Online publication date 31 Dec 2024

Adoption of Critical Information Literacy methods of teaching in selected University Libraries in Kenya

Abstract

This study investigated the adoption of Critical Information Literacy (CIL) methods of teaching in selected university libraries in Kenya. CIL examines effectiveness of Information Literacy (IL), disrupts inequitable systems, and creates student-driven IL instruction. This study adopted Mixed Research Methods (MRD) encompassing qualitative and quantitative approaches in form of a convergent parallel research design. The researcher used purposeful sampling by adapting an inclusion and exclusion criteria table to identify the universities, students, reference and ICT librarians that qualified for this study. The population of the study consisted of 473 respondents comprising 376 undergraduate and postgraduate students from Information Science, 14 reference/ICT librarians and 14 university librarians. The study established that the selected university libraries offered a range of CIL methods such as lecture method, virtual and orientation. The limitations of methods used in teaching CIL were that they were not interesting or motivating, did not involve critical thinking skills, lacked active learning techniques and failed to encourage the acquisition of practical skills strategies included allocation of more time for teaching CIL, sensitizing students on value of CIL, providing more ICT resources, use of interesting and clear examples.

Keywords:

Information, Information Access, Critical Information Literacy, Information Literacy, University Libraries1. Introduction

This section presents a detailed background and study objectives.

Information Literacy (IL) programs should be dynamic, created and delivered in tandem with library users, library and information resources. IL programs are mainly implemented by librarians through methods of teaching such as orientation and face- to-face training (Soltovets, Chigisheva, & Dmitrova, 2020). According to Rafiq et al. (2021) many libraries around the world have moved to electronic information resources, requiring IL programs to assist library users. The modern library users are also technology savvy. For instance, the current students are using smart phones and are mostly out of campus (Iqbal & Bhatti, 2020).

Universities are adopting online learning as an alternative to face-to-face learning (CUE, 2020). Libraries must also redesign the mode of information delivery. In Kenya, IL is mainly offered and taught by library staff through the library orientation programme (Kamau & Kanyengo, 2020). Implementation of IL in Kenya faces challenges like inadequate time and poor teaching methods. Changes such as adoption of electronic resources, embracing e-learning, pandemics such as Covid 19 and technologically savvy users, requires libraries to reflect on IL and offer effective information literacies (Rafiq et al., 2021; Head et al., 2020). Libraries need to offer effective literacies like Critical Information Literacy (CIL) to meet the needs of technologically savvy users.

CIL focuses on developing critical consciousness in student so that they learn to take control of their lives and their own learning to become active agents, asking and answering questions that matter to them and to the world around them (Akayoğlu et al., 2022). It involves creating awareness of the social and political context in which information is produced and shared, and the ability to question dominant narratives and perspectives on libraries and information provision. In summary it is student’s capacity to acquire, analyze, and comprehend information in order to make decisions about information access, production, and consumption and to take appropriate action (Didiharyono & Qur’ani, 2019).

A study by Drabinski (2019) identified several issues in CIL namely, redefining the concept of information, identifying and acting upon forms of oppression, recognizing and resisting dominant modes of information production, role of education in social change, empowering student’s learners and fighting forms of oppressions. IL should go beyond access to information and inculcate the ability to question dominant practices in the library such as inequitable access as well equipping students with ability to identify practices in the libraries. This will lead to improvement on utilization library resources. Librarians should also go beyond providing access to information and identify forms of unfairness in Libraries (Berendt et al., 2023). CIL aims at making users independent to access information resources on their own with minimal assistance from librarians. This is essential given that universities have now embraced electronic resources and online teaching (Rafiq et al., 2021). Librarians should utilize CIL approaches to maximize access to information resources.

CIL empowers the students to question dominant narratives and perspectives on library practices. CIL is important in university libraries because it helps students, faculty, and staff to become more discerning users of information. Access to information alone is inadequate to develop informed library users (Williams & Kamper, 2023). CIL is anchored on Critical Pedagogy. Critical pedagogy embraces the belief that educators should encourage learners to examine power structures and patterns of inequality through an awakening of critical consciousness in pursuit of emancipation from oppression (Darder et al., 2023).

CIL uses learner centered methods that involve the students in the learning as opposed to lecturer-based methods (Tewell, 2018). A learner-centered approach views learners as active contributors during a learning session. Learners participate in the learning by bringing their own knowledge, past experiences, education, and ideas. Learner-centered methods are practical oriented and include discussion, demonstrations and cooperative learning (Olugbenga, 2021). The study sought to establish the CIL methods used in selected university libraries in Kenya. The paper was guided by the following specific objectives.

- (1)To assess the types of methods used in teaching CIL in selected university libraries in Kenya.

- (2)Analyze the quality of methods used by librarians in implementing CIL selected university libraries in Kenya.

- (3)Determine ways of improving methods of teaching CIL in selected university libraries in Kenya.

2. Literature Review

A review on methods of teaching IL by Adzei-Stonnes (2023), Budnyk et al. (2023), and Macedo et al. (2023) established, established that libraries use several methods of teaching CIL such feminist pedagogy, problem-based learning, discussions and dialogue. However, the authors suggest that there is still room for improvement on existing methods in order to enhance methods of teaching CIL. The following subsection briefly discusses various CIL methods.

2.1 Feminist Pedagogy

Feminist pedagogy examines the use of librarian power in teaching CIL. Feminist researchers explore power relations as intersectional and based in multidimensional experiences of systemic domination (Chaulagain & Pathak, 2021). Feminist pedagogy entails mutual empathy, affection, and emotional/psychological support in the learning environment (Robinson et al., 2020). Feminist pedagogy inspires hope, as it is hopeful for personal and social transformation. The feminist pedagogues believe that CIL instructors must revive their lost personal authority and power (Robinson et al., 2020). They recognize that learners are active contributors who can make independent decisions. Librarians can use the feminist pedagogy in a variety of ways. For instance, during the literacy training sessions, librarians can use this approach to encourage students to actively participate in discussions. Several researchers such as (Roberts, 2021), Almanssori (2020) and Kier-Byfield (2021) viewed this pedagogy as movement towards effecting social change, redefining pedagogical power and authority, valuing personal experience, diversity, and subjectivity, resisting hierarchy, using experience as a resource and transformative learning.

In Africa, university libraries have adopted CIL methods in a variety of ways. In Uganda, Libraries are encouraging adoption of digital technologies to enable users to access services that were previously unavailable to them, opening new opportunities for income generation, personal development, and community engagement as well as political decision-making (Nakaziba et al., 2022). This empowerment is mainly focused towards women to empower them and help them overcome some of the inequalities and barriers to opportunity that they face (Nakaziba et al., 2022). In Kenya, Libraries have adopted the use of virtual training to deliver CIL. This approach enables libraries to reach out students off campus (Rahimi et al., 2019). Libraries in Kenya have also embraced use of remote tools such as My Library on the Finger Tips (MYLOFT) to provide information to students outside universities (Greene & Groenendyk, 2021). A study by Adomi and Oyovwe-Tinuoye (2021) established several barriers that hinder use of CIL teaching method such as lack of telecommunication network infrastructure and poor internet connectivity, inadequate resources to purchase mobile data, inefficient electric power supply. Failure to use CIL methods could leads to wastages of electronic resources. This is according to a study by Merande and Ogalo (2021) that showed that despite universities in Kenya paying substantial amounts of money on electronic resources, they remained underutilized.

Therefore, feminist pedagogy is a crucial strategy that enables library users to gain access to power structures, advancing social equity and gender equality in the information environment. Librarians should create an atmosphere where every user feels recognized and included by incorporating feminist approaches into library procedures. This will promote an equitable environment for the sharing of knowledge. Adopting feminist library practices creates places that are more inclusive, varied, and fair for learning, and intellectual development, resulting in a changing and edifying experience for all users.

2.2 Problem Based Learning

Problem-Based Learning (PBL) is a learner-centered approach in which learners learn through group work to solve a problem (Bayley et al., 2021). The problem drives the motivation and learning. PBL proponents believe that looking for answers to issues in the setting in which the knowledge will be used to helps students learn more effectively (Meng et al., 2023). PBL occurs through the process of integrating prior knowledge with information from new contexts (Wishkoski et al., 2021). In CIL, Librarians can leverage on students’ prior knowledge on Online Public Access Catalogue (OPAC) to teach new concepts such as navigating through the electronic databases to get desired information.

PBL approach has several benefits such as higher student engagement (Wagino et al., 2024) Effective use of PBL acknowledges that learning involves a problem that motivates a learner to seek out a deeper understanding of concepts. The problem will ultimately require the learner to make reasoned decisions (LaForce et al., 2017). In the PBL sessions, learners are able to develop their critical thinking skills (Suhirmani, 2022). Learners are also able to evaluate and synthesize each problem they encounter (Razak et al., 2022) so that several problem solving can be obtained rather than only one problem. PBL also enhances students’ critical thinking skills since students share their ideas with each other in looking for a solution (Razak et al., 2022). Research by Al Najjaret et al. (2021) revealed substantial enhancement of learners’ critical thinking skill when applying PBL approach. Learners can relate each concept and integrate those concepts with a real problem. This process will elicit learners’ critical thinking skills within students.

In South Africa, university libraries use PBL to teach CIL. For instance, Libraries in South Africa often design learning modules around authentic, real-world scenarios that require students to conduct research and use information resources effectively (Boss, 2022). Students are asked to solve problems related to academic projects, research papers, or case studies that simulate challenges in their academic or professional fields (Miranda et al., 2021). This shows that PBL in library instruction encourages students to work in groups, promoting teamwork and collaborative problem-solving. To achieve this, groups might be assigned a research topic and asked to collaboratively gather, assess, and organize information from various library databases, online resources, and other relevant platforms.

In Kenya, university libraries have increasingly embraced Problem-Based Learning (PBL) as a method for teaching information literacy. For instance, students are encouraged to find information using databases, academic journals, and books available in the library, critically evaluating the sources they find to make informed decisions (Chesire, 2024). In addition, students work in groups to solve problems, such as conducting a literature review on a given topic, identifying key research questions, and evaluating various resources (Uwizeye et al., 2022). Teaching CIL through PBL incorporates technological tools to help students manage information more effectively. For instance, students might use reference management tools (such as Zotero or EndNote) to organize their research, or they may use digital tools to collaborate with peers in real time, sharing notes and resources as part of their problem-solving process.

In CIL, the librarian can request students to record the information they already have about the problem and what additional information is needed to solve the problem. For instance, the students could have problems with evaluating information (Nurtanto et al., 2020). In use of PBL, the instructor guides the students to develop a strategy for resolving the problem by using various resources. The students will then assemble the information and develop a worksheet of the resources they found. Each group will present the information and review their performance. The topic should be appropriate to the discipline of the class receiving the instruction. Problem-based learning has energized how instructors and librarians share information and teach students. While changes are required, made to handle particular issues discovered during this collaboration, we have discovered that PBL provides structure and guidance to the teaching of computer literacy ideas across fields.

In order to engage users and encourage active learning, PBL should be used by librarians when teaching CIL. With this method, students can learn valuable problem-solving and critical thinking skills that will help them throughout their lifetimes in addition to absorbing information. Additionally, incorporating problem-based learning into CIL lessons can help students comprehend research ideas better and improve their capacity to implement what they have learned in practical settings, positioning them for success in their future professional and personal undertakings.

2.3 Discussions and Dialogue

Discussions is an interactive activity where learners talk with each other about a central topic, problem or concept (Khalil et al., 2020). In the CIL setting, the librarian facilitates and prompts the students to keep the discussion flowing. Discussions involve learners and therefore promote learning. The main merit of discussion is that it facilitates sharing of ideas, experiences, solving problems and promoting tolerance. Dialogue is one of the simplest ways of exploring issues such as race, gender and class (Ellinor & Girard, 2023). The merit of this method is that it allows students to participate in learning. Creating opportunities for dialogue and discussion is central to the instructional practice (Zwiers & Crawford, 2023). This method creates a good opportunity to reflect on social political issues. The facilitators of CIL can organize the class into small groups and charge each group with a task. Upon completion of the tasks, the instructor can ask each group to present their findings. The merit of this approach is that it engages the learners, and promotes peer learning.

For students to develop a thorough grasp of different viewpoints and to encourage critical thinking, discussions and dialogue should be incorporated into CIL classes. Instead of taking information at face value, this method can assist students in developing a more nuanced and knowledgeable perspective on complicated problems. Students will be better prepared to navigate the vast amount of knowledge accessible and make informed choices in their personal and career lives by participating in these thoughtful conversations.

2.4 Virtual Delivery

Virtual delivery or online teaching refers to use of information technology to deliver content (Kier & Johnson, 2022). It is one of the methods of implementing CIL. University libraries use tools such as zoom and google meet to teach CIL as opposed to face to face method (Stein and MacLeod, 2023). Virtual approaches therefore are convenient as the students do not require to attend physical classes. Users are taught using a combination of online teaching, online guides and use of audio-visual resources. This method involves use of several resources such as tutorials, games, podcasts and videos. The resources are in different formats including html, PowerPoint and pdfs (Fernández-Ramos, 2019).

Virtual delivery is hampered by several challenges including inadequate ICT facilities and staff to undertake these tasks (Jacob et al., 2021). Most institutions have been unable to fully utilize virtual learning or get full advantages of it (Okoye et al., 2023). University libraries in Kenya have attempted to offer virtual CIL efforts such as uploaded library guides and videos. According to Mohammadi, (2024) virtual delivery can make CIL creative, motivating, appealing and interesting.

2.5 Library Orientation

Library orientation is scheduled activity targeting new students aimed at familiarizing new students to the library (Abdulsalami et al., 2021). It is a method of offering CIL. Traditionally, library orientation targets new students. Library orientation aims at giving students an overview of the library. The situation is the same in Kenya, where library orientation targets new undergraduate’s students and focuses on general library services. For instance, Kenyatta University library has posted a library orientation video on its library website (Edward Safari, 2023). Librarians can use online orientation to reach out to students who are not on campus. Virtual orientation also enables the librarians to manage space issues. For instance, all the admitted first year students can be taken through orientation in one session. Virtual orientation also provides effective means of archiving the presentation.

2.6 Blended Approach

This method is also referred to as hybrid learning. Blended approach is a teaching methodology that incorporates technology and digital media with traditional teacher-led classroom activities, giving students greater flexibility to customize their learning experience (Saravanan et al., 2022). Academic libraries are using blended learning as a way to deliver CIL. This is motivated by the fact that while e-learning is taking hold, people still prefer physical people in face-to-face training environments, with theory transferred through online modules and applications done manually (Keis et al., 2017). Cay Del Junco (2024) noted that CIL is also taught through integrating contents of CIL into the curriculum. In this case, the content of CIL is included in other courses such as communication skills.

Additionally, infusion of CIL into communication skills involves giving students assignment and course activities within their subject context (Gross, Julien, & Latham, 2020). The librarian then delivers the CIL content. For instance, Communication skills units provide an ideal environment for students to integrate IL into their skills. When CIL is integrated into an academic curriculum, it becomes more meaningful to students in relation to the course activities in which they are engaged (Emisiko & Severina, 2018). In Kenya, librarians have been teaching CIL through the Communication skills which is a common unit for all first years recognizing the role of a collaborative partnership between academics and librarians will create and enhance. For example, faculty and librarians can incorporate CIL into traditional learning outcomes for assignments and research papers.

CIL skills should be taught using a blended strategy, which combines conventional instruction with cutting-edge technology to produce an effective learning environment. With this cutting-edge strategy, students are given the necessary tools for scholastic success as well as the knowledge and skills to successfully negotiate the complexities of an information-rich society, developing thoughtful and responsible digital citizens. A blended strategy allows librarians to personalize their instruction to each student’s specific requirements and tastes while also utilizing technology as a potent instrument to support and improve their learning process.

3. Methodology

This section discusses the methodology for this study. It presents the following aspects of methodology: introduction, research approach, population of the study, data collection, piloting, data analysis techniques, research reliability/ validity, limitations and Ethical consideration.

3.1 Research approach

The researcher used Mixed Method Research Design (MMRD) which integrates elements of quantitative and qualitative approaches (Creswell & Creswell, 2022). MMRD provides rigorous methods such as data collection, data analyses and data interpretation for both qualitative and quantitative data (Creswell & Creswell, 2022). This provided the researcher an opportunity to compare different perspectives drawn from quantitative and qualitative approaches (Mugenda & Mugenda, 2020). Gathering and analysing qualitative data first, then delivering the instruments to a sample, enabled the researcher to apply better contextualized research tools (Dawadi et al., 2021).

3.2 Research Design

Based on the objectives of the study, the researcher used the convergent parallel mixed methods design whereby quantitative data and qualitative data was collected concurrently in one phase (Creswell & Creswell, 2022). A convergent parallel design involves simultaneous collection of qualitative and quantitative data in the same phase of the research process, weighs the methods equally, analyses the two components independently, and interprets the results together (Mugenda & Mugenda, 2020).

3.3 Target Population

Population refers to a group of people or things under investigation and to which the study findings will be generalized (Salari et al., 2020). The target population was 473 and comprised of 431 students, 14 ICT Librarians, 14 Reference Librarians and University Librarian as shown in Table 1.

The researcher used the information on status of the universities and student’s enrolment provided by CUE publications, Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS) and inclusion and exclusion criteria to determine the number of universities and students that will be involved in this study. Inclusion Criteria is discussed in section 3.4.

CUE has grouped universities into various categories such as public chartered universities, public constituent colleges, and private chartered universities (CUE, 2022). On the other hand, KNBS provides data on the number of students enrolled in different programs per universities (KNBS, 2023). The following table show the target population.

3.4 Sampling method and sample size

The researcher used purposeful sampling by adopting inclusion and exclusion criteria and information on status of the universities and student’s enrolment provided on CUE website to sample the Universities, postgraduate’s students and reference and ICT librarians. According to Kalu (2019), purposive sampling involves selection units based on features needed in the sample. Inclusion and Exclusion criteria is used to select the respondents for research (Baltes & Ralph, 2022). According to Campbell et al. (2020), inclusion criteria entail the features that members must have to be included in a study. On the other hand, Radez et al. (2021) noted that Exclusion criteria are the characteristics that respondents must not have to be included in a study. The inclusion and exclusion criteria for universities focused on four issues namely; subscription to electronic information resources, ICT Infrastructure and engagement of ICT/Reference Librarians. The study included universities that have subscribed to Kenya Library and Information Science Consortium (KLISC) Electronic resources, paid up KENNET ICT infrastructure and engaged ICT/Reference Librarians. Universities that did meet this criterion were excluded. Regarding inclusion/exclusion of students, the study considered registration status of students, programme, level of and mode of study. The study included fourth year registered students enrolled in Library and information Science programs. Students who did not meet this criterion were not included. Regarding the library staff, the study included ICT and Reference Librarians and excluded other staff.

Questionnaires were distributed to 431 students respectively. However, data was collected from 376 respondents who returned their questionnaires hence giving a response rate of 82%. Secondly, all the twenty-eight Reference and ICT Librarians returned their questionnaires translating to a 100%. Similarly, all the fourteen university librarians honoured the interview schedules translating to a 100 % response rate. According to Creswell (2020a), a response rate of over 75 percent is satisfactory to obtain objective results in any study. The total sample size was 418 comprising of 376 students, 28 ICT/Reference Librarians and 14 University Librarians. The researcher adopted a census approach to involve all the 418 respondents in this study. This is because the target population of students and staff that met the criteria was not large.

3.5 Data Collection Procedures

The researcher used hybrid structured questionnaires, which were either in printed form or online. The questionnaires were used to collect data from students and ICT/Reference Librarians. One questionnaire was for students while the other was for the reference and ICT librarians. The reference and ICT librarians used the same questionnaire. Close-ended questions facilitated collection of quantitative data that can then be tallied into scores, percentages, or statistics that are tracked over time.

Interview schedules were used to collect data from fourteen university librarians. An interview schedule enables one to obtain data required to meet specific objectives and helps standardize the interview situation (Sekaran, 2010). It was more suitable for this study because it had open ended questions that gave room for the respondents to express their opinions. This helped in getting qualitative data. Face to face interviews were conducted and the researcher took notes. By using probing questions, interaction and genuine conversation, the researcher got deep insight into the issues concerning CIL methods of teaching.

3.6 Piloting

The pilot study was conducted at Moi University. Moi University met the inclusion criteria but was not sampled for study. Piloting the research instruments provided data that can ascertain validity and reliability of the data generated by the tool. The pilot revealed questions that are vague to create room revision. Piloting also provided feedback on effectiveness of the research questions. Feedback from the pilot study was used to improve the tools and to determine the duration of the interview sessions.

3.7 Data Analysis Techniques

This step entails data analysis, gathering data from a questionnaire, checking for data incompleteness and accuracy and removing those data that do not make any sense (Creswell & Creswell, 2022). Data was collected using questionnaires in electronic format. Data cleaning was done to identify incomplete questionnaires. Incomplete questionnaires were treated as defective. Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) was used to analyse quantitative data from the questionnaires. The researcher presented the quantitative data using descriptive statistics that uses mean, mode and standard deviations

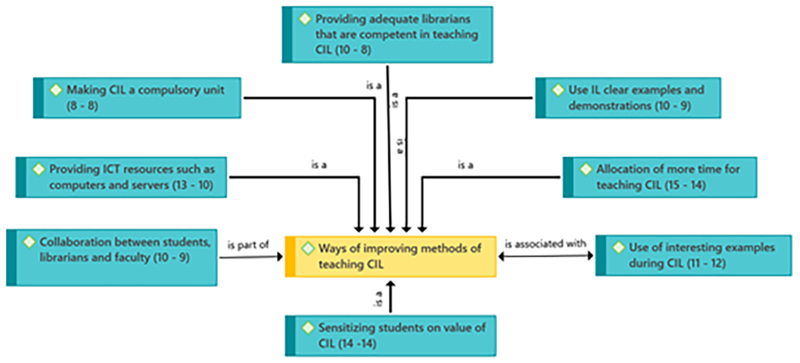

Atlas.ti was used to analyse qualitative data. The audio-recorded interviews collected for the study were thematically transcribed, analysed and classified as guided by the research objectives. The MSWord transcripts containing the qualitative data were fed into the Atlas.ti software and they provided the data presented in Figure 1.

3.8 Merging of Quantitative and Qualitative Data

The researcher used a triangulation approach to merge data. Triangulation is the process of combining qualitative and quantitative data. Specifically, the researcher used a convergent model. During the analysis phase, both data sets are compared and contrasted which forms the basis for interpretation (Mugenda & Mugenda, 2020). This method is used to compare results, confirm or corroborate quantitative results with qualitative results (Creswell, 2020).

3.9 Research Reliability and Validity

Validity is the degree to which questionnaires and interview schedules measure appropriate elements in research (Anderson et al., 2022). In this research, content validity technique was used to ensure that research instruments have content that is relevant and appropriate for the study. To achieve this, two specialists in the field were used to review independently the significance of each item in the questionnaire and interview schedule as per the purpose of the study. The researcher corrected the research instruments.

Reliability measures the degree to which the research instrument yields consistent results or data after repeated trials while validity is the degree to which results obtained from the analysis of the data actually represent phenomena under study (Rose & Johnson, 2020). The research instruments were administered at Moi University before the actual study data collection. The main objective of the pilot study was to pre-test the adequacy of the research instrument. Emphasis was put on the suitability of procedures, size of the sample, questionnaires demand and responses of each respondent, completeness and variety of information obtained.

3.10 Limitations

The researcher was restricted to limited Universities listed in Table 1. To address this, the researcher used inclusion and exclusion criteria to ensure that universities selected represent all universities in Kenya. The researcher used MMD that was rigorous and time consuming. To address this limitation, the researcher conducted a pilot study. The pilot revealed questions that were vague to create room revision. Piloting also provided feedback on effectiveness of the research questions. Feedback from the pilot study was used to improve the tools and to determine the duration of the interview sessions.

The other limitation was the tedious protocol to follow in collecting information from both the students and library staff. The researcher solved this limitation by use of consent form to assure respondents confidentiality. Informed consent allowed the respondents to volunteer their participation freely, without threat or undue coaching. In addition, the researcher faced the limitation of obtaining ethical approval from the relevant authority to conduct the research in the Universities. This limitation was addressed by initiating requests for approvals on time.

3.11 Ethical Considerations

First, the researcher submitted a written request for permission to commence a data collection process from School of Graduate and Advanced Studies (SGAS) at Technical University of Kenya (TUK). The second step involved obtaining clearance from Accredited Institutional Ethics Review Committees (IERCs) at Chuka University, thirdly, the researcher sought permission to collect data from National Commission for Science, Technology and Innovation (NACOSTI), who issued a research permit on behalf of the Government of Kenya (GoK). Last, the researcher obtained permission from the selected public universities to collect data

The researcher also ensured that the respondents were not harmed or exposed to any risk. To achieve this the researcher requested respondents to complete the consent form in appendix II to seek consent from respondents. The consent form also explained the purpose of the study and the terms of their participation such as their right to confidentiality and anonymity as well as their right to withdraw from research. The consent form also gave the researcher permission to use or share data from the respondents. The researcher also steered clear of dishonest tactics when conducting the study. The researcher also secured the data by ensuring that the computers with data are pass worded.

4. Findings

The findings of this study are presented as per objectives of this study. The following section presents the findings.

4.1 Methods used in Teaching CIL in Selected Academic Libraries in Kenya.

The first objective was to assess the types of methods used in teaching CIL in selected university libraries in Kenya. The methods used in teaching CIL in selected university libraries are in table 2.

Table 2 shows that 299 (80%), of students stated that selected university libraries offered CIL Blended integration of CIL approach, library orientation 278 (74%), virtual delivery 221 (59%) and use of multimedia 205 (55%). Data on Table 2 also shows that the selected university libraries did not offer feminist pedagogy 367 (97%), feminist pedagogy 367 (97%), problem-based learning 301 (80%), one-shot instruction 269 (72%), discussions and dialogue 221 (59%). The response from the ICT/Reference Librarians s are indicated in the Table 3.

The ICT and Reference Librarians were asked to respond to whether or not the methods of reference Table 4.17 shows that 17(61%) of ICT/Reference Librarians stated that selected university libraries offered library orientation 24 (86%), virtual delivery 18 (64%), blended integration 17 (61%) and use of multimedia 15 (53%). Results on Table 3 also revealed that selected university libraries did not offer CIL through feminist pedagogy 26 (93%), problem-based learning 25 (89%) and discussions and dialogue 18 (64%).

4.2 Quality of Methods Used in Teaching CIL Selected University Libraries in Kenya.

The study examined the quality of methods used in teaching CIL in selected university libraries in Kenya. The responses from the students on quality of methods used to teach CIL in selected university libraries are indicated in Table 4

The students were asked to respond to whether or not the methods of teaching CIL were offered by their libraries. Their responses on the quality of Interesting and motivating were as follows: The (No) responses were 206 (55%). The (Yes) responses of the same quality were 170 (45%). Their responses on quality of Involves Critical Thinking Skills were as follows; The (No) responses were 224 (60%). The (Yes) responses on the same question were (40%). Their responses on the quality of uses active learning techniques skills were as follows: The (No) responses were 212 (56%). The (Yes) responses of the same quality were 164 (44%). Their responses on the quality of encourage acquisition of practical skills were as follows: The (No) responses were 211 (56%). The (Yes) response on the same quality was 165 (44%).

The response from the ICT/Reference Librarians is indicated in Table 5.

The ICT and Reference Librarians were asked to respond to whether or not the methods of teaching CIL offered by their libraries had a quality. Their responses on the quality of Interesting and motivating were as follows: The (No) responses were 22 (79 %). The (Yes) responses of the same quality were 6 (21%). Their responses on quality of Involves Critical Thinking Skills were as follows; The (No) responses were 18 (64%). The (Yes) responses on the same statement were 10 (36%).

Their responses on the quality of active learning techniques skills were as follows: The (No) responses were 20 (72%). The (Yes) responses of the same quality were 8 (29%). Their responses on the quality of encouraging acquisition of practical skills were as follows: The (No) responses were 19 (90%). The (Yes) responses of the same quality were 9 (10%).

4.3 Suggestion on Ways of Improving Methods of Teaching CIL

University Librarians were asked to present their views on how methods of teaching CIL can be improved. The qualitative responses are shown in Figure 1.

The codes on suggestions on ways of improving methods of teaching CIL are summarized below.

- ∙ Allocation of more time for teaching CIL; 15 times

- ∙ Sensitizing students value of CIL; 14 times

- ∙ Providing more ICT resources such as computers and servers; 13 times

- ∙ Use of interesting examples during CIL; 11 times

- ∙ Use of IL clear examples and demonstrations; 10 times

- ∙ Providing adequate librarians that are competent in teaching CIL; 10 times

- ∙ Collaboration between students, librarians and faculty. 10 times

- ∙ Making CIL a compulsory Unit; 8 times

The highest response on the ways of improving methods of teaching CIL was allocation of more time for teaching CIL as revealed by the value 15. This was closely followed by Sensitizing students’ value of CIL as revealed by value 13. There were 11 responses on use of interesting examples during CIL. Use of clear examples and demonstrations; providing adequate librarians that are competent in teaching CIL and collaboration between students, librarians and faculty received 10 responses. The codes on use of IL clear examples and sensitizing students on value of CIL received 6 and 5 responses respectively. Some of the respondents verbatim are indicated below.

Allocation of more time for teaching CIL

“The library should allocate more time to learn CIL. We learnt CIL during Communication classes and the time allocated was not enough to learn all the areas. I suggest that integration of CIL in other units such as research methods.” [Librarian 1]

Providing enough resources to support CIL programme

“The University should provide more sources such as projectors and laptops to enhance teaching CIL. At the moment we are sharing the projector with many groups and at times it is not available.” [Librarian 8]

Enhancing Collaborations

“The Library Collaborates with the faculty in teaching CIL. For instance, we teach CIL during communication Skills. I would suggest that we enhance this collaboration by involving other members of the faculty.” [Librarian 12]

5. Discussion

This section discusses the findings of the study.

5.1 Methods used in offering CIL in selected University Libraries

The study findings on the methods used in delivery of CIL (see Tables 3 and 4) reveal that majority of the students (59%, 74%, 80% and 55%) and ICT/Reference librarians (64%, 86%, 61% and 53%) use blended integration, library orientation, virtual delivery and multimedia methods to teach CIL such as CIL. The findings according to majority of the students (97%, 80%, 59% and 72%) and ICT/reference librarians (93%, 89%, 64% and 86%) indicated that libraries do not use feminist pedagogy, problem-based learning discussions and dialogue and one-shot instruction respectively. These findings can be attributed to the following three reasons. One, lack of ICT resources such as internet, computers and ICT skills amongst students, libraries and librarians. In addition, students are also affected by disparities such as cultural factors and economic background. Students in well up families’ may could afford to purchase laptops and attend CIL classes as compared to students from poor family set ups. Two, librarians may need to embrace CIL methods such as feminist pedagogy, problem-based learning, discussions and dialogue and one-shot instruction. Three, librarians need to interrogate the appropriateness of teaching methods and traditional library practices such as offering CIL through communication skills. CIL empowers library users and librarians to interrogate effectiveness of the library resources and methods of teaching (Drabinski, 2019).

One way of promoting use of critical methods of teaching is through providing libraries with adequate resources such as internet and computers. Students from poor family backgrounds could assisted to purchase personal laptops through loans. In addition, librarians could organize trainings and conferences on CIL teaching CIL. Librarians could also collaborate with the faculty to improve their expertise on critical methods of teaching. Libraries can also integrate CIL approaches into other methods. For instance, feminist and PBL approaches can be incorporated in lecture and discussions methods.

Feminist and PBL will also enhance Competence Based Curriculum (CBC). Kenya recently launched the CBC which emphasizes continuous search of information through library lessons and application of knowledge in creativity, innovation and problem solving. Through feminist and PBL approaches, University Libraries can adopt the global best practices on equipping library users with critical skills necessary to make them independent lifelong learners

One of the Kenyan Government’s Bottom-up Economic Transformation Agenda (BETA) is to partner with private sector to bridge the skills gap of graduates entering the labor market. PBL and feminist approaches are core drivers of BETA given their emphasis on practical skills

Unfortunately, majority of university libraries in Kenya do not use CIL methods of teaching. According to Emisiko and Severina (2018) majority of the libraries in Kenya library use orientation to teach IL because it consolidates all the first-year students together. Research by Chaulagain and Pathak (2021) also indicated that universities in developed countries are yet to embrace feminist pedagogy which explore power relations as intersectional and based in multidimensional experiences of systemic domination. Librarians should utilize CIL approaches to maximize access to information resources

5.2 Qualities of Methods used in Teaching CIL in selected University Libraries

The findings show that majority of students (55%, 60% and 56% and 56%), ICT/Reference Librarians (79%, 64%, 72% and 68%) stated that methods used in teaching CIL resources are lacks engagement and fails to stimulate learner interest, do not involve critical thinking skills, uses active learning techniques and do not encourage acquisition of practical skills respectively. This finding highlights gaps in effectiveness of methods of teaching in delivery of CIL. This gap is attributed to the following two reasons: First, librarians may need to incorporate creativity in teaching. Secondly, the librarians may need to use learner centered methods that involve the users in the process of learners. Thirdly, librarians may need to be transformative and adopt new methods of teaching such as feminist. To achieve this, librarians should establish strong collaboration with the faculty to learn about new methods of teaching.

Building on these results Librarians could consider taking short courses on pedagogy. Secondly librarians may need to use creative strategies in teaching. A study by Trevallion and Nischang (2021) pointed out that creativity is the process of exploring possibilities, generating alternatives, keeping open mind towards change and combining ideas to create something new or to review old concepts in new ways. For instance, librarian can use active and collaborative learning strategies that involve them in the learning process. Librarians can also use inquiry-based, problem-based, or project-based learning to stimulate learners’ curiosity, creativity, and critical thinking. Similarly, inappropriate teaching methods will hinder access to information resources. A study by Nakaziba and Ngulube (2024) pointed that university libraries have not embraced modern methods of teaching CIL. The CIL approach could ensure that the methods of teaching are learner-centered, creative, and motivating.

5.3 Students preference on Methods used in Teaching CIL in Selected University Libraries

The findings on the student’s preference on methods used in Teaching CIL indicate that majority of the students (61%, 63% and 36%) agreed that they prefer virtual delivery, orientation, problem based and discussion. Majority of the students (73%) disagreed that they like one short instruction. The findings also revealed that the majority (73%) of the students disagreed that they like one short instruction. These findings indicate that the students are not conversant with CIL methods of teaching such as feminist and problem based. Students may need to be sensitized on CIL methods. Secondly, the findings reveal that students prefer methods that engage them in the learning.

Building on these results, the librarians can involve the students in evaluating effectiveness of methods of teaching CIL. Librarians can leverage on modern ICT applications such as zoom to improve on the methods of teaching. A study by Torrell (2020) pointed out that the majority of the students do not attend CIL sessions because they are mostly off campus. Another study by Omotayo and Haliru (2020) attributed student’s inability to find information resources to ineffective methods of teaching.

5.4 Suggestions on Improving Methods Used in Teaching CIL in Selected University Libraries in Kenya.

The findings from qualitative data (See figure 1) on perceptions about suggestions on improving methods used in teaching CIL show that the highest code was ‘allocation of more time for teaching CIL’ appearing 15 times. Four other significant codes were ‘sensitizing students' value of CIL’, ‘providing more ICT resources’, ‘use of interesting examples during CIL’ and ‘use of IL clear examples and demonstrations’, appearing 14, 13,11 and 10 times. This finding highlights that, most of the respondents agreed that the methods of teaching CIL can be improved through several ways. The findings show that suggestions on improving methods used in teaching should be viewed as forms of librarian empowerment. Building on these results, librarians can organize and lead workshops on information literacy and effective methods of teaching CIL.

A study by Withorn et al. (2021) pointed out that the university that librarians have not been allocated time to teach CIL and usually make local arrangements with the students. Another study by Safdar and Idrees (2021) pointed out that the majority of the students in universities are not conversant on the concept and value of CIL. The CIL approach could ensure that librarians and users are empowered to use learner centered, creative and motivating methods of teaching.

6. Conclusion

The methods used in teaching CIL were blended integration, library orientation, virtual delivery and multimedia methods. The most utilized method was communication skills. The least utilized method was feminist pedagogy. The other underutilized methods were; problem-based learning discussions and dialogue and one-shot instruction. The limitations on methods used in teaching CIL were; lack engagement and fails to stimulate learner interest, do not involve critical thinking skills, lack active learning techniques and do not encourage acquisition of practical skills respectively. The study suggested suggestions on improving methods of teaching such as allocatiom more time for teaching CIL, sensitizing students on value of CIL, providing more ICT resources, use of interesting and clear examples.

7. Recommendations

This section gives the recommendations for practice and further research based on the research objectives and the conclusion.

- a.Librarians can organize specific training programs on CIL. These trainings can be organized by Library Consortiums such as Kenya Library and Information Services Consortium (KLISC) and Kenya Library Association (KLA).

- b.Librarians in Kenya can a develop CIL policies to guide in the implementation CIL methods.

- c.Librarians can organize discussions how CIL could address broader societal issues, such as digital literacy or equity in higher education.

- d.University Librarians should develop national guidelines/Policy for Critical Information Literacy approaches

- e.University Librarians can create awareness on CIL approaches.

- f.The study recommends collaboration between the teaching staff and library on advocacy, designing, delivery and evaluation of CIL.

- g.Redesigning of IL curriculums to CIL. This should be done by librarians in consultation with the faculty.

- h.Universities Librarians should offer support to users by holding regular seminars, conferences and use of online tools.

- i.University Librarians should work closely with managements to ensure that all barriers limiting use of CIL approaches are addressed.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge with appreciation the assistance given by the journal manager, journal editors and peer reviewers.

References

-

Abdulsalalami, L. T., Ekhaguosa, V. O., & Rebecca, A. D. E. H. (2021). User’s perception about orientation program of academic library. Journal of Business Strategy Finance and Management, 1(2), 15-27.

[https://doi.org/10.12944/JBSFM.02.01-02.04]

- Adzei-Stonnes, P. (2023). Exploring academic librarians’ lack of experiential learning in teaching college freshmen information literacy skills: an interpretive phenomenological study. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=5354&context=doctoral

-

Akayoglu, S., Üzüm, B., & Yazan, B. (2022). Supporting teachers’ engagement in pedagogies of social justice (STEPS): Collaborative project between five universities in Turkey and the USA. Focus on ELT Journal, 4(1), 7-27.

[https://doi.org/10.14744/felt.2022.4.1.2]

-

Al Najjar, H., Khalil, A. I., & Bakar, S. A. A. (2021). Nursing Students’ Critical Thinking, Problem Solving and Self Directive Learning Skills: The Effect of Problem-Based Learning (PBL) Versus Lecture Based Learning (LBL). Issues and Development in Health Research, 5, 100-120.

[https://doi.org/10.9734/bpi/idhr/v5/1884C]

- Almanssori, S. (2020). Feminist pedagogy from pre-access to post-truth: A genealogical literature review. Canadian Journal for New Scholars in Education/Revue canadienne des jeunes chercheures et chercheurs en éducation, 11(1), 54-68.

-

Anderson, R., Taylor, S., Taylor, T., & Virues‐Ortega, J. (2022). Thematic and textual analysis methods for developing social validity questionnaires in applied behavior analysis. Behavioral Interventions, 37(3), 732-753.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/bin.1832]

-

Baltes, S., & Ralph, P. (2022). Sampling in software engineering research: a critical review and guidelines. Empirical Software Engineering, 27(4).

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s10664-021-10072-8]

-

Bayley, T., Wheatley, D., & Hurst, A. (2021). Assessing a novel problem‐based learning approach with game elements in a business analytics course. Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education, 19(3), 185-196.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/dsji.12246]

- Berendt, B., Karadeniz, Ö., Kıyak, S., Mertens, S., & d’Haenens, L. (2023). Bias, diversity, and challenges to fairness in classification and automated text analysis. From libraries to AI and back. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.07207, .

- Boss, S., & Krauss, J. (2022). Reinventing project-based learning: Your field guide to real-world projects in the digital age. International Society for Technology in Education.

- Boss, S., & Krauss, J. (2022). Reinventing project-based learning: Your field guide to real-world projects in the digital age. International Society for Technology in Education. ly

-

Budnyk, O., Nikolaesku, I., Solovey, Y., Grebeniuk, O., Fomin, K., & Shynkarova, V. (2023). Paulo Freire’s critical pedagogy and modern rural education. Revista Brasileira de Educaзгo do Campo, 1-20.

[https://doi.org/10.20873/uft.rbec.e16480]

-

Campbell, S., Greenwood, M., Prior, S., Shearer, T., Walkem, K., Young, S., Bywaters, D., & Walker, K. (2020). Purposive sampling: complex or simple? Research case examples. Journal of Research in Nursing, 25(8), 652-661.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/1744987120927206]

-

Chaulagain, R., & Pathak, L. (2021). Exploring intersectionality: theoretical concept and potential methodological efficacy in the context of Nepal. Molung Educational Frontier, 11, 148-168.

[https://doi.org/10.3126/mef.v11i0.37851]

- Chesire, F. (2024). Development and evaluation of the Informed Health Choices secondary school intervention for improving critical thinking about health among students in Kenya: Digital educational resources for teaching secondary school students critical thinking about health claims, evidence, and choices.

- Creswell, J. W. (2020). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research. Pearson Higher Ed.

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2022). Research design: qualitative quantitative and mixed methods approach (6th ed.). SAGE Publications. Thousand Oaks, California.

- CUE (2014). Commission for University Education - Home. www.cue.or.ke, . https://www.cue.or.ke/

-

Darder, A., Hernandez, K., Lam, K. D., & Baltodano, M. (Eds.). (2023). The critical pedagogy reader. Taylor & Francis.

[https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003286080]

-

Dawadi, S., Shrestha, S., & Giri, R. A. (2021). Mixed-methods research: A discussion on its types, challenges, and criticisms. Journal of Practical Studies in Education, 2(2), 25-36.

[https://doi.org/10.46809/jpse.v2i2.20]

-

Del Junco, C. (2024). Critical Pedagogies and Critical Information Literacy in STEM librarianship: A Literature Review. Issues in Science and Technology Librarianship, (105).

[https://doi.org/10.29173/istl2816]

-

Didiharyono, D., & Qur’ani, B. (2019). Increasing Community Knowledge Through the Literacy Movement. To Maega: Jurnal Pengabdian Masyarakat, 2(1), 17-24.

[https://doi.org/10.35914/tomaega.v2i1.235]

-

Drabinski, E. (2019). What is Critical About Critical Librarianship? How does access to this work benefit you? Let us know! Art Libraries Journal, 44(2), 49-57.

[https://doi.org/10.1017/alj.2019.3]

- Edward Safari (2023, November 24). Kenyatta University Library Orientation. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ChccgRnkmOM

- Ellinor, L., & Girard, G. (2023). Dialogue: Rediscover the transforming power of conversation. Crossroad Press.

- Emisiko, M., & Severina, N. (2018). Enhancing lifelong learning tendencies through IL practices in higher education institutions: a case of Cooperative University of Kenya. International Journal of Social Sciences and Information Technology, 4, 169-180.

-

Fernández-Ramos, A. (2019). Online IL instruction in Mexican university libraries: the librarians’ point of view. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 45(3), 242-251.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2019.03.008]

- Head, A. J., Fister, B., & MacMillan, M. (2020). Information Literacy in the Age of Algorithms: Student Experiences with News and Information, and the Need for Change. Project Information Literacy.

-

Iqbal, S., & Bhatti, Z. A. (2020). A qualitative exploration of teachers’ perspective on smartphones usage in higher education in developing countries. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 17(1).

[https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-020-00203-4]

- Jacob, O. N., Jegede, D., & Musa, A. (2021). Problems facing academic staff of Nigerian universities and the way forward. International Journal on Integrated Education, 4(I), 230-241.

-

Johnson, C. C., Walton, J. B., Strickler, L., & Elliott, J. B. (2023). Online teaching in K-12 education in the United States: A systematic review. Review of Educational Research, 93(3), 353-411.

[https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543221105550]

- Julien, H., Gross, M., & Latham, D. eds. (2020). The information literacy framework: Case studies of successful implementation. Rowman & Littlefield.

-

Kalu, M. E. (2019). Using emphasis-purposeful sampling-phenomenon of interest-context (EPPiC) framework to reflect on two qualitative research designs and questions: A reflective process. The Qualitative Report, 24(10), 2524-2535.

[https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2019.4082]

- Kanyengo, C. W., & Kamau, N. (2020). Information literacy policies and practices in health science and medical libraries in Kenya. Zambia Journal of Library & Information Science (ZAJLIS), ISSN: 2708-2695, 4(1).

-

Keis, O., Grab, C., Schneider, A., & Öchsner, W. (2017). Online or face-to-face instruction? A qualitative study on the electrocardiogram course at the University of Ulm to examine why students choose a particular format. BMC medical education, 17, 1-8

[https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-017-1053-6]

-

Khalil, R., Mansour, A. E., Fadda, W. A., Almisnid, K., Aldamegh, M., Al-Nafeesah, A., Alkhalifah, A., & Al-Wutayd, O. (2020). The sudden transition to synchronized online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic in Saudi Arabia: a qualitative study exploring medical students’ perspectives. BMC Medical Education, [online] 20(1). Available at: https://bmcmededuc.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12909-020-02208-z, .

[https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02208-z]

-

Kier, M. W., & Johnson, L. L. (2022). Exploring how secondary STEM teachers and undergraduate mentors adapt digital technologies to promote culturally relevant education during COVID-19. Education Sciences, 12(1), 48.

[https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12010048]

- Kier-Byfield, S. (2021). Reconceptualising feminist pedagogies in higher education: theoretical narratives, political frameworks and institutional dynamics (Doctoral dissertation, Loughborough University).

- Kukulska-Hulme, A., Beirne, E., Conole, G., Costello, E., Coughlan, T., Ferguson, R., FitzGerald, E., Gaved, M., Herodotou, C., Holmes, W., Mac Lochlain, C., Nic Giolla Mhichíl, M., Rienties, B., Sargent, J., Scanlon, E., Sharples, M., & Whitelock, D. (2020). Innovating Pedagogy 2020: Open University Innovation Report 8. The Open University. Retrieved August 13, 2024 from https://www.learntechlib.org/p/213818/

-

LaForce, M., Noble, E., & Blackwell, C. (2017). Problem-based learning (PBL) and student interest in STEM careers: The roles of motivation and ability beliefs. Education Sciences, 7(4), 92.

[https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci7040092]

-

Macedo, E., Teixeira, E., Carvalho, A., & Araújo, H. C. (2023). Exploring the renewal of pedagogy: problem-based learning as a space for young peoples’ educational citizenship. Educação e Pesquisa, 49, p.e269782.

[https://doi.org/10.1590/s1678-4634202349269782en]

-

Meng, N., Dong, Y., Roehrs, D., & Luan, L. (2023). Tackle implementation challenges in project-based learning: a survey study of PBL e-learning platforms. Educational technology research and development, 71(3), 1179-1207.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-023-10202-7]

- Merande, J., Mwai, N., & Ogalo, J. (2021). Use Of Electronic Resources By Postgraduate Users in Kenyan Selected Academic Libraries. Journal of Information Sciences and Computing Technologies, 10(1), 1-12. http://erepository.uonbi.ac.ke/bitstream/handle/11295/155910/Merande_Use%20Of%20Electronic%20Resources%20By%20Postgraduate%20Users%20in%20Kenyan%20Selected%20Academic%20Libraries.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

-

Miranda, J., Navarrete, C., Noguez, J., Molina-Espinosa, J. M., Ramírez-Montoya, M. S., Navarro-Tuch, S. A., ... & Molina, A. (2021). The core components of education 4.0 in higher education: Three case studies in engineering education. Computers & Electrical Engineering, 93, 107278

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compeleceng.2021.107278]

-

Mohammadi, M. (2024). Digital information literacy, self-directed learning, and personal knowledge management in critical readers: Application of IDC Theory. Research & Practice in Technology Enhanced Learning, 19.

[https://doi.org/10.58459/rptel.2024.19004]

- Mugenda, O. M., & Mugenda, A. G. (2020). Research methods: quantitative & qualitative apporaches, 2(2). Nairobi: Acts press.

-

Nakaziba, S., & Ngulube, P. (2024). Harnessing digital power for relevance: status of digital transformation in selected university libraries in Uganda. Collection and Curation, 43(2), 33-44.

[https://doi.org/10.1108/CC-11-2023-0034]

-

Nakaziba, S., Kaddu, S., Namuguzi, M., & Mwanzu, A. (2022). Exploring experiences regarding IL competencies among nursing students at Aga Khan University, Uganda. Library Management.

[https://doi.org/10.1108/LM-08-2022-0071]

-

Nurtanto, M., Fawaid, M., & Sofyan, H. (2020). Problem based learning (PBL) in Industry 4.0: Improving learning quality through character-based literacy learning and life career skill (LL-LCS). In Journal of Physics: Conference Series (Vol. 1573, No. 1, p. 012006). IOP Publishing.

[https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1573/1/012006]

-

Okoye, K., Hussein, H., Arrona-Palacios, A., Quintero, H. N., Ortega, L. O. P., Sanchez, A. L., Ortiz, E. A., Escamilla, J., & Hosseini, S. (2023). Impact of digital technologies upon teaching and learning in higher education in Latin America: an outlook on the reach, barriers, and bottlenecks. Education and Information Technologies, 28(2), 2291-2360.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-11214-1]

- Olugbenga, M. (2021). The learner centered method and their needs in teaching. International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Explorer, 1(9), 64-69.

-

Omotayo, F. O., & Haliru, A. (2020). Perception of task-technology fit of digital library among undergraduates in selected universities in Nigeria. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 46(1), 102097.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2019.102097]

-

Oyovwe-Tinuoye, G. O., & Adomi, E. E. (2021). Influence of educational qualification on job satisfaction among librarians in the university libraries of Southern Nigeria. Journal of Information Studies and Technology, 2021(1), 3.

[https://doi.org/10.5339/jist.2021.3]

-

Radez, J., Reardon, T., Creswell, C., Lawrence, P. J., Evdoka-Burton, G., & Waite, P. (2021). Why do children and adolescents (not) seek and access professional help for their mental health problems? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. European child & adolescent psychiatry, 30(2), 183-211.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-019-01469-4]

-

Rafiq, M., Batool, S. H., Ali, A. F., & Ullah, M. (2021). University libraries response to COVID-19 pandemic: A developing country perspective. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 47(1), 102280.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2020.102280]

-

Razak, A. A., Ramdan, M. R., Mahjom, N., Zabit, M. N. M., Muhammad, F., Hussin, M. Y. M., & Abdullah, N. L. (2022). Improving critical thinking skills in teaching through problem- based learning for students: A scoping review. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research, 21(2), 342-362.

[https://doi.org/10.26803/ijlter.21.2.19]

-

Roberts, K. M. (2021). Integrating feminist theory, pedagogy, and praxis into teacher education. Sage Open, 11(3), p.21582440211023120.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440211023120]

-

Robinson, H., Al-Freih, M., & Kilgore, W. (2020). Designing with care. The International Journal of Information and Learning Technology, 37(3), 99-108. doi:

[https://doi.org/10.1108/ijilt-10-2019-0098.]

-

Rose, J., & Johnson, C. W. (2020). Contextualizing reliability and validity in qualitative research: toward more rigorous and trustworthy qualitative social science in leisure research. Journal of Leisure Research, 51(4), 432-451.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.2020.1722042]

-

Rosman, M. R. M., Ismail, M. N., Masrek, M. N., Branch, K., & Campus, M. (2019). Investigating the determinant and impact of digital library engagement: a conceptual framework. Journal of Digital Information Management, 17(4), 215.

[https://doi.org/10.6025/jdim/2019/17/4/214-226]

- Safdar, M., & Idrees, H. (2021). Assessing undergraduate and postgraduate students’ information literacy skills: Scenario and requirements in Pakistan. Library Philosophy and Practice, 1A-33.

-

Salari, N., Hosseinian-Far, A., Jalali, R., Vaisi-Raygani, A., Rasoulpoor, S., Mohammadi, M., ... & Khaledi-Paveh, B. (2020). Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Globalization and health, 16, 1-11.

[https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-020-00589-w]

-

Saravanan, V., Ramachandran, M., Raja, C., & Murugan, A. (2022). Recent Trends in Blended Learning Methods. Journal on Innovations in Teaching and Learning, 1(1), 21-28.

[https://doi.org/10.46632/jitl/1/1/4]

- Sekaran, U. (2010). Research Methods for business: A skill Building Approach (5th ed.). John Wiley and Sons Publisher.

-

Soltovets, E., Chigisheva, O., & Dmitrova, A. (2020). The role of mentoring in digital literacy development of doctoral students at British universities. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 16(4).

[https://doi.org/10.29333/ejmste/117782]

-

Stein, S. K., &MacLeod, M. eds., (2023). Teaching and Learning History Online: A Guide for College Instructors. Taylor & Francis.

[https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003258414]

-

Suhirman, S., & Ghazali, I. (2022). Exploring students’ critical thinking and curiosity: a study on problem-based learning with character development and naturalist intelligence. International Journal of Essential Competencies in Education, 1(2), 95-107.

[https://doi.org/10.36312/ijece.v1i2.1317]

-

Tewell, E. (2018). The Practice and Promise of Critical Information Literacy: Academic Librarians’ Involvement in Critical Library Instruction. College & Research Libraries, 79(1). doi:

[https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.79.1.10.]

-

Torrell, M. R. (2020). That was then, this is wow: A case for critical information literacy across the curriculum. Communications in Information Literacy, 14(1).

[https://doi.org/10.15760/comminfolit.2020.14.1.9]

- Trevallion, D., & Nischang, L. C. (2021). The creativity revolution and 21 st century learning. International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change, 15(8), 1-25.

-

Uwizeye, D., Karimi, F., Thiong’o, C., Syonguvi, J., Ochieng, V., Kiroro, F., ... & Wao, H. (2022). Factors associated with research productivity in higher education institutions in Africa: a systematic review. AAS open research, 4, 26.

[https://doi.org/10.12688/aasopenres.13211.2]

-

Wagino, W., Maksum, H., Purwanto, W., Simatupang, W., Lapisa, R., & Indrawan, E. (2024). Enhancing Learning Outcomes and Student Engagement: Integrating E-Learning Innovations into Problem-Based Higher Education. International Journal of Interactive Mobile Technologies, 18(10).

[https://doi.org/10.3991/ijim.v18i10.47649]

-

Williams, S., & Kamper, E. (2023). Critical Information Literacy at the Crossroads: An Examination of Pushback from Implementation to Praxis. Journal of Information Literacy, 17(1), 232-243.

[https://doi.org/10.11645/17.1.3397]

-

Wishkoski, R., Strand, K., Sundt, A., Allred, D., & Meter, D. J. (2021). Case studies in the classroom: assessing a pilot information literacy curriculum for English composition. Reference Services Review, 49(2), 176-193.

[https://doi.org/10.1108/RSR-01-2021-0004]

-

Withorn, T., Eslami, J., Lee, H., Clarke, M., Caffrey, C., Springfield, C., Ospina, D., Andora, A., Castañeda, A., Mitchell, A., & Kimmitt, J. M. (2021). Library instruction and information literacy 2020. Reference Services Review, 49(3/4), 329-418.

[https://doi.org/10.1108/RSR-07-2021-0046]

-

Zwiers, J., & Crawford, M. (2023). Academic Conversations: Classroom Talk that Fosters Critical Thinking and Content Understandings. United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis.

[https://doi.org/10.4324/9781032680514]

James Njue Mutegi is the Head Librarian at University of Embu -Kenya. He also a PhD Student at Technical University of Kenya. His research interest focuses on Access to information, Critical Information Literacy and Information Literacy.

Dr. Lilian I Oyieke is an accomplished academic and practitioner in Library and Information Science. She is a Senior Lecturer in the School of Information and Social Studies. She has a strong background in theory, research and management of information services, resources ICTs and computer software packages (SPSS, ATLAS.ti, IN Magic, Visio, entire MS Office suite, Social Media applications, Blackboard, Question mark, Drupal, HTML, Reference Manager, Endnote). As social institutions seek to build a strengthened framework for information, Lilian’s skills are applicable in various environments. She has supervised several PhD and Master students. Her technical skills include information policy and strategy formulation, performance evaluation, knowledge management, personal information management, database management, information organization, representation and retrieval, information dissemination platforms, information literacy training, proposal writing, qualitative research methods and mixed methods research design. She has attended and presented papers at academic conferences and published articles in reputable journals

Dr. Tabitha Mbenge Ndiku is an accomplished academic and practitioner in Library and Information Science. She is a Senior Lecturer in the School of Information and Social Studies. She has a strong background in theory, research and management of information services, Tabitha Mbenge Ndiku. Her research interest includes disaster management, research methods, marketing public relation and advocacy. She has supervised several PhD and Masters students. She has attended and presented papers at academic conferences and published articles in reputable journals.