecting a lucky omen, is a procedure used to choose a date for the wedding and sends it to the groom's parents if the groom's then sends Saju to the bride's. Nabpea is a processes that occurs after the groom's family receives Heohonseo (許婚書: a letter allowing a marriage) and Yeongil, during which his family sends a wedding gift box containing Honseoji (婚書紙) and Pyebaek (blue silk and red silk). Nabpea is a box of wedding gifts that the groom's family sends to the bride's.

A wedding ceremony is composed of the processes of Chohaeng (初行: the beginning, when the groom goes to the bride's house), Daeryea (大禮: the most important rite in ones' life, the ceremony), and Woogui (于歸: going to the groom's house). During Chohaeng, the groom goes to the bride's house where the wedding ceremony will take place. Chohaeng begins with the groom leaving his house on a horse, accompanied by his friends and servants etc. Daeryea is the wedding ceremony during which the groom and bride, in wedding costumes, celebrate at a Choryeacheong (醮禮廳: a place where a wedding ceremony is celebrated) in the bride's garden. Afterwards, Woogui means that the groom returns to his house with his new bride. During this rite, the bride meets her parents-in-law. Woogui is usually done on the same day, but popularly can also happen three days after the ceremony.

Wedding costumes are typically the main visual method of expression for a wedding. They are regarded as being standardized in the Joseon dynasty when Confucian lifestyles became the norm and important life rites were expressed through costume. Wedding costumes for ordinary people during the Joseon dynasty are classified in grades according to status and time period.

Wedding costumes for the bride and groom were similar to clothes that only a few people were allowed to wear normally in the Joseon dynasty where the status system still existed. Grooms' wedding costumes are the uniforms of officers and brides' are the formal dress for the women in the Yangban aristocracy. Thus, no ordinary person, who was not Yangban and did not have a government post, could ever wear such clothing in daily life. Only on the occasion of a wedding ceremony were they allowed to wear official uniforms without the appropriate status level.

Samogwandae (紗帽冠帶), or the groom's wedding costume, is composed of a Samo (紗帽: a black hat government officials used to wear), Danryung (團領: a costume which has a round neckline), a Dae (帶: belt), and Heukhwa (黑靴: black leather shoes). At the beginning of the Joseon dynasty, both official uniforms and the wedding costumes for grooms were black, though Danryung in nymph pink used to be popular late in the Joseon dynasty. The groom's wedding costume represented a fantasy for the men in the Joseon dynasty, and therefore, it is thought that the color changed according to that of government officers' costumes.

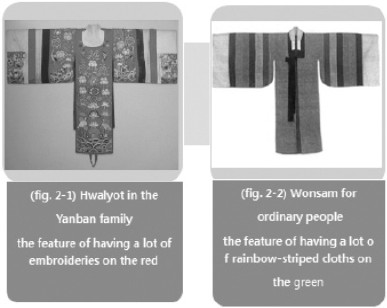

The bride's costume commonly features a Wonsam (圓衫) or Hwalyot, and Joekdoori, Hwaguan (花冠: a ceremonial coronet), binyeo (chignon hairpin), or daenggii (hair ribbons) as hair ornaments, and Yeonjeegonjee-makeup (red and black rouge spots on a bride's brow and cheek). Wonsam is the costume used as wedding costume of a court or Yanban family. Very heavily embroidered Hwalyot were worn as wedding costumes in a Yangban family (see fig.2-1). However, ordinary people mostly wore Wonsam as a wedding costume because Hwalyot represented a considerably economic burden. The Wonsam for ordinary people has been decorated with stripes of many colors (fig.2-2) instead of the flamboyance of the heavily embroidered Hwalyot. In this context, there appeared various wedding costumes in ordinary classes according to regional or economic situations.

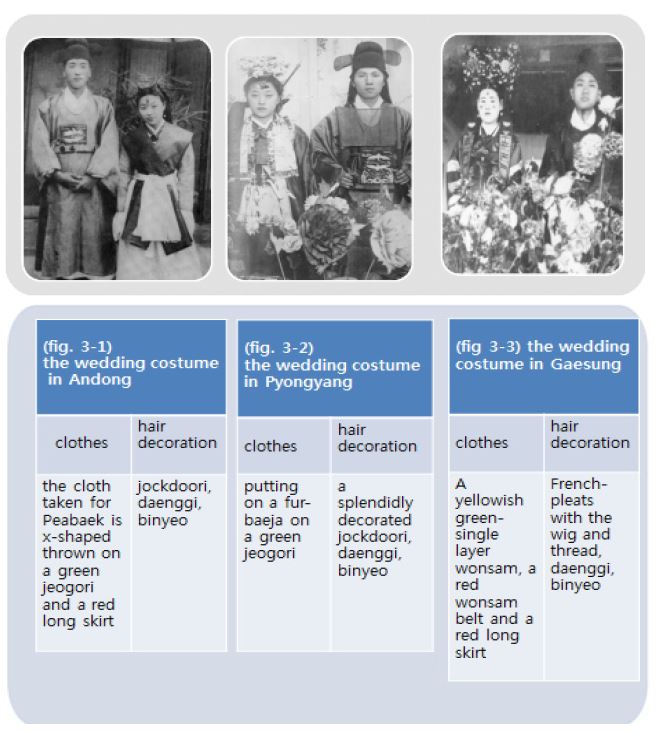

The wedding costume style used for the Peabaek ceremony is an x-shape sewn on a green Jeogori (a Korean-style short coat for women), a long red skirt, and a band encircling the waist, which was used to replace the wedding costumes in Andong (fig.3-1). In Pyongyang province, a Fur-Baeja (a vest-style costume) on a green Jeogori (see fig.3-2) was used to replace the wedding costumes. A yellowish green-single layer Wonsam, a red Wonsam belt, and a long red skirt were worn as wedding costumes in the Gaesung province (see fig.3-3).

Hwaguan and Joekdoori (coronets) are common wedding hair decorations as well as binyeo (a chignon hairpin) and different kinds of daenggis (hair ribbons). However, there are regional features among hair ornaments as well as clothes. Though Jockdoori are commonly rounded, angle-shaped ones have commonly been worn in Andong province (see fig.3-1), daenggi and binyeo were sometimes added to more splendidly decorate one like a flower (see fig.3-2), and pearl ornaments were often used on a chignon in Pyongyang province. In Gaesung province, the wig with French-pleats and hair ornaments with thread are the most specific regional features, as well as hair decorated with a binyeo and different kinds of splendid daenggis (see fig.3-3).

The hairstyles in the past were decorated with gachea (a kind of wig that looks like a bundle of hair placed on top), but a chignon has been used in its place since the Joseon dynasty. Cheunmuri and uyeomuri, which are the ornament styles of court, have been allowed as decoration for ordinary people during the wedding ceremony since the 18th century. Uyeomuri (a high placed French pleat with a bundle of several long stripes of twisted hair), the ceremonial hair style decorated with Uyum Jockdoori (made of cotton wool), Yongbongjam (龍鳳簪: a binyeo ornamented with a dragon's head shape), Tteoljam (trembling ornaments like a flower or butterfly shaped depending on motions) were used for a queen, a princess, or a daughter of a king's concubine. The chignon and ornaments known as the present traditional wedding hairstyle might have been used after the King Soonjo period, a chignon being common. Hwaguan and Jockdoori are typical ornaments used for the chignon as well as different kinds of daenggiis and binyeoes in various sizes and ornaments (see fig. 4).

Besides the costume and hair decorations, makeup is a main factor for wedding adornment. The makeup for the bride has largely been Yeonjeegonjee (a red rouge spot on the bride's cheek and a black one on the brow), made with Yeonjee. The ordinary people who weren't allowed to use Yeonjee often used red peppers cut and attached to the face or replaced the makeup with red dyed paper.

4. Conclusion

This research aimed to provide a contextual study about wedding customs, wedding procedures, and wedding costumes which is the way of expressing a courtesy and custom included in the traditional Korean wedding culture to make use of archetypal culture contents.

The subject of this study and the materials used for research purposes were the following:

Firstly, the wedding customs and procedures which derive from folk materials have been presented.

The wedding customs and procedures have been presented in chronological order. The representative wedding customs are 'Cheesoohon (娶嫂婚)' in ancient pastoral societies, 'Seookjae (壻屋制)' in the period of the Three States and 'Banchinyoung (半親迎)' in the Joseon dynasty. 'Cheesoohon' has commonly been seen not only in Korea but also other pastoral societies, and is a wedding custom to strengthen the relationship between blood relations by allowing men to sexually approach their brother's widow after a brother's death. 'Seookjae' is the origin of 'Namguiyeogahon', and is a wedding custom showing the signs of matriarchal society. The procedures of Seookjae are that the man returns to his own home following the process of visiting the woman's family, asking for lodging together, acceptance from her parents, lodging together, and childbirth. Cases where wedding procedures like 'Seookjae' are shown in the narrative structure of a myth or a folktale include the relationship between You Hwa and Haemosoo in the myth of Joo Mong in Goguryeo, and the folktale of Hodong and Princess Nakrang in King Daemoosin, King Jeenji and Dowhaneo, and Kim Chunchoo & Moonhee. 'Banchinyoung' is a wedding style created in the process of accepting and combining 'Namguiyeogahon', which is Korean native wedding culture, and the Confucianism factors of 'Chinyoung' by the Joseon dynasty. The wedding procedures by 'Banchinyoung' are divided into the preparation before a wedding ceremony and the process of the ceremony itself. The preparation processes before a wedding ceremony are 'Hondam', 'Napchae', sending the 'Saj', 'Yeongil', and 'Nabpea'. The processes of 'Chohaeng', 'Daeryea', and 'Woogui' are the wedding procedures which follow after these preparations.

Secondly, the chronological and class differences accounting for variety in bride and groom wedding costumes have been presented.

Wedding costume is an important factor of the wedding ceremony that expresses wedding ceremony roles and customs. It is regarded as having been standardized in the Joseon dynasty, when Confucian lifestyles became the norm. Wedding costumes during the Joseon dynasty varied according to status and time period. The typical style for the groom's wedding costume is considered to be 'Samogwandae (紗帽冠帶)', and its color was influenced by the changing color of government officers' costumes. The typical style for the bride's wedding costume is 'Wonsam(圓衫)' or 'Hwalyot', and 'Jockdoori' or 'Hwaguan', 'binyeo', and 'daenggii' as hair ornaments, and 'Yeonjeegonjee' for makeup. The bride's wedding costume is different according to status and time period. A formal suit for the Yangban family was 'Hwalyot', and ordinary people used to wear 'Wonsam' with a large number of rainbow- striped decorations. Ordinary people also used to wear an eclectic wedding costume falling somewhere between a formal suit and casual clothes. Hair adornment appears differently depending upon the style with gachea or a chignon. Likewise, the custom, procedures, and costume for traditional wedding ceremonies are all different according to the time period, and have contextual relationships among them.

The most important outcome of this research is for cultural archetypes in the traditional Korean wedding ceremony should be used as new cultural contents and combined with modern trends.

References

-

Ahn, I. J., (2011), Contents development of library signage manual in Korea, International Journal of Knowledge Content Development & Technology, 1(2), p15-27.

[https://doi.org/10.5865/IJKCT.2011.1.2.015]

- Hee, A. I., (2010), A case study on interpretation of costume objects of museum, Journal of the Korean Society of Design Culture, 16(2), p312-323.

- Ja, A. E., (2006), A study of a cultural classification and a culture contents industrial classification, Korean Librarian Academy, 6, p21-39.

- Korea Creative Content Agency, (2002), The Master Plan of the Digital Content of Korean Cultural Archetype.

- Ok, K. M., (2005), The study on cultural contents development methods through restoration and represent of intangible cultures, The Humane Contents Academy, 12(6), p223-248.

- Youk, S. S., (2005), The culture content and culture archetype, The Humane Contents Academy, 6(12), p75-89.

- Yoo, S. O., (1998), Korean costume, Seoul: Soohaksa.

- Yoo, H. K., (1997), The history of korean costume, Gyeonggi: Kyomunsa.

- The National Institute of Korean History, (2006), The transition of dress and decoration, Seoul: Doosandonga.

- The national institute of korean history, (2005), The custom of marriage and love, Seoul: Doosandonga.